Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to write daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story

#1: A turning point for climate change?

I know that it’s ridiculous to be even slightly optimistic about climate change. We still look as if we’re heading for two degrees warming, with all that that means for climate induced catastrophe. But that is the thrust of a long and frankly must-read article by David Wallace-Wells in New York magazine.

Wallace-Wells wrote the New York article “The Uninhabitable Earth” about climate change in 2017, which became a grim book of the same name in 2019, so it means something that he’s seeing some glimmerings of hope now. And he does put this into perspective early on:

A turning point isn’t an endgame, or a victory, or a cessation of the need to struggle — for speedier decarbonization, for a sturdier future, for climate justice. Already, a future without profound climate suffering has been almost certainly foreclosed by decades of inaction.

I’m not going to try to summarise his latest article, but he gives a few grounds for optimism that we might at least have hit a turning point.

The first is that we have seen a torrent of announcements from countries across the globe: UK, Italy, Canada, Denmark, Japan, South Korea, and, perhaps most significantly, China, have all announced significant decarbonisation commitments. There are others as well. Biden’s position on climate change notably hardened during his campaign.

Second: the age of climate denial is over. Obviously, visibly, in the US, but more widely this has been one of the stories of 2020. Partly that’s down to extreme weather, partly down to the work of a wide range of activists, but there have been other signs as well. Exxon, for example, has fallen out of the Dow Jones Industrial Average: “The cultural cachet of oil companies is quickly approaching that of tobacco companies.”

Image: WWF

Third: we have reached the point of climate self-interest. Until recently, dealing with climate change was regarded as too expensive (as people queued up to tell Nick Stern in 2006, despite the story he laid out then to the contrary). Now it’s too good a deal to miss out on. Wallace-Wells notes a recent McKinsey report along these lines. There is, he says, “growing consensus in almost every part of the globe, and at almost every level of society and governance, that the world will be made better through decarbonization.”

Actually, there’s more to this. We’ve spent years wrestling with climate change as a collective action problem, and hence the endless COP meetings. But most of the progress and commitments of the past year have been made outside of the shared agreements. And research by Matto Mildenberger and Michaël Alkin “found that, despite much consternation about designing climate policy to prevent countries from “cheating,” there was basically no evidence of any country ever pulling back from mitigation efforts to take a free ride on the good-faith efforts of others.” There’s not a collective action problem after all.

Finally—and this is strictly relative—while we’re certain to hit 1.5 degrees (we run out of carbon budget on that in just seven years) we’ve got longer to avoid two degrees—assuming, that is, that some of the negative feedback loops don’t kick in.

And this is against a background of rapidly falling prices for solar, batteries, and so on.

Of course, the gap between what we should be doing, and what we are doing, is still growing. Although the relevant curves are now bending in the right direction, they’re not bending fast enough. A two degree world is still an ugly outcome:

It won’t be enough. It can’t be, because we are too far along. There is no solution to global warming, no going back. Achieving a two-degree goal, by rates of decarbonization only dreamed of a decade ago, would deliver a world that looked then quite unforgivably brutal…African diplomats have wept at climate conferences at what it would mean for the fate of their continent, calling it “certain death”; island nations have called it “genocide.”

Anyway: well worth taking the time to read it.

#2: “Making the future visible”

