29 September 2023. Energy | Failing

The energy path on track to Net Zero // The case for intelligent failure.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open. Have a good weekend!

1: The energy path to Net Zero

Gregor MacDonald’s The Gregor Letter had a couple of useful charts in it this week, and outside of his subscription paywall.

The first one was the share of world energy production from different sources in 2012, and it looked like this:

(Source: Global Energy Share by Source 2012 | data: BP/EI Statistical Review | chart: @TheGregorLetter)

The second is the share of world energy production in 2022:

(Source: Global Energy Share by Source 2022 | data: BP/EI Statistical Review | chart: @TheGregorLetter)

You could almost be forgiven for wondering the difference is. But the main differences are that coal has lost some share, as has oil. Renewables have gained six percentage points—to 7% of global energy production.

MacDonald’s commentary is that

Coal, the energy source most vulnerable to wind and solar, lost a full three percentage points of share. And oil, which cedes ground more generally to the power system as the world electrifies, lost just a point and a half of percentage share. Renewables, mostly led by wind and solar, soared.

You can look at this two ways. The first is that the levels of fossil fuel production and consumption haven’t moved much in a decade, so what hope is there for the transition? The second is that renewables have surged since 2012 (more or less, give or take a year, the point at which they reached price parity with other energy sources), and we need to make sure they keep surging.

It’s also a reminder that energy is embedded in lots of complex socio-technical systems, often with high degrees of lock-in, and changing locked-in systems is always a difficult process. McDonald has a useful version of this: how many steps does it take to make the change?

The structural challenge that the world faces in decarbonization is that cleaning up powergrids only takes one step, but cleaning up transportation takes at least two steps, and other industrial processes require even longer... Wind and solar plug in to the existing grid. That’s pretty easy and explains their rapid growth, which is now intensifying. Transportation however requires not just that step, but electrification of vehicles. That’s partly why oil’s market share losses the past decade were only half those of coal:... oil is just a lot harder to displace.

So it was useful to also see the International Energy Agency’s update this week to its 2021 Net Zero Roadmap. It argued (I hope they’re right) that there is still, just, a window to stay below 1.5 degrees warming, and that the growth in clean energy is what is keeping it open. Since 2021, both solar installations and take-up of electric vehicles have tracked the targets inside the organisations NZE (Net Zero Emissions) model.

The IEA is an interesting organisation, in that it was created by a group of Western countries in 1974 to help to stabilise the world oil market. One of its tasks was to co-ordinate the oil reserves held by members. And this meant that when I first started doing futures, its public statements could generally be read as proxies for the view of the oil industry.

That’s not the case any longer. Under the current director, Fatih Birol, it has moved to a position where it gives a view of the energy transition that is generally not influenced by this history.

There’s always a ‘but’ to stories about energy transition, and in this case the but is that keeping open the window to staying inside 1.5 degrees involves four inter-connected steps:

Ramping up renewables, improving energy efficiency, cutting methane emissions and increasing electrification with technologies available today deliver more than 80% of the emissions reductions needed by 2030. The key actions required to bend the emissions curve sharply downwards by 2030 are well understood, most often cost effective and are taking place at an accelerating rate.

The big numbers here involve tripling the installed renewables capacity to 11,000 gigawatts by 2030, and doubling the rate of improvement in energy intensity—the amount of output you get for a given amount of energy.

Although the first target sounds demanding, the IEA says that

Renewable electricity sources, in particular solar PV and wind, are widely available, well understood, and often rapidly deployable and cost effective.

China and the richer nations are on track for this, but developing economics will need some support.

Doubling the rate of improvement of energy intensity has a significant effect. It

saves the energy equivalent of all oil consumption in road transport today, reduces emissions, boosts energy security and improves affordability.

Three actions can get us there on energy intensity:

improving the technical efficiency of equipment such as electric motors and air conditioners; switching to more efficient fuels, in particular electricity, and clean cooking solutions in low-income countries; and using energy and materials more efficiently.

The effect of these two actions together allow us to ban new approvals of unabated coal plants—which is essential to the Net Zero Roadmap plan. We also need to cut methane emissions by 75%, which we also need to do because methane is a brutal contributor to global warming, with much greater effects than carbon emissions, if much shorter lived:

Reducing methane emissions from oil and natural gas operations by 75% costs around USD 75 billion in cumulative spending to 2030, equivalent to just 2% of the net income received by the oil and gas industry in 2022. Much of this would be accompanied by net cost savings through the sale of captured methane.

