26 September 2022. Food | Future generations

The scale of the food crisis // Influencing the million year future

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: The scale of the food crisis

The daily post/email from the food academic and blogger Marion Nestle alerted me a few weeks ago to the latest edition of the Food and Agriculture Organisation’s report, The state of the world’s land and water resources for food and agriculture, acronymmed throughout as SOLