29 March 2022. Drugs | Politics

Psychedelics? The start-ups are high already. Measuring right-wing extremism.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

1: Psychedelics? The start-ups are high already.

Making a more conventional market in drugs is a good thing—we can all be pretty confident that the century-long experiment in criminalising drugs hasn’t worked—along with performative nonsense about ‘drugs tsars’ and ‘wars on drugs.’

But when decriminalisation comes business interests are close behind. A long long cover story in The Nation by Zoe Cormier is headlined, ‘The Brave New World of Legalized Psychedelics Is Already Here—And so are the profiteers. Get ready for Psychedelics Inc.’

The paradox of this market at the moment is that making psychedelics can still land you in jail, certainly in the United States, which the article focuses on. But marketing them gets you friendly meetings with venture capitalists:

More than 50 publicly traded companies working to develop or administer psychedelic compounds are now operating in America—three of them already valued at over $1 billion each: Angermayer’s ATAI Life Sciences, Compass Pathways, and GH Research. By some estimates, the industry is projected to soar from $2 billion in 2020 to $10.75 billion by 2027—which would be an even faster rate of growth than that of the cannabis market. Hence the trading floor shorthand for psilocybin: “the next marijuana.”

Psychedelics have a long, long history, going back hundreds of years into indigenous histories. They were made illegal quite late on during the various moral panics about drugs, even after researchers and even the CIA had experimented with them. As Cormier notes, the Swiss company Sandoz, which manufactured them in the 1940s and afterwards, gave them away to American psychiatrists for research purposes. Nothing says ‘counter-culture’ quite like a psychedelic drug.

(Bridget Riley, cataract 3. Liverpool Art Gallery. Photo by Terry Kearney/flickr. CC0 1.0 Public domain.)

Scientists researching in the area worry that with Big Pharma’s new-found interest will bring a whole lot of business practices that are good for their business but bad for research. And—in tracking the long post-war history of LSD, Cormier also notes that it is science that has got us to the point that psychedelics might be legalised, by identifying benefits from them. In particular, they seem to be effective in dealing with depression, one of our more widespread mental illnesses (and possibly one of the more intractable) of our times. (I think Oliver James once described depression as “America’s biggest export”, but I can’t trace the quote right now.)

Credible research studies have been published in leading scientific and medical journals. There is bipartisan support in the US Congress that it’s OK to treat veterans with MDMA. In the US several jurisdictions have already voted to decriminalise psylocybin:

The Food and Drug Administration granted “breakthrough status” to psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for “treatment resistant depression” in 2018, thus recognizing the treatment as a “substantial improvement” over conventional therapies. By treating depression with a completely new mechanism of action, psilocybin-assisted therapy has changed the playing field—and thus will be sped through regulatory hurdles for further study and eventual approval. MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD has received the same status.

Hence the commercial excitement. Well, it’s a long article, even sprawling, and it corrals together some unusual bedfellows, from Mike Tyson to Peter Thiel to Amanda Feilding, the Countess of Wemyss and March.

Thiel, inevitably, is an investor in one of these businesses, and I was slightly surprised to learn that the British drugs scientist David Nutt (I wrote about a talk he gave on cannabis here) was an adviser to Compass Pathways, one of the two psychedelics companies that Thiel had invested in.

Nutt’s generally one of the good guys in this whole discussion, and his position is simple enough:

“Most of the people who will benefit from our research will never even have heard of Peter Thiel—they want a medicine that will help them when other medicines won’t. If, at present, the only way to get that medicine is through a for-profit company, then that is how it has to be. Maybe it’s not ideal, but we spent 50 years doing nothing, and it’s time we did something.”

At the same time he’s concerned that the companies wading into this space are people with no background in it or knowledge of it. (What could possibly go wrong, after all?) At the same time, as Nutt observes, there are also benefits in having Big Pharma involved:

”(A)t least we would have good quality control on the compounds.”

But Big Pharma is as Big Pharma does—and so we’re already seeing patent wars around the possible construction of psychedelic compounds.

In theory, patents provide an incentive to innovate. In reality, they often incentivize companies to concoct dubious excuses for laying exclusive claim to something they plainly didn’t invent. For instance, psilocybin, mescaline, and DMT are all found in nature—DMT is even found in the human body. None of them can be patented, and the patents on LSD’s chemical makeup expired in 1963. But a tiny modification... to the molecular makeup of each is enough in the eyes of a patent office lawyer to stake a claim, even though new analogs rarely have new effects.

But—it’s possible that the commercial prospects for psilocybin have been overstated. The publication of one of the research studies mentioned above, in the New England Journal of Medicine—saw the value of some of the start-ups fall. The reason is that the results of psychedelics were good, but they were no better than those of the control group, which received the more conventional SSRI drug escitalopram.

More to the point, both groups received 40 hours of therapy, which the researchers thought might be the main reason for the improvement. The psychedelics help make the therapeutic relationships work better. But although this might be bad news for the psychedelics start-ups, it suggests that we’re still likely to see bad things happen:

(The start-ups) seem totally unprepared to deal with some of the challenges that psychedelics can present. Unlike with an SSRI or an antibiotic, the effects of psychedelics are unpredictable—a person can become angry, weepy, or, of course, psychotic. Without preparing adequately for bad trips and much worse, things could get very ugly for many of these inexperienced start-ups.

“Psychedelic therapy is not scalable by definition,” says Dr. Jack Allocca, a pharmacologist. “Injecting it into a scaled model, that of traditional capitalistic product development, in the long term is a death sentence…. Eventually, something truly catastrophic will happen—and somebody will have to pay the consequences.”

2: Measuring right-wing extremism

At his Understanding Society blog, Dan Little proposes that we need an extremism index to assess whether people elected to public office are fit for it.

