28 April 2022. Internet | Climate

The internet isn’t really ‘social’ at all. // New Zealand’s climate adaptation plan.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

1: The internet isn’t really ‘social’ at all

At Damage magazine, Sam Kriss has a review essay of Justin Smith’s recent book The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is. By ‘review essay, I mean that he does that thing much beloved of London Review of Books contributors where he spends the first part of the essay reflecting on his thoughts on subject under discussion, before deciding to turn to the book. Since his thoughts are interesting—he has some unpleasant personal history in this area that he seems to have reflected on—this makes for a more interesting piece.

So I’m just trying to pull out some of the more provocative ideas here, across both the essay part and the review part:

We tend to think that the internet is a communications network we use to speak to one another—but in a sense, we’re not doing anything of the sort. Instead, we are the ones being spoken through. Teens on TikTok all talk in the exact same tone, identical singsong smugness. Millennials on Twitter use the same shrinking vocabulary. My guy! Having a normal one! Even when you actually meet them in the sunlit world, they’ll say valid or based, or say y’all despite being British.

The result of this, he suggests, is that the notion of ‘free speech’ on the internet is largely imaginary. The entire “incentive structure” constructs your speech and channels it in certain directions. It is a function of connectivity. (This is a bit like the structural critique of news, that the individual views and behaviour of journalists is irrelevant, because the structure of “news” means that the news always speaks to in the same way, through a narrow range of forms.)

Anyway, these incentive structures can be ugly:

A few years ago, a friend realized that if she were murdered... then there were hundreds of people who would celebrate. She’d seen similar things happen enough times. They would spend a day competing to make exultant jokes about her death, and then they would all move on to something else. My friend was not a particularly famous or controversial person: she had some followers and some bylines, but probably her most divisive article had been about tax policy. But she was just famous enough for hundreds of people, who she didn’t know and had never met, to hate her and want to see her dead.

Similarly, he references a pile-on by a group of older novelists of a college student who preferred not to read their books. Kriss is not excluding himself from these tendencies:

Back when I spent half my days on social media, I did much the same thing. I would probably have also celebrated a murder, if the victim had once tweeted something I didn’t like. Now, looking back on those days is like trying to remember the previous night through a terrible hangover.

Some of these characteristics come from the strange state of the internet, suspended halfway between speech and writing. And, despite its claims to be “social”, it is actually a simulation of the social. Kriss references the work of the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas—“the face is what prevents us from killing.” (At this point, I’m not sure if he is paraphrasing Justin Smith—I think he may be—or still reflecting his own views).

As more and more of your social life takes place online, you’re training yourself to believe that other people are not really people, and you have no duty towards them whatsoever. These effects don’t vanish once you look away from the screen. The internet is not a separate sphere, closed off from ordinary reality; it structures everything about the way we live.

One of the consequences is a decline in empathy, and this might touch on my piece of a couple of days ago on the decline in mental health outcomes for younger people:

In 2011, a meta-analysis found that among young people the capacity for empathy (defined as Empathic Concern, “other-oriented feelings of sympathy,” and Perspective-Taking, the ability to “imagine other people’s points of view”) had massively declined since the turn of the millennium. The authors directly associate this with the spread of social media. In the decade since, it’s probably vanished even faster, even though everyone on the internet keeps talking about empathy.

Kriss is a fan of Justin Smith, who is a philosopher of science at the University of Paris, and a fan of his book.

Exactly how long have we been living with the internet? There’s a boring answer, which gives a start date some time in the second half of the twentieth century and involves “packet-switching networks.” But the more interesting answer is one that considers the meaning of the internet, rather than its technological substrate: the thought of a world lived at a distance, a dream and a nightmare that has been with us for a very long time. The internet dates back five thousand years, or five billion, or it hasn’t been invented yet. In The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is, Justin E.H. Smith pleads for the interesting answer.

Some of this is quite dense. The story here weaves its way through the Jacquard loom, through the work of Leibniz, through Ramon Llull, through Charles Babbage, indeed through a whole history of philosophy and of computing. There’s quite a lot of talk about demons as well—or daemons, maybe. It’s too tight for me to parse here, I’d say.

(A Jacquard loom. Photo by Ad Meskens/ Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

But the point is that a book called The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is is not the book that some reviewers seem to have thought it was either:

they expected a pointed screed about how the internet is ruining everything, and instead they get an erudite, quodlibetical adventure through the philosophy of computation. They wanted to be told that the internet is a sudden, cataclysmic break from the world we knew, and they get a “perennialist genealogy,” an account of how things are “more or less stable across the ages.”... Strangely, one of the things the internet likes is essays about how awful and unprecedented the internet really is. Online essays feed off rupture. Maybe the sustained intellectual activity that comes with writing a book reveals the connections instead: the way things all seem to hang together in an invisible net.

Kriss doesn’t agree with this. He thinks the internet is a break from what we had before: even “a poison”. But his exploration of why is certainly different—indeed, like Smith’s book— from most of the writing you get about the internet.

