28 February 2022. Clothes | Protest

The brutal history of clothing. Remembering Sofie Scholl and The White Rose.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

1: The brutal history of clothing

I came across accounts of Sofi Thanhauser’s book Worn slightly by accident—it was published in January, and is a history of clothing, built up from chapters about different types of material.

The review in Literary Review opens with this observation:

(T)oday it is more expensive to make your own clothes than to buy them. This is a relatively recent and shocking development in the history of human dress. How did such a situation come to pass?

Thanhauser’s book attempts to answer this question, taking a long view of the history of the clothing industry. The short-run answer to the question is four decades of globalisation, pressure on wages in the global South, and cheap logistics and shipping.

But she takes a longer view as well, going into the long history of clothing, and visiting different parts of the world to learn more. As Shahdida Bari says in her review, Thanhauser is also interested in how clothes are made:

Where others have been seduced by the ecological grandstanding of big fashion houses and earnest designers, Thanhauser’s interests are always concentrated on the local, the labourers and the makers.

Some of the early material is obviously selective, but clothing seems to have had an important part in the early history of the species:

Clothing, she speculates, was the technology that enabled the first humans to leave Africa and confront the conditions of the Ice Age. Since cloth perishes, it’s difficult to identify its earliest use, but researchers using the DNA of lice have determined that humans probably began clothing themselves in hides and pelts 170,000 years ago.

And of course, there’s a gendered history here as well:

Making, she writes, was women’s work because it was ‘compatible with child-rearing’. Yet women were long deprived of their ‘right to conduct economic activity’, through, for instance, the establishment of male-only professional guilds. Isaac Singer, one of the inventors of the sewing machine, eventually declared it a ‘devilish machine’, rueing how it did away ‘with the only thing that keeps women quiet, their sewing’. Thanhauser, on the other hand, recognises what a radical invention it was: a machine dedicated to the performance of domestic rather than industrial labour.

The production and use of cotton, in particular, has been brutally destructive. It plays a central part in the slave trade, requires the aggressive use of chemicals or herbicides, and is the reason that the Aral Sea has all but dried out. (Sven Beckert’s book The Empire of Cotton has more on this. Much more.) A review in the Washington Post spells out the embodied water that goes into making cotton clothes, quoting Thanhauser:

“twenty thousand liters of water to make a pair of jeans, enough to grow the wheat a person would need to bake a loaf of bread each week for a year.”

And the Washington Post reviewer conveys a sense of the way in which fabric, fashion, and economic power have been intertwined for several hundred years now:

We read of similar connections between the fortunes of linen and women’s rights in the workplace; between the decline of Chinese silk and the rise, by way of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, of mass fashion; and between the introduction of synthetic fabrics and the aggressive reach of the United States in the global textile trade. We read, again and again, of ecological disasters unleashed by the fashion industry and of the repeated displacement of diverse, handmade, indigenous clothing by cheap, industrial, homogeneous garments. We learn that fast fashion... is responsible for a fifth of global wastewater and a 10th of carbon emissions.

The cotton story keeps on coming. The Xinjiang region of China is currently responsible for 20% of the world’s cotton. There’s a decent chance that you’re wearing some of it right now, as Bari points out.

Xinjiang... is now notorious for human rights infringements, the Chinese government overseeing the mass detention of Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims there in what it calls ‘vocational training centres’. Thanhauser reports how the inmates are made to work for a fraction of the minimum wage, their labour channelled into the supply chain of several recognisable high-street clothing companies.

There’s also an extract from the book—focussing on the invention of ‘ready-to-wear’ clothing—at Literary Hub.

