28 March 2023. Inflation | Mothers

Welcome to the ‘profit-price spiral’. // We need a ‘politics of mothers’.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

Apologies to have missed a couple of recent editions. Pressure of work, and all that.

1: Inflation’s new ‘profit-price spiral’

If you haven’t noticed, there’s something of a financial crisis going on. In California, depositors in Silicon Valley Bank had their funds guaranteed by the US Federal Reserve Bank — unusually, the bank wasn’t bailed out, but the customers were, which probably says something about the ability of Silicon Valley to make up a story about its systemic importance, even in these dog days of the long digital technology surge. Another three banks have also gone bust in the US, although one was rescued by JP Morgan and Goldman Sachs.

And in Switzerland, Credit Suisse has been sold to UBS for a knockdown price (admittedly of $3.25 billion) in a takeover orchestrated by the Swiss National Bank to stop it going bust. When I say ‘orchestrated’:

The Swiss state’s offer of a lifeline to the hastily merged new private, global mega-bank took the form of an explicit guarantee of 100 billion Swiss francs ($109 billion).

That quote comes from a post by the economist Ann Pettifor this week, which argues, basically, that these failures have come from the determination of central bankers to keep hiking up rate rises.

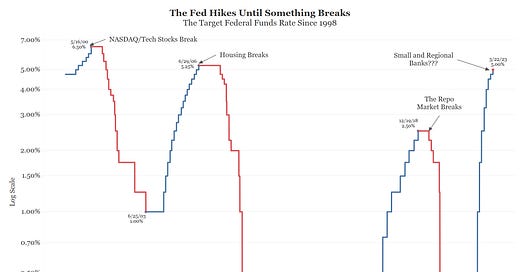

She quotes the analyst Jim Bianco, who posted a series of tweets to the effect that “the Fed hikes until something breaks’ with a striking chart going back over the last 25 years. Things that have been broken here include tech stocks in 2002 and the housing market in 2008.

Of course, the only people who are suggesting that our economic and financial problems might not be solved by pushing up interest rates tend to be radical economists or dissident investors. All the same, it is worth asking why this is happening.

In a different article, Ann Pettifor suggested that it was a form of class warfare in which wages needed to be suppressed to get inflation under control, and that the banking system was collateral damage. (The metaphor may not be quite right. It may just have been hit by friendly fire).

There’s another view of this, which is that central bankers are so locked into a view of the last inflationary crisis, which was at least partly driven by wage rises, that they haven’t noticed that this time around the forces driving inflation are completely different.

In the New Statesman, another radical economist, James Meadway, tells this story:

the inflation we are experiencing is unlikely to be tamed by interest rate increases, because price rises are flowing from a lethal combination of global instability and profit-maximising monopolies. We are being marched into an economic polycrisis of financial failure, soaring inflation and recession.

Of course, central bankers are myth-makers too, and they spent the 1990s and most of the 2000s telling anyone who would listen that the reason we had a long period of low inflation and low interest rates was because central bankers now had a very sophisticated understanding of all of the macro-economic and monetary tools at their disposal. A narrative needs a name if it is going to stick, and the head of the US Fed, Ben Bernanke, came up with one: ‘the Great Moderation’.

That ended well, of course. Meadway suggests another explanation for that period of low inflation:

a far more plausible cause of prolonged low inflation was the massive decline in the real price of manufactured goods as eastern Europe and, especially, China were opened up to global markets. Four hundred million formerly agricultural residents moving into China’s booming industrial cities and factories had more impact than a decade’s worth of “independent” chin-scratching by the (Bank of England’s) Monetary Policy Committee.

Meadway has just co-written a short book on the current crisis, and he and his co-authors argue that the current inflation has nothing to do with wages:

the inflation we are experiencing is unlikely to be tamed by interest rate increases, because price rises are flowing from a lethal combination of global instability and profit-maximising monopolies.

Looking back at the years since the financial crisis, and the vast amount of quantitative easing underwritten by the Bank of England, there’s been little relationship between the rate of inflation and Bank of England policy, even if quantitative easing did inflate assets hugely and transfer lots of wealth to the already wealthy.

Undeterred, the Bank of England has increased interest rates again last week. The theory here is ugly.

It hinges on higher borrowing costs and more attractive savings rates, inducing less spending and so raising unemployment which, in turn, disciplines workers, frightened by the prospect of joblessness, into accepting lower pay rises. Lower pay is then expected to feed into lower prices overall.

But when wage increases are way below inflation, the theory is plain wrong. So it’s worth unpacking that line above about ‘global instability’ and ‘profit-maximising monopolies’.

The global instability part is pretty familiar:

The global factors are obvious: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine; the lingering impact of supply chain disruptions from lockdown; and, increasingly, a more unstable global environment that is raising the costs and difficulties of production.

The bit of the profit-maximising monopolies tends to leak out at the edges, and not usually in mainstream economic coverage (but journalists are mostly illiterate about economics).

the explosion in large corporate profits over the past year has been exceptional. The extreme profits of the energy companies, made just as energy bills surged, are well known. But profits for food giants have also soared, with the four largest global agribusinesses seeing profits rise by 255 per cent since the Covid-19 pandemic... Profit margins for the 350 largest companies on the London stock exchange were 89 per cent higher this year than before the pandemic.