Justin Smith also has some wry and reflective thoughts on his newsletter on his experience of promoting the book, which are worth reading if you have time. (Thanks to John Naughton’s Memex 1.1 blog for this link).

2: New Zealand’s Climate Adaptation Plan

This is a short note to mark the publication by the government of Aotearoa New Zealand of the country’s first national climate adaptation plan. I’ve skimmed it rather than read it—it’s 140+ pages long— but the framing is interesting.

From the Introduction, by Vicky Robertson, who’s Chair of the country’s Climate Change Chief Executives’ Board:

It’s a very important milestone in the journey of every New Zealander to resilience and adaptation. It sits alongside the emissions reduction plan and together they lay out New Zealand’s overall response to climate change so that we can transition to a low-emissions, climate-resilient future. With this plan, for the first time as a nation we can see in one place what is being done already to adapt and proposals for what to do in the future.

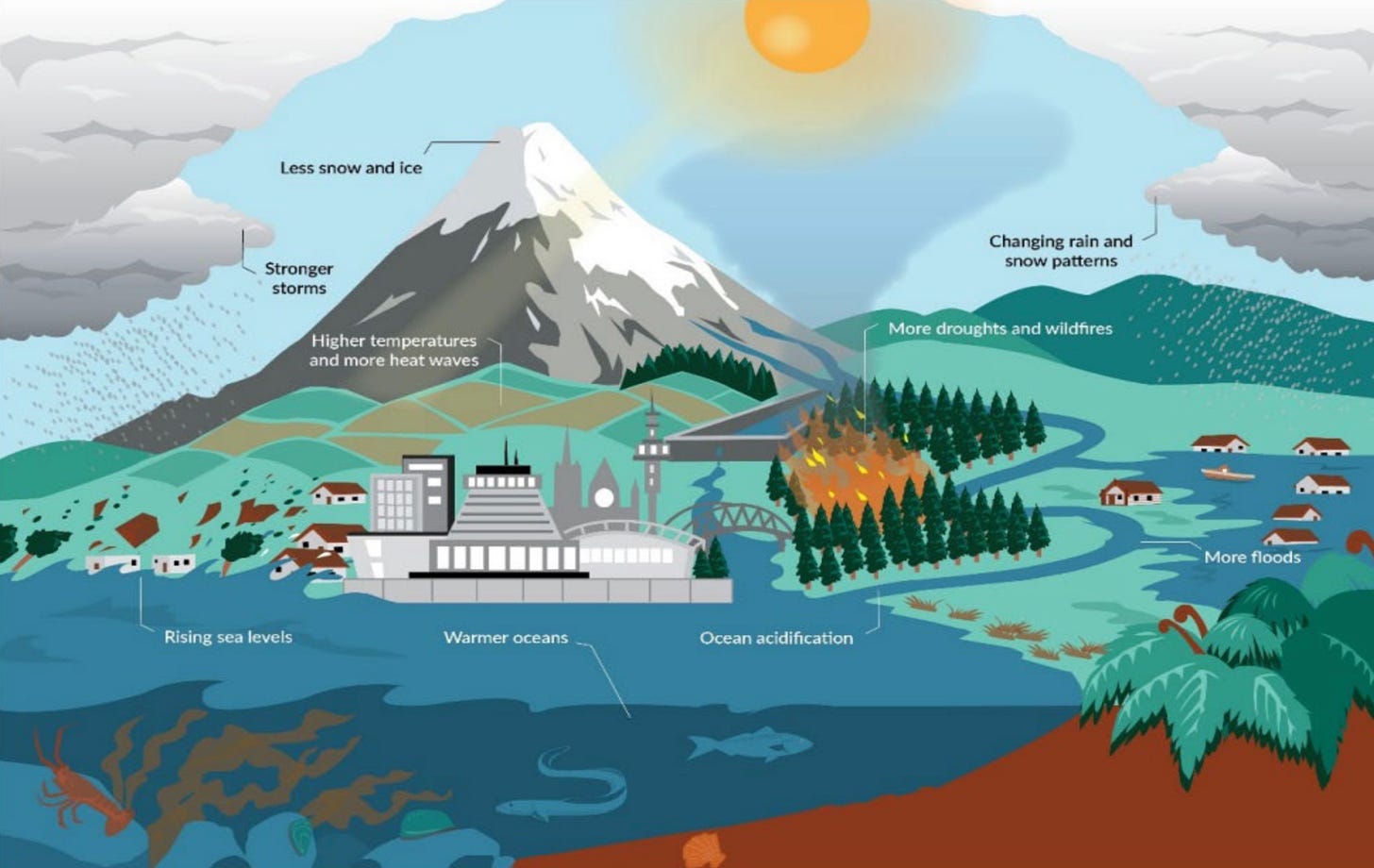

There’s a grim and familiar list of climate change impacts—extreme weather, sea level rise, drought, wildfires, brought to life in one handy single image:

(Source: New Zealand Climate Adaptation Plan)