2: Remembering Sofie Scholl and The White Rose

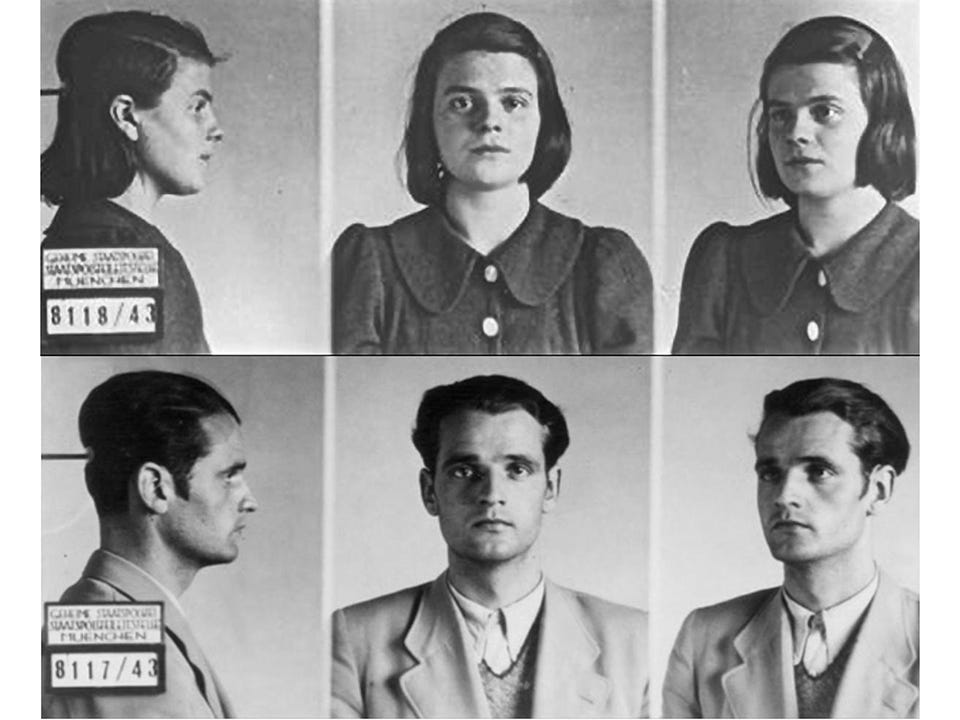

It was the anniversary last week of the execution in 1943 of Sophie Scholl, her brother Hans and their friend Christopher Probst by the Nazi regime. Calling themselves The White Rose group, they had printed and distributed a series of six anti-Nazi leaflets on the streets of Munich. She was 21 at the time. They were in my mind, perhaps, because of the courage it takes to protest in repressive regimes.

(Sophie and Hans Scholl after their arrest. Source: The White Rose Project)

Here’s an extract from one of the leaflets:

“Our current ‘state’ is the dictatorship of evil. We know that already, I hear you object, and we don’t need you to reproach us for it yet again. But, I ask you, if you know that, then why don’t you act? Why do you tolerate these rulers gradually robbing you, in public and in private, of one right after another, until one day nothing, absolutely nothing, remains but the machinery of the state, under the command of criminals and drunkards?”

—

(Image: The White Rose Project)

At the end of her brief ‘trial’ Scholl was asked if she saw her actions now as ‘a crime against the community’. She didn’t. Instead, she said to the Tribunal,

“I am, now as before, of the opinion that I did the best that I could do for my nation. I therefore do not regret my conduct and will bear the consequences that result from my conduct.”

Plough Publishing, which has published books about The White Rose, took the opportunity of the anniversary to post some letters that Sophie had written to a boyfriend in the early stages of the war. She was 19 at the time, and they are very personal—both a little giddy, but also quite reflective. Here’s one extract:

Pentecost was really glorious, though, and it’s wonderful how nothing throws nature off course. We lay in the grass with the pale green birch twigs overhead silhouetted against a sky coated with white cobwebs, and the beauty of it scarcely left room for the war and our worries. Campions suffused the grass beside the stream with red, and the dandelions were splendidly big and lush...

Spare a thought for something other than your work sometimes. Do you ever get a chance to read? My dearest wish is that you should survive the war and these times without becoming a product of them. All of us have standards inside ourselves, but we don’t go looking for them often enough. Maybe it’s because they’re the toughest standards of all.

JSTOR Daily also shared an older article on the legacy of The White Rose to mark the anniversary.

——————————-

Ukraine notes: I realise that things are moving fast and anything I share here could be overtaken by events. But from my weekend reading let me point you to the Five Books interview with Serhii Plokhy on Ukraine and Russia, which has wider perspective than the hour by hour news.

And there’s also a tremendous Twitter thread by Rasmus Corlin Christensen on what we know about where Russian offshore wealth is held. It comes with lots of supporting links, and probably won’t age that quickly.

j2t#270

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.