29 November 2021. Repair | Brains

Why Apple changed its mind on the right to repair. How network theory might change the way we think about developmental disorders.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: Understanding Apple’s change of heart on repair

I’ve written a few pieces on here about the right to repair, so it’s worth noting that Apple has finally conceded that its customers should have the ability to repair Apple products. This is a big deal: of all the tech companies Apple has been noisiest in insisting that it was absolutely impossible to have people repair their own Apple products.

Cory Doctorow has taken stock of the moment.

Much of it is down to the change in the legal and regulatory mood around repair:

First came the Massachusetts Right to Repair ballot initiative, then the New York Right to Repair bill, then the FTC’s Right to Repair enforcement order, and the President’s Executive Order on competition, which took a strong stance on right to repair.

But part of it was pressure from customers and stakeholders, who made it harder for Apple to maintain the pretence that repairing its products was impossible:

Apple’s stakeholders were increasingly and vocally disappointed with the company’s stance on repair. Everyone from Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak to its shareholders to its own employees had called the company out on its repair stance.

Even though Apple shareholders had tabled a motion on repair, which might have ended up going to the Securities and Exchange Commission, the company’s announcement still took people by surprise. Although the announcement was accompanied with some media chat about having been working on the initiative for a year, companies are always full of initiatives that people work on just in case, and which never see the light of the day.

(iPhone 6s that have seen better days. Photo, Thilo Parg, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Doctorow speculates that there’s been a split within the company between hard-liners who were willing to die on the hill of never allowing repair, and those who thought that repair was the right thing to do, both environmentally and for customers, and would also be good for the company’s image and reputation.

Changes in the external environment, therefore, changed the balance of power:

Some combination of the looming threat of regulatory enforcement, legislation, shareholder battles, publicity bloodbaths, and angry employees in a fiercely competitive job environment tipped the balance of power to the pro-repair faction within the company.

Suddenly, the cost of allowing repair to the business was less than not allowing it.

But of course, there are repair programmes and repair programmes. Apple has form here; its ‘independent repair programme’ launched in 2019 that critics labelled as ‘repair theatre’:

Shops that signed up for it found themselves forced to sign onerous NDAs and were subjected to impossible conditions. For example, IRP repair shops were banned from holding inventory of common parts like batteries or screens. Instead, they were required to gather invasive customer data on anyone who showed up looking for a repair, submit that data to Apple, wait for it to be processed and approved, and only then would Apple send the part. The customer, meanwhile, was deprived of their phone or laptop while they waited for this rigamarole to run its course.

This time around, there are organisations out there monitoring what a good repair programme would look like. Ifixit has produced a checklist. It might have to drop its warranty conditions about self-repair as a starter.

But as Doctorow observes, it’s not just Apple that are hostile to repair. In the piece, he calls out the US shaver repair company Wahl, and John Deere, the notorious tractor business.

And although we do need effective regulation and legislation to enforce the right to repair as a public and consumer right, one of the interesting things about the current moment is that pro-environmental shareholders have started to focus on repair as a meaningful issue.

Microsoft folded its opposition to repair in the face of a right-to-repair resolution brought by an environmental nonprofit, As You Sow.

The resolution asked Microsoft to study the environmental and social benefits of increasing access to repair; Microsoft not only agreed to conduct such a study but to act on the findings by the end of 2022.

John Deere is now in the firing line from activist shareholder motions as well. They won’t be the last, I suspect.

#2: How network theory might help us understand some developmental disorders

A guest post by Peter Curry

Peter Curry has a long post on his newsletter on how thinking about network theory may be improving our understanding of development disorders such as ADHD, Asbergers, etc. His post starts with an explanation of some introductory network theory—so best to read the whole post there if you need that refresher.