One of the other notable points in the update is that it’s less dependent on technologies that are not yet on the market. In the 2021 report, these technologies were required for 50% of the emission reductions in the NZE plan. The roadmap was criticised for this at the time.

Two years on, and it says this figure has fallen to 35%. The reason is that some important technologies have come onstream in the meantime, although one of these doesn’t quite sound as if it’s on the market yet:

Progress has been rapid: for example, the first commercialisation of sodium-ion batteries was announced for 2023, and commercial-scale demonstrations of solid oxide hydrogen electrolysers are now underway.

The world will spend $1.8 trillion on installing renewables this year, but to triple capacity this figure needs to climb to $4.5 trillion by the early 2030s. It sounds like a lot, but the investment gets paid back over time through lower energy bills, because renewables are already cheaper than fossil fuels, and getting cheaper.

So part of making this happen is a business model problem: managing the upfront costs and being repaid later. The bigger problems are the need for speed—there’s no slow way to get to this—and the need for effective international co-operation.

But not doing it is worse. The IEA has a ‘Delayed Action’ scenario, which is what happens if we fall off the Net Zero path. Staying inside 1.5 degrees on that path is reliant on carbon removal technologies that, it says, “are expensive and unproven at scale”. That’s a phrase you see in reports like this which is a code for: “this won’t work.”

2: The case for intelligent failure

We are all taught these days that failure is an essential part of learning, and that we need to fail if we want to develop as people. But it’s one thing to hear that, and another thing to be able to do it. Because we have all grown up in education systems where failure is bad, and worked for organisations where failure gets punished in a whole range of less-then-explicit ways.

So it is interesting to see Amy Edmondsen writing about “intelligent failure” on the Corporate Rebels blog. She has just published a book on this theme.

We associate failure with losing. Despite the rebel appeal of failure parties, or failure resumes, it’s hard for most of us to buy into the sunny rhetoric, and the managers we work for rarely help. And yet, Nobel-winning scientists, elite athletes, and innovators in every field fail frequently. Without their failures, their successes would have been impossible. What do these resilient game changers know that most of us don’t?... How do they bounce back from the failures they experience?

The first part of this is to know that there are different kinds of failures. The set of things that are included in “intelligent failures” does not include failures that happened because you couldn’t be bothered. But it does include failures that happen as a result of complexity or bad luck.

So by working hard to prevent avoidable failures, they are able to embrace the other ones.

