Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: The dirty business of ship-owning

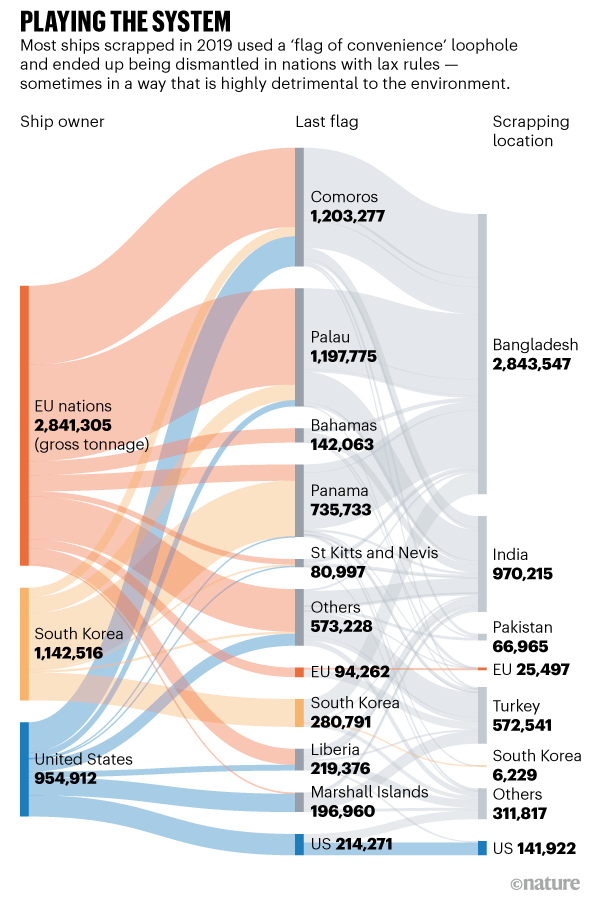

The more you know about the world shipping market, the worse it gets. A report in Nature explains the ways in which shipowners change the national flags under which their vessels sail before they break them up—to avoid the stricter environmental regulations governing ship-breaking in the country where the ship was originally registered.

The report has an exciting infographic documenting this.

This matters because shipbreaking involves huge maritime pollution, unless it is done properly:

Business owners in wealthy nations, including members of the European Union as well as the United States, South Korea and Japan, control the large majority of the world cargo and tanker fleet. But an analysis of scrapping records from commercial maritime data providers reveals that between 2014 and 2018, 80% of these ships were demolished in just 3 nations, where shipyards are governed by weak environmental, labour and safety regulations — Bangladesh, India and Pakistan.

This is part of a wider pattern. Registering ships under ‘flags of convenience’ also enables owners to avoid taxes and, potentially, safety regulations. Panama used to be the lead flag of convenience; now it is two small island countries, Comoros and Palau, which charge a fee for regulation.

The report lists some of the consequences of poor regulation of shipbreaking, for both the planet and the workers involved.

Ship-scrapping in low-income countries comes with fatal health risks and severe environmental pollution, including releases of mercury, lead, asbestos, ozone-depleting substances and pesticides into the soil and sea. One study2 estimates that by 2027, almost 5,000 workers in ship-recycling yards in India will have died from mesothelioma, a malignant tumour caused by inhaling asbestos.

The lead author of the research, Zheng Wan, a transport researcher at Shanghai Maritime University in China, notes that “Business practices are rendering many international treaties and regional regulations unenforceable because ‘flags of convenience’ nations tend to have little interest in regulation.”

And generally, when it comes to regulating sector, people complain about both the weakness of the existing international agreements and the difficulty of changing them.

But there’s a straightforward way to enforce better behaviour by shipowners—which is simply to deny their ships landing rights if they are flying under flags of convenience, or if they break up their vessels in ways that damage people and planet.

Because cargo ships are mostly in the business of shipping goods to larger, richer countries which generally have higher environmental standards. So a ship that can’t access the ports in these countries is immediately worthless. Rotterdam has, I believe, already done something similar about ships that are polluting the water.

#2: Playing for a thousand years

I’m giving half of the annual John Logie Baird lecture to the IET later today, peering into the gloom to make sense of future media. (It’s the IET’s 150th anniversary this year). More on that next week, perhaps, but my research took me back to look at Jem Finer’s Longplayer project.