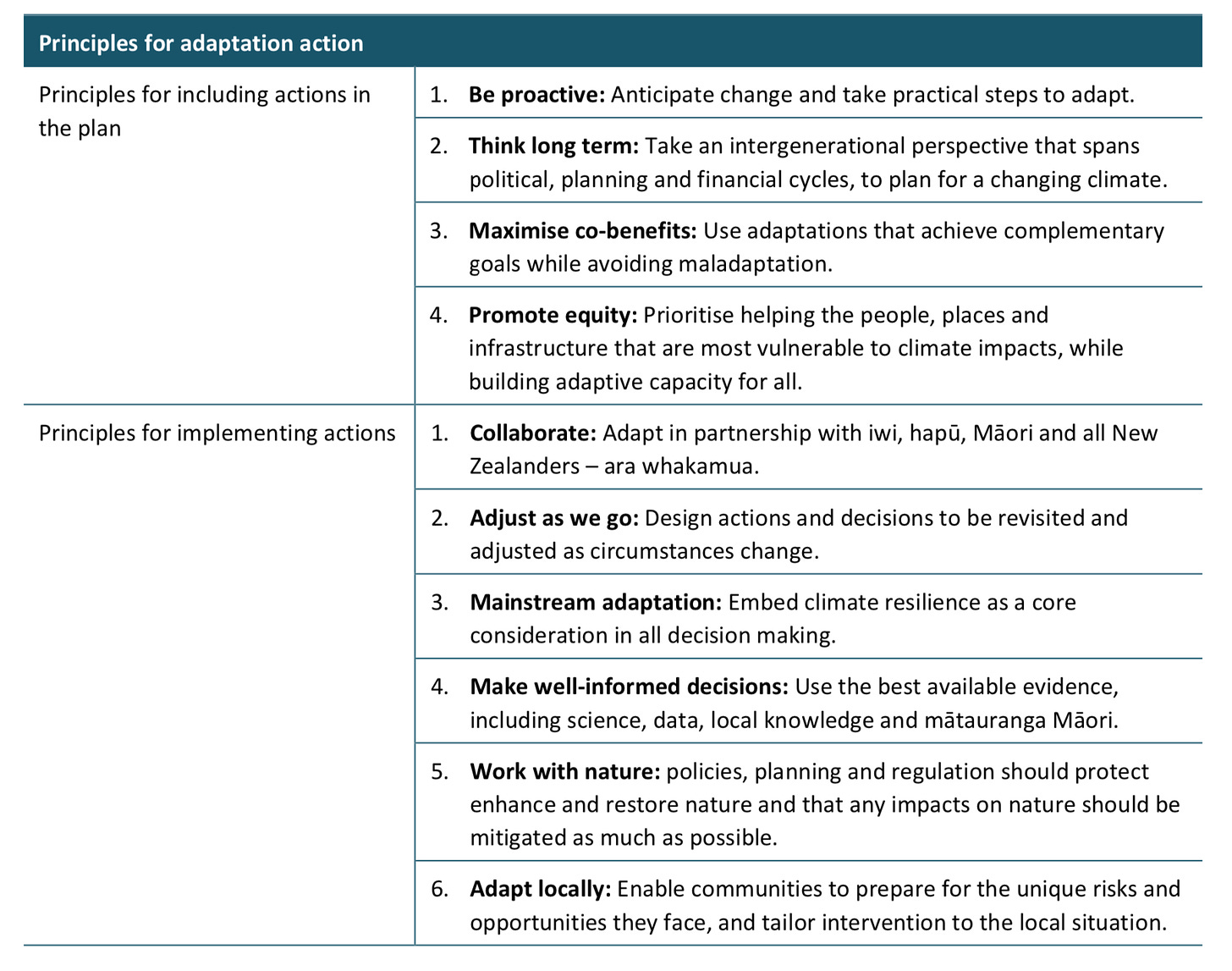

And it rehearses the country’s current risk framework and the priorities within the adaptation plan. I liked this list of 10 guiding principles for adaptation:

(Source: New Zealand Climate Adaptation Plan)

It acknowledges both the country’s indigenous peoples, and their perspectives of climate change. It shares the Rauora framework (Rauora means abundance) published separately from the national adaptation plan. This brings together Māori values and principles into an indigenous worldview of climate change.

This is from that separate document:

An indigenous world view does not work from a minimal or reductionist lens; it operates above the baseline, at the optimal, and sees stress on any composite part of the eco-system (such as over use, over allocation, degradation etc) as creating its own measurable impact on other parts of the whole. This is a blend of an inter-connectivity lens with that of inter-generational equity; and then looks additionally at the quality and state of wellbeing; and assesses that against a measure of abundance, vibrancy, regeneration and optimal health. It is not necessarily that the measuring stick for impact is inconsistent with current applications, but critically the indigenous worldview starts the measurement from a markedly different point; that of abundance, or rauora.

Much of the report is devoted to specific policy actions across different sectors that will be required to create climate adaptation for New Zealand, and proposals for future work. There are accompanying questions about the plan as well.

Update

I wrote a two part review of The Finance Curse here last week. I’ve combined this into a single article at my Next Wave blog.

j2t#306

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.