27 October 2021. Trees | Literature

A lot of tree-planting schemes don’t work. This year’s Nobel Prize winner: “everything is shifting”.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. (For the next few weeks this might be four days a week while I do a course: we’ll see how it goes). Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: A lot of tree planting schemes fail. It’s more complicated than that.

As concern over climate change has grown, the push to plant trees has accelerated. Trees absorb carbon and can be used to offset emissions, so what’s not to like? And according to Vox there are now no fewer than three organisations, including the World Economic Forum, that are committed to planting a trillion trees.

Unfortunately, a lot of these large scale tree planting initiatives fail:

On November 11, 2019, volunteers planted 11 million trees in Turkey as part of a government-backed initiative called Breath for the Future. In one northern city, the tree-planting campaign set the Guinness World Record for the most saplings planted in one hour in a single location... Less than three months later, up to 90 percent of the saplings were dead, the Guardian reported. The trees were planted at the wrong time and there wasn’t enough rainfall to support the saplings, the head of the country’s agriculture and forestry trade union told the paper.

The idea of planting millions upon millions of trees seems to have accelerated in 2011 with the Bonn Initiative and gained momentum in 2019 by a contested paper in Science—the same paper that inspired the World Economic Forum campaign.

While many scientists criticized the paper, the idea behind it — that we can plant our way out of climate change, while simultaneously solving other problems like biodiversity loss — has stuck around. It’s a charming notion that’s much easier for companies or countries to act on, compared with doing the hard work of slashing greenhouse emissions.

The Vox article notes that tree-planting campaigns are well-intentioned, but they have high failure rates. They often don’t deliver the carbon capture benefits they promise, or creating habitats for new species. Some schemes actually harmed existing ecosystems. The article has examples of such failures, in India, Mexico, Pakistan, and Brazil.

But it’s one thing to criticise failure. Given that trees do capture carbon, what should we be doing instead?

The first thing is to concentrate on tree-growing rather than tree-planting.

Even fast-growing trees take at least three years to mature, he added, while others can require eight years or more. “If our thinking of growing trees is downgraded to planting trees, we miss that big part of the investment that is required,” (climate scientist Lalisa) Duguma said.

The second is to look at the underlying social and economic conditions that cause deforestation—which might be down to people needing firewood or other materials.

People may cut down trees to collect firewood or carve out land for their animals. In those cases, putting seedlings in the ground won’t do much to end deforestation. “Planting trees might not be the intervention,” (environmental researcher Forrest) Fleischman said. “The intervention might be giving people a substitute for firewood.”

Long-term, the only real solution is to work with the grain of rural and indigenous peoples. The article points to a notable success story in Brazil, where a non-profit has planted 2.7 million native trees over 35 years—trees that have provided fruit, building materials and an income stream to the local communities.

But the hardest truth here is that planting trees isn’t a magic bullet. As one of the researchers quoted here observes:

“we’re not going to plant our way out of climate change.”

A forest corridor in Pontal do Paranapanema, Brazil. Courtesy of Laurie Hedges/Instituto de Pesquisas Ecológicas. Via Vox.

#2: This year’s Literature Nobel Prize winner: “everything is shifting”

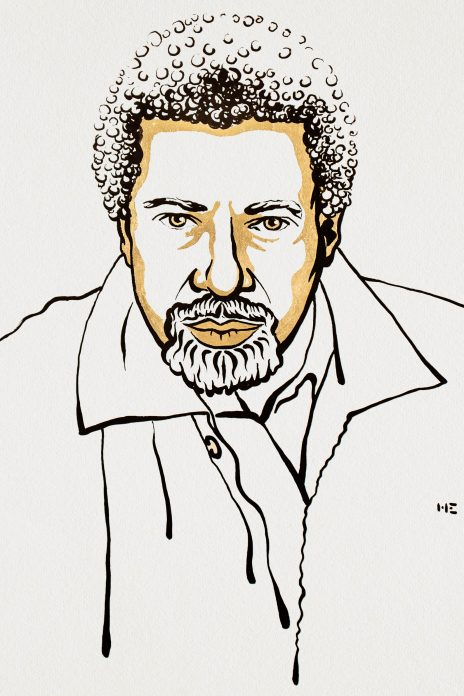

This year’s Nobel Prize winner, Abdulrazak Gurnah, was born in Zanzibar, but has spent most of his adult life working in Britain. An important theme of his work is dislocation and exile. He is the fifth African writer to win the Prize.

I’m interested in this because there are always reasons beyond the quality of the work that sit behind the Nobel Committee’s award. Their citation commended his “uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents.”

(Illustration by Niklas Elmehed © Nobel Prize Outreach)

One of the best articles I found on his work was in the Indian paper Indian Express. The author, Paromita Chakrabarti, amplifies the Nobel Committee’s observations:

In most of his works, Gurnah eschews nostalgia and upends genre tropes to show the tension and insecurity latent in the constantly shifting sands of displacement. In By the Sea, another novel nominated for the Booker Prize, he explores the refugee’s struggle to both remember and to forget.

“It is difficult to know with precision how things became as they have, to be able to say with some assurance that first it was this and it then led to that and the other, and now here we are. The moments slip through my fingers. Even as I recount them to myself, I can hear echoes of what I am suppressing, of something I’ve forgotten to remember, which then makes the telling so difficult when I don’t wish it to be,” says one of the narrators, Saleh, a Muslim man from Tanzania who seeks asylum in the UK.

She also references Gurnah’s 2004 essay, ‘Writing and Place’:

at the time I left home, my ambitions were simple. It was a time of hardship and anxiety, of state terror and calculated humiliations, and at 18, all I wanted was to leave and find safety and fulfilment somewhere else. I could not have been more remote from the idea of writing.... I began to write casually, in some anguish, without any sense of plan but pressed by the desire to say more. In time, I began to wonder what the thing was that I was doing, so I had to pause and deliberate. Then I realised I was writing from memory, and how vivid and overwhelming that memory was, how far from the strangely weightless existence of my first years in England.

There’s a strong flavour of this in the Nobel Committee’s citation, which also contains a review of Gurnah’s different books:

Gurnah’s itinerant characters find themselves in a hiatus between cultures and continents, between a life that was and a life emerging; it is an insecure state that can never be resolved.... His novels recoil from stereotypical descriptions and open our gaze to a culturally diversified East Africa unfamiliar to many in other parts of the world. In Gurnah’s literary universe, everything is shifting – memories, names, identities.

I’d also recommend Fawzia Mustafa’s piece in The Conversation on Gurnah’s work.

j2t#195

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.