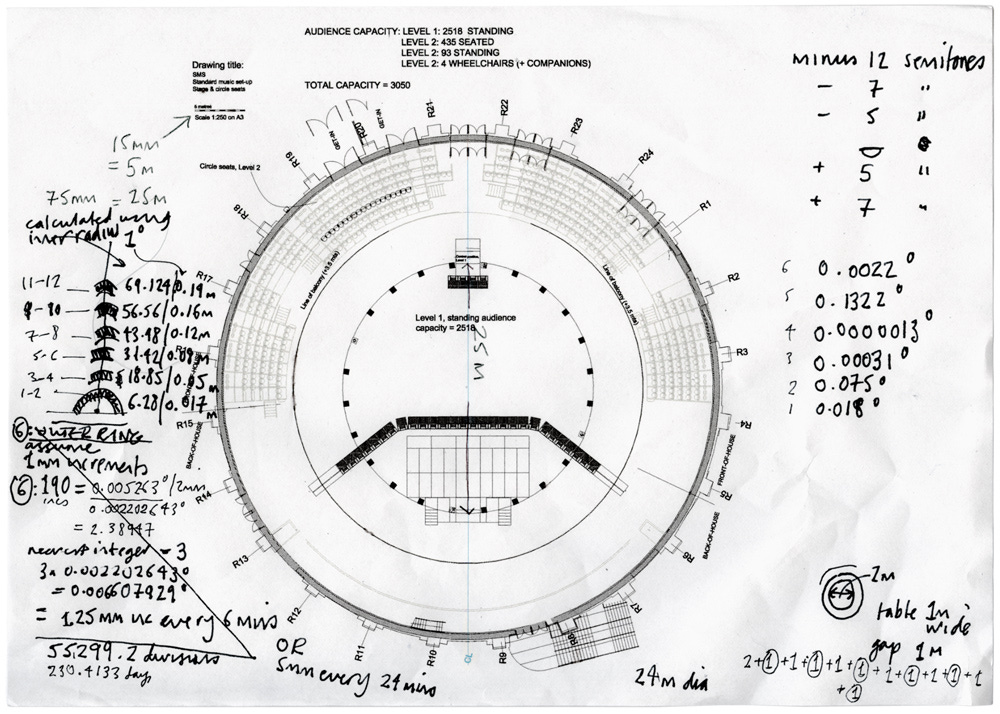

Longplayer is a piece of music that is designed to play for 1,000 years without repeating itself. It’s currently 21 years in. Finer says that the music will also evolve slowly over the centuries, but I guess we’ll have to take his word for that.

Image: Jem Finer, Early calculations for Longplayer Live, via longplayer.org

What caught my eye was a section on the website where he discusses the challenges of maintaining the piece over that time scale.

The challenges fall into three areas: distributing it, producing it, and looking after it.

On distributing it, he doesn’t think the current internet model is sustainable:

At present Longplayer is being streamed live on the internet – a medium which, while at present truly global and virtually instantaneous, depends on both a vast, complex, and somewhat unstable technological network for it broadcast and a high technological “overhead” for its reception. Radio, on the other hand, depends on a relatively simple and stable technology for both broadcasting and receiving, to the extent that it can even be heard on a homemade wind-up device.

In terms of producing it, he discusses several options: either producing it through a mechanical model where parts can be replaced (it’s currently coming from an assortment of computer systems) or a single function closed computing device, similar to those used in deep space probes.

But you could also use people:

If Longplayer is to survive at all, then people will have to want it to. So, ultimately, the best strategy might be for it to be played by humans – as long as they are around. In theory, once a stable platform for human performance is established – a durable or easily replacable set of instrumental tools, an accurate methodology and a means of conveying this methodology from one generation to the next – future performers would be able to pick up the performance at any given point in time based on a set of simple calculations.

People are also needed to look after it—for 40 or so generations.

What I liked about this discussion, of a very specific application, is that working it through immediately challenges some of the hot takes we get—usually framed by Silicon Valley’s particular interests—on how the longer term future might be organised.

Anyway, you can listen to Longplayer here:

https://longplayer.org/listen-files/longplayer.pls

j2t#106

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.