Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to write daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: Reducing the excesses of fashion

There’s not much to like about fashion, especially fast fashion. It’s bad for the planet, gets through a lot of oil-based materials, and exploits the workers, usually women, who make most of the garments. As Open Democracy reminded us last month:

“The fashion industry is at root an exploitative system based on the exploitation of a low-paid and undervalued workforce in producing countries,” according to Dominique Muller at Labour Behind the Label.

But at least the industry—certainly at the top end—seems to be feeling a bit of pressure. At least that’s what I take away from a story in Deutsche Welle about the luxury fashion house Kering buying a small stake in the second hand sellers’ platform Vestiare Collective.

Resale platforms have boomed during the pandemic while fashion houses have struggled. The reason seems to be something of a perfect storm of generational, sustainability, and economic trends, according to DW:

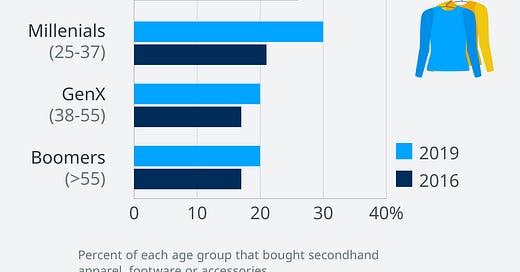

Resale platforms are particularly popular amongst millennials and Gen Z, who are thriftier and more focused on sustainability than older consumer segments… About half of millennials and mature Gen Z have experienced a decrease in income since the start of the coronavirus crisis…. The number of Millennials and Gen Z who support sustainable products more than doubled between 2019 and 2020, according to Pricewaterhouse Cooper (PwC).

If you’re going to play in the sustainability space as a luxury fashion brand, it’s better to manage the flow of garments rather than leave it to individual consumers. So one of the Kering brands, Alexander McQueen, will now take items back from customers instore, in exchange for a store credit note, and resell them on Vestiare Collective with a note of authentication.

Not that everyone is going down this road. Chanel, in contrast, has taken the resale platform The RealReal to court, claiming that its stores are the only places qualified to sell authentic Chanel. I’m not sure that’s a position that’s going to survive.

There are other business reasons for embracing resale. If you never see some customers because they can’t afford your goods, you may not see them in the future either. So there’s lots of noise in the DW piece about “recruiting the customers of tomorrow”. Well, maybe. It’s probably enough to be able to tell a sustainability story.

In that vein, Stella McCartney has debuted some fashion items made from lab-grown “Vegan mushroom leather”, although they’re not yet available to buy. More of a concept item at this stage, in other words. Mylo’s Unleather is a mycelium leather created by startup Bolt Threads. McCartney is not the only designer onboard: “Adidas, LuluLemon and the French fashion house which owns Saint Laurent, Balenciaga and Gucci, have all signed up”, according to Engadget:

The material, culled from the root system of fungi, promises to behave, and look, like animal leather, with a fraction of the environmental cost… As an animal product, leather is unsuitable for use by some religious groups, as well as vegans and vegetarians.

There are substitutes to leather, but they are all but universally produced from oil-based plastics. Meanwhile Hermes has worked with MycoWorks, using a similar approach, to producer an expensive not-leather bag.

Vogue got excited about this a couple of months ago, acknowledging the vast environmental issues associated with leather—as well as the chemicals that get poured into fashion leather so it doesn’t decompose in your cupboard. But as always, the scale of the current consumption is so huge that a bit of mushroom here and there isn’t going to make a difference. Sooner or later, we might just have to try buying less.

Britain’s churches had a day of prayer last Friday for their campaign to ‘reset the debt’ of the country’s poorest households. The campaign report (pdf) estimates that six million people in the UK have been swept into debt by the pandemic, and that low income families—especially those with children—have been much more likely to have to borrow as a result. Some are at greater risk of eviction. Effectively, those with fewest resources have had the worst effects from lockdown, while wealthier households—many of whom could continue working remotely—saw their savings increase.

The churches propose a “debt jubilee”—effectively the same mechanism that was proposed for country debt by the Jubilee 2000 campaign—which has its roots in the Old Testament. The Jubilee was a resetting of debts and obligation.

The mechanism they propose is a Jubilee Fund, a one-off scheme which would provide grants to pay off and cancel unavoidable debt accrued by households during the lockdown period. The cost of this is estimated at about £5 billion, which is not a small sum but is a drop in the ocean compared to the overall COVID-related expenditure. And it would be likely to cover a lot of its costs by reducing impacts elsewhere (homelessness, health impacts, care costs etc).

Since I was looking at debt, I also noticed a piece in the Financial Times, and in front of the paywall, that argued that everyone would be a lot better off if governments wrote off the debt that had been created through quantitative easing. The government debt held by central banks (one part of the state lending to another part) represents about $25 trillion worldwide.

Chris Watling argues that financial systems last about 40 years—two generations—before their contradictions ons become unsustainable, and we’re at that point now with our economic system. Part of his argument is that what growth we have in the system is paper gains such as house price and other asset inflation, driven by cheap mortgages, while the costs include increased inequality and an increasingly sharp generational divide.

He acknowledges that such a Jubilee would have to be done carefully. But the costs of this debt have been high:

This has created somewhat speculative economies, overly reliant on cheap money (whether mortgage debt or otherwise) that has then funded serial asset price bubbles. Whilst asset price bubbles are an ever-present feature throughout history, their size and frequency has picked up in recent decades.

Writing the debt off, in contrast, creates the opportunity for growth that is “less reliant on debt creation and more reliant on gains from productivity, global trade and innovation.”

Notes from readers. Richard Sandford wrote about the connections between Afrofutures and mark Fisher’s idea of ‘hauntology’ in his newsletter. There’s also an engaging short clip of the Afrofuturist Lonny Brooks.

j2t#066

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.