In fact the only person who has managed to make this point consistently in British media over the last year was the rail union leader Mick Lynch, while defending his members’ pay claim.

So this isn’t the ‘wage-price spiral’ that seems to have gripped the imagination of central bankers, and gets parroted by conservative politicians, for more obvious reasons.

This is more like a ‘profit-price spiral’, and Meadway points to a new paper by two American economists, Isabella Weber and Evan Wasner, which makes this point. The title: “Sellers’ Inflation, Profits and Conflict: Why can Large Firms Hike Prices in an Emergency?”(It’s publicly available).

The model they suggest in the abstract goes like this:

(1) Rising prices in systemically significant upstream sectors due to commodity market dynamics or bottlenecks create windfall profits and provide an impulse for further price hikes.

(2) To protect profit margins from rising costs, downstream sectors propagate, or in cases of temporary monopolies due to bottlenecks, amplify price pressures.

(3) Labor responds by trying to fend off real wage declines in the conflict stage.

They argue that what policy-makers need to do is to intervene at the ‘impulse’ stage, or stage 1, and the word ‘windfall’ might be a clue here.

Meadway suggests that we need selective price controls on some key commodities, such as natural gas, that prevents such, well, profiteering, and that we need to weaken the grip of large corporations on “essential supplies”. He thinks we need to do this by creating alternatives, and I don’t disagree with this. But effective competition policy that set out to reverse the domination of our economies by a small number of giant corporations would also help. Because there’s clearly ‘consumer harm’ here.

2: We need a ‘politics of mothers’

There’s a short piece by Victoria Smith that says that we need a ‘politics of mothers’. The way that’s phrased it would be easy to misunderstand her purpose, especially in The Critic, which enjoys being contrary, but this is, to be clear, a call for a feminist politics of mothers.

She starts the piece with a quotation from the writer Rachel Cusk:

What do I understand by the term “female”? A false thing: a repository of the cosmetic, a world of scented boutiques and tissue-wrapped purchases, of fake eyelashes, French unguents, powder and paint… What it once meant to be a woman, if such a meaning can ever be fixed, it no longer means; and yet in one, great sense, the sense of procreation, it means it still. The biological destiny of women remains standing amidst the ruins of their inequality.

There’s a nod to Mary Harrington, whose recent book Feminism Against Progress argues that “sex denialism holds a particular attraction for the most privileged women, at least until the realities of pregnancy, birth and motherhood hit home.”

Image by Viewminder/Flickr. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

One of the effects of the current economic crisis is that some of the anger of mothers has become newsworthy—newsworthy enough that politicians (some of them recent mothers themselves) have tried to capitalise on it. Smith hopes that something comes from this. But:

Even so, I can’t help thinking that one of the reasons progress is so slow comes from a lack of foresight. So many of the voices raised today are the voices of women who didn’t see it coming. They would have — we would have — if only we’d been brave enough to see the connections we have with the mothers who went before us.

A lot of the discourse of equality has been about eliding differences between women and men. I’d observe here that this has been a necessary step, since otherwise men would still be claiming that they had special characteristics that women would never be able to match (look at any of the early 20th century arguments against women getting the vote for examples of this.)

But the other half of this is that motherhood is one of the largest single causes of economic inequality between women and men, since women who leave the workforce to have children never completely recover their earning power.

The detachment of femaleness from motherhood therefore sits in power structures that are still dominated by men, and which devalue women.

(This devaluation) is also helped along by a refusal to recognise the importance of female bodies and life cycles, on the basis that such recognition is far too restrictive, exclusionary and uncool... By dividing women, and by bolstering the myth that motherhood has nothing in particular to do with femaleness, and vice versa, it sets each generation of women up for a fall.

Smith also notes that Oxfam has recently decided to stop referring to ‘mothers’ and instead talk about ‘parents’, because it doesn’t want to reinforce existing gender roles. Smith is, rightly, scathing:

Almost half a century since (Adrienne) Rich painstakingly distinguished between motherhood as experience and as institution, along comes Oxfam to tell us that the exploitation of mothers isn’t down to a failure to differentiate between their specifically female experiences and the low status imposed on them. It’s literally down to their being called “mothers” rather than “parents”. One might find it remarkable that no one thought of this before.

And she is not optimistic that politicians such as Stella Creasey, who have started talking about the issues that mothers face, will make much of a difference—precisely because they don’t seem concerned about the erasure of language here:

It is necessary to be specific when talking about the politics of parenthood — especially should one wish to make it a feminist issue. Parents do not experience pregnancy discrimination; parents do not see a fall in relative income upon having their first child; parents do not need specific accommodations for breastfeeding and postpartum care. Mothers do.

The point in the naming, she says, is to be clear about who is exploiting whom, and to start disentangling those “roles which are related to reproductive difference and which are not”:

If we want a truly radical political deal for mothers, we need to respect them. We do not respect people whose very right to name themselves is withdrawn. Nor do we allow mothers to recognise the things they share with other women — those who are not yet mothers, those who might never be — when we sever the link between maternity and femaleness.

j2t#439

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.