One of the important insights of scale-free networks is that real networks don’t connect randomly. So, when you add in new lines, they usually connect to the most connected dots (or nodes). The implication of this work is that we usually don’t see the random networks as much in the real world, and instead, we’re better off modelling using scale-free networks.2

By now you’re probably thinking, looking at dots is tons of fun, but what’s the point of all this? The answer is that we can get a lot of insight into how things work using these sorts of methods. The other answer is that things in themselves often have a certain set of properties, but once they’re connected to other things, a totally different set of properties emerge.

I use the nonspecific ‘things’ intentionally, because nearly every conceivable thing can be modelled as a network if you really want to do so. Classic examples include traffic systems, Facebook friends, and that time Charlie from Sunny got to the bottom of the mailroom conspiracy.

Network Neuroscience

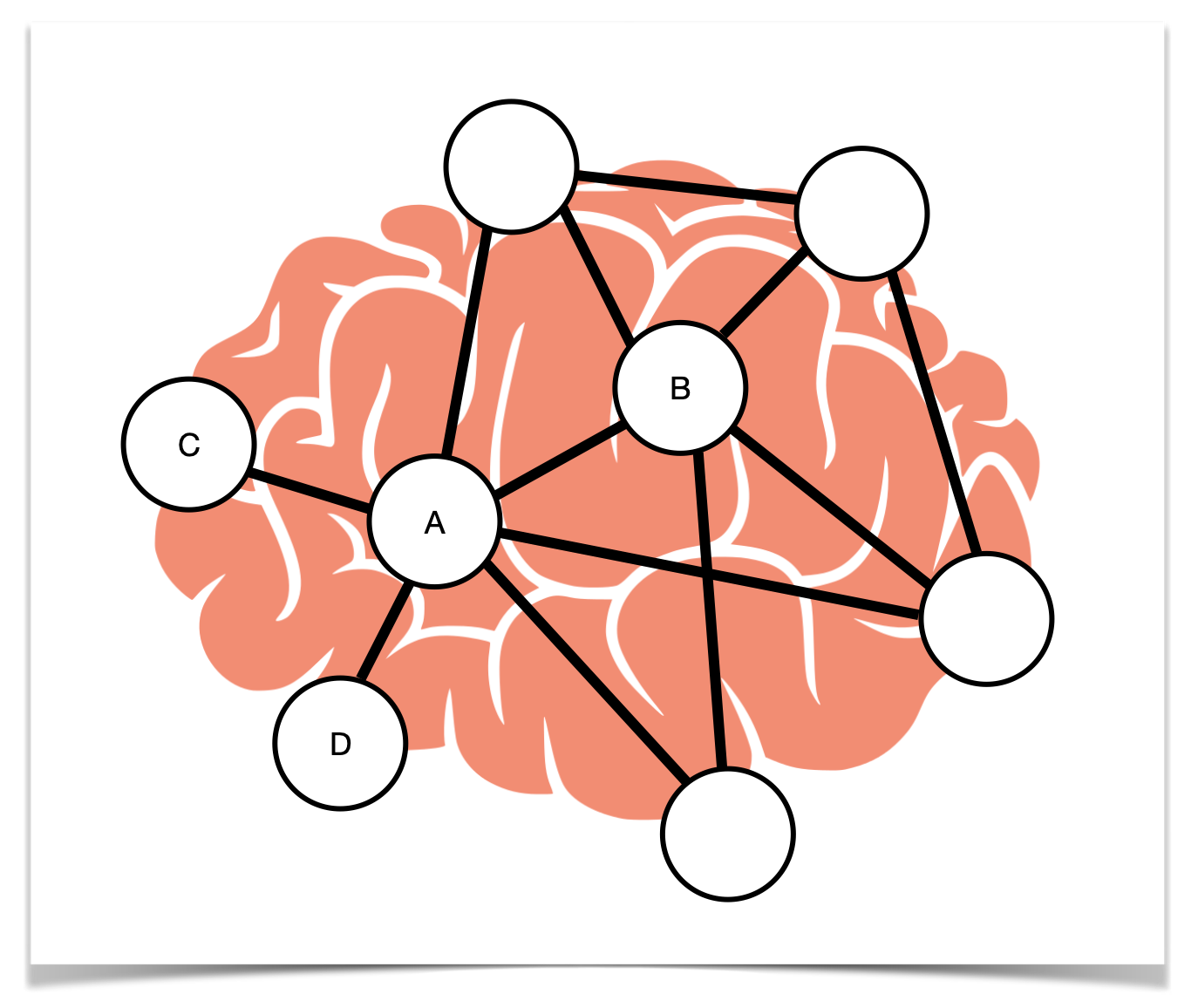

If we apply these principles to brains, all sorts of interesting things happen. Firstly, let’s turn our nice scale-free network into a brain network by adding a picture of a brain behind it:

Great. So, one of the problems with developmental disorders like Autism Spectrum Disorder, or ADHD, or Aspergers, is that diagnoses are pretty variable. There seems to be a common set of symptoms, but the actual pathology is hard to pin down.

Siugzdaite et al. (2020) suggest that one of the main reasons for the difficulty tying symptomatology to pathology might be due to the way that brains networks are connected to each other.

They ran a huge study with 479 children (the average neuroscience sample size varies from around 20-30), and used a series of computational models to interpret the data.

They found that connectivity of different brain nodes and hubs was most predictive of whether children had developmental disorders. Kids with developmental disorders tended to have more distributed connections, with weaker hubs, while those without tended to have scale-free structures; networks with large, centralised hubs that dictate traffic.

As far as I can tell, Siugzdaite and friends are not specific on what these hubs actually represent, but Olaf Sporns has an answer here:

Several structural network studies of the human cerebral cortex have converged on a restricted set of regions that include the precuneus, anterior and posterior cingulate cortex, insula and portions of the superior frontal, temporal and lateral parietal cortex as putative network hubs.