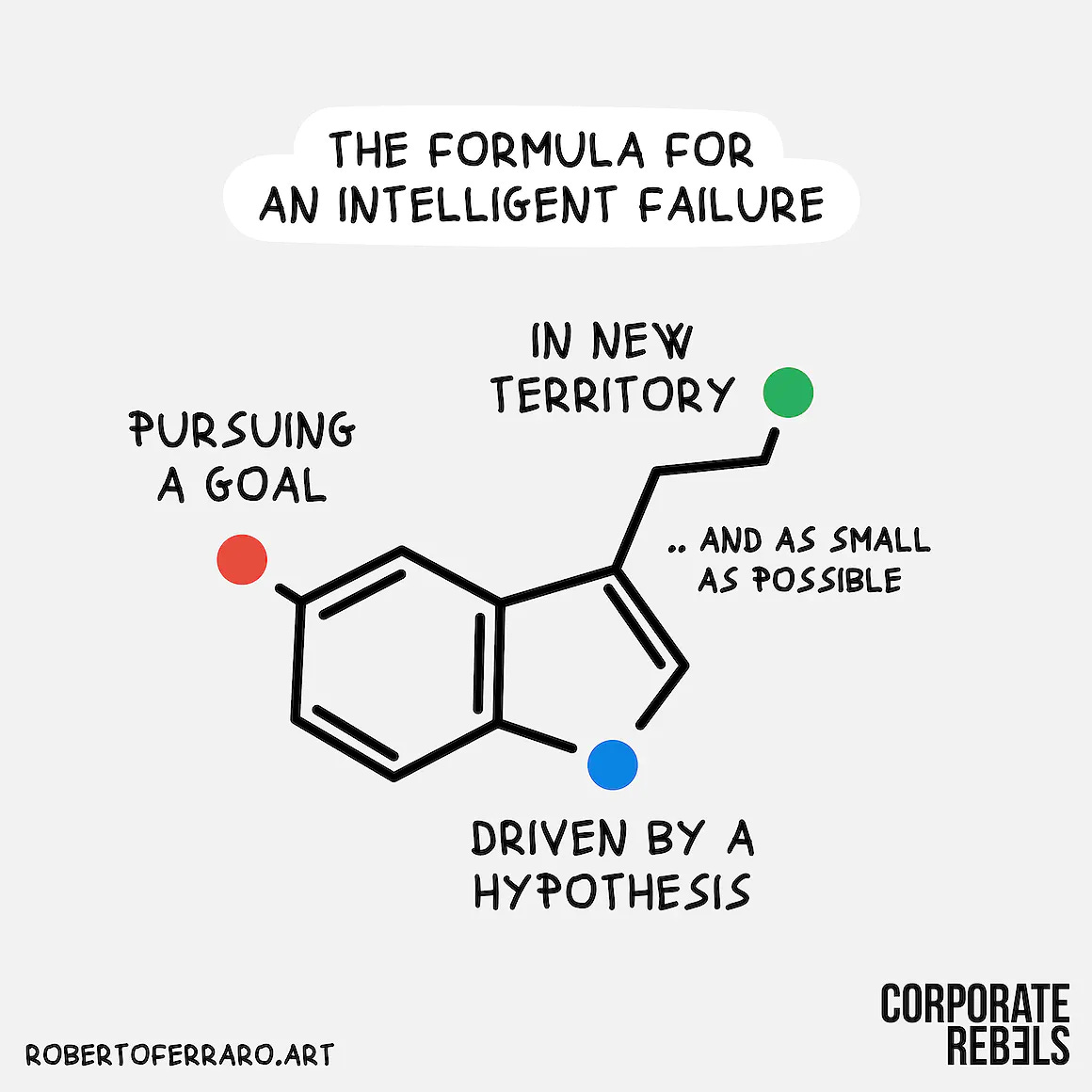

Edmondsen has developed a model from her research about intelligent failure which the Corporate Rebels turned into one of their distinctive graphics. Here are her four criteria:

It (1) takes place in new territory (2) in pursuit of a goal, (3) driven by a hypothesis, and (4) is as small as possible. Because they bring valuable new information that could not have gained in any other way, intelligent failures are praiseworthy indeed.

(Source: Corporate Rebels)

So let’s just walk through this. When you are in new territory, some failure is inevitable. If you knew what was going to happen, you wouldn’t be in new territory:

Intelligent failures, which play a vital role in expanding knowledge and achievement in every field, are, technically not preventable. Why? Because they occur in uncharted waters where there is simply no way to know in advance what will happen... When knowledge is not yet developed; you have no choice but to experiment to figure out what works (and what doesn’t).

If you never experiment you end up stagnating, which is a route, eventually, to obsolescence. Any kind of progress, any kind of adventure, comes with the risk of failure.

In the article Edmonsen writes about people who she thinks of as ‘elite failure practitioners’, which come with their own acronym (EFP):

There’s Jocelyn Bell Burnell, an astrophysicist from Northern Ireland who discovered the first radio pulsars in 1967 and James West, an African American inventor at Bell Labs (historically a haven for EFPs) who revolutionized microphones, holding more than 250 patents for his various inventions.... Or, what about Barbe-Nicole Ponsardin Clicquot, born in France in 1777 and suddenly widowed at the age of 27?

Cliquot struggled for years with both business failure and technical failure before finally revolutionising the production of champagne,

converting the originally cloudy liquid into the sparkling clear wine we know today.

Her collection of EFPs comes from different centuries and different fields of expertise. But she has noticed three things in common:

they are relentless experimenters, driven by curiosity, who’ve made friends with failure... It’s not that any of these pioneers like to fail; their understanding of its necessity drives them forward.

One of the barriers to failure—apart from a certain social stigma—is the sense that it is a waste of time and resources. Edmondsen turns this on its head:

It’s impossible to calculate the wasted time and resources created by our reluctance to take the smart risks that lead to progress.

In effect, she’s arguing that intelligent failure is a doorway to all sorts of worthwhile parts of our lives:

When we go out of our way to avoid failing, we rob ourselves of discovery, accomplishment, and meaningful relationships with colleagues... by learning to fail intelligently – in new territory, pursuing goals we care about, with thoughtful, small experiments – we can also live fuller, more adventurous lives.

If you want to know a bit more about this, or prefer to take you information in audio-visually, Amy Edmonsen was also interviewed recently at the Royal Society of Arts about her book. For some reason Substack isn’t showing this as an image, so do click on the link.The conversation runs for about an hour.

https://www.youtube.com/live/JCq0t8rynaw?si=fsP-J19QyTPoT30g

j2t#501

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.