He suggests seven behaviours that it might include:

- justifying or encouraging political violence

- condoning racism and white supremacy

- vilifying their political opponents

- aligning themselves with openly insurrectionary organizations

- expressing admiration for authoritarian leaders in other countries

- calling for extreme voter suppression legislation in their home states

- defending the January 6 rioters as "peaceful protesters".

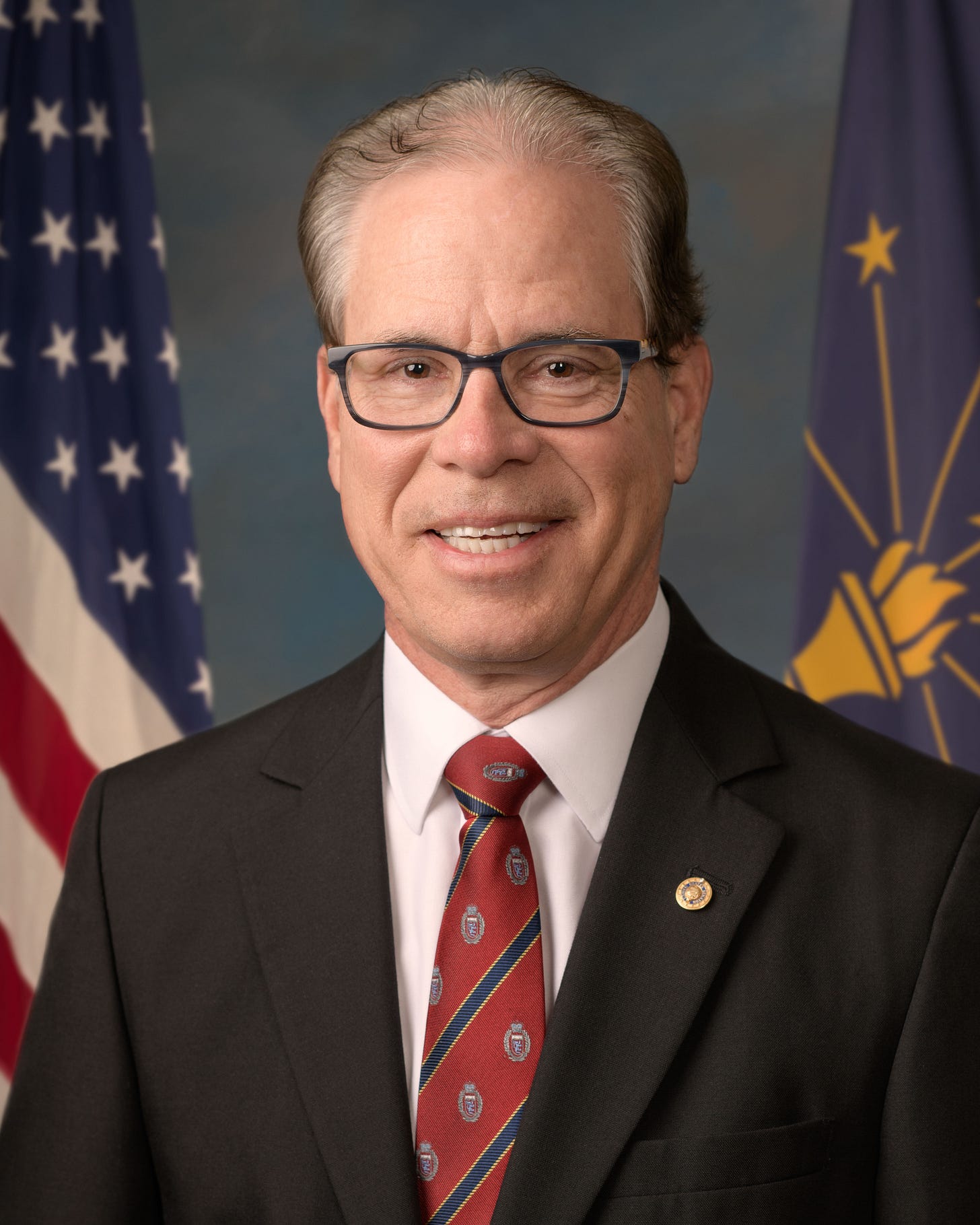

What prompted this suggestion is a remark by Republican Senator Mike Braun:

(He) Senator Mike Braun (R-Indiana) made news in the past few days by questioning whether the Supreme Court was right to rule in 1967 that state bans on interracial marriage were unconstitutional.

—

(Senator Mike Braun. Photo, United States Senate Photographic Studio. Public domain).

Little sees the index as a research method to attempt

a more systematic study of the extent and depth of anti-democratic rhetoric among our elected officials based on their public speeches and comments.

As he says, this could be a big data project, drawing on textual analysis of speeches and interviews, and no doubt social media content. News organisations might be interested in publishing it.

There would likely be some individuals who spiked high only on one or two of these behaviours, others who managed to correlate heavily against five or six.

His hope is that by making this more visible, rather than lost in the continuous noise of rolling news,

as citizens we would be in a much better position to understand the depth and breadth of the threat to democracy that we currently face. And it is likely that many of us would be jolted and alarmed at how long those lists are.

I have serious doubts about this. In the current completely polarised political climate of the United States one could easily imagine Republican representatives and their political base ratcheting it up rather than backtracking. We saw something similar happen in the UK with boardroom pay where greater transparency produced status competition and an upward spiral, rather than shame about pay ratios.

And I can’t even start to say how profoundly uncomfortable I was writing this up, as I thought about the implications. In a world in which we have seen death threats against left-wing minority women members of the House of Representatives, it pushes America even further into forms of McCarthyite discourse that is likely to accelerate violence.

But perhaps this is just another sign that American democracy has already gone past the brink.

j2t#289

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.