The way they found this out was by running ‘attacks’ on the network, by disabling hubs at random (in a computer model, not in the children themselves, bloody ethics committees etc. etc.). For instance, imagine if we took out A in the brain network above. C & D are now unreachable, and left to fend for themselves.

In the counter-example, look at our random network:

Disabling A here is annoying, but we can still get everywhere. It’s just more circuitous. So the researchers were able to determine that there were different brain architectures because disabling hubs has a massive impact on children with highly efficient, hub-driven networks, but much less of an impact on children with more distributed networks.

But look at the structure of both brain networks! If the hubs are working, then the first network is much more efficient than the second one. It’s easier and faster to get around.

Siugzdaite clarifies this point:

The more central the hubs to a child’s brain organization, the milder or more specific the cognitive impairments. By contrast, where these hubs were less well embedded, children showed the more severe cognitive symptoms and learning difficulties.

So what does that mean more generally? Well, it suggests that any specific developmental diagnosis is less important than trying to determine the overall brain connectivity. To take a hypothetical, a child with autism and a child with Aspergers may have the same underlying brain structure, but a different connectivity map between different nodes. The emergent structure of this connectivity then generates two different sets of behaviour, resulting in the different diagnoses.

This study isn’t perfect by any means, and there’s a good review of it by Michael Thomas.

It also suffers from the usual neuroscience problem, which I’m going to call ‘WTFCATS?’ or ‘What the fuck causes all this shit?’ (In practice, many prominent brain imaging techniques are notoriously bad for determining causation.)

Here’s Siugzdaite to elaborate:

Do local differences cause this greater integration to develop as a means of dynamic compensation over developmental time, or, does this integration vary across children regardless, making some more susceptible to the ongoing underdevelopment of specific regions?

All of this stuff can hopefully be tested (both Siugzdaite and Thomas think a similar longitudinal study would resolve a lot of questions), and network theories of systems are invaluable for getting towards understanding all manner of complicated problems.

With a better understanding of how the brain organises itself, we might be able to intervene and nudge those with developmental disorders towards a better brain architecture.

j2t#216

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.