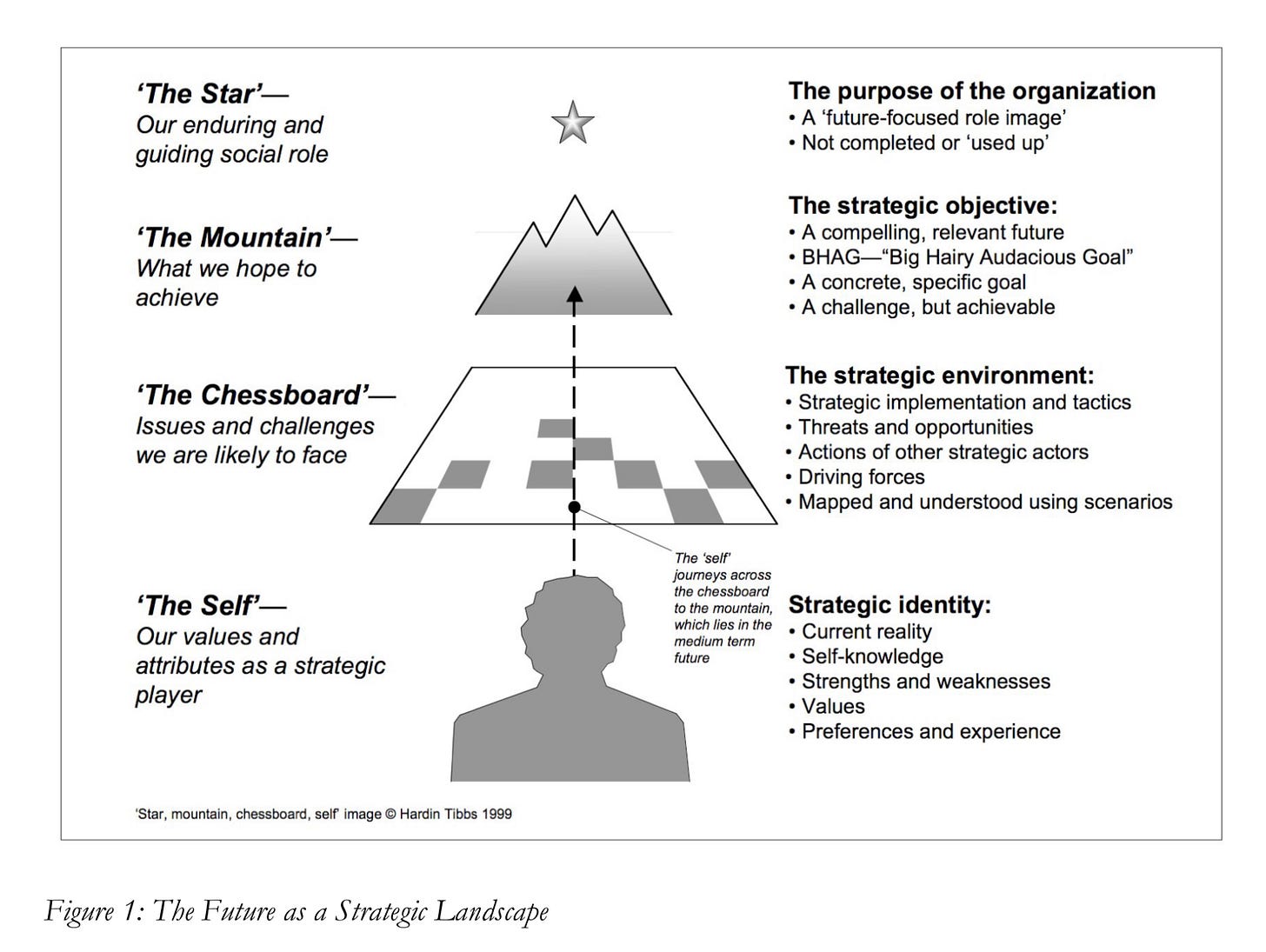

Hardin Tibbs’s 1999 paper “Making The Future Visible” is a bit of a cult classic among futurists. It was published only on his own website as a working paper, but it is relatively widely used now. The reason for this is because the underlying model he proposed in it connects different aspects of futures work that are often disconnected: vision, possible futures or scenarios; and strategy or action. The model — star, mountain, chessboard, self — is shown in Hardin’s diagram here.

Anyway, the reason this is relevant now is that I am guest-editing a special edition of World Futures Review with reflections on the original paper. It will include an interview with Sohail Inayatullah and a 20-years on reflection by Hardin. Although that’s not quite ready yet, WFR has just released an online version of my introductory article, which should be open access. Here’s an extract:

Its [1999] date is important: it comes at the end of a decade when almost all of the intellectual energy in futures work had been around scenarios work, and the commercial energy had been dominated by the 2 × 2 double uncertainty scenarios method... The futures landscape proposed by Tibbs in his paper challenges much of this thinking. It is made up of four elements, which combine external and internal perspectives. Together, he writes, they represent “the psychological reality of the future by giving equal weight to anticipation and aspiration.”

Hardin’s original paper is here (pdf).

J2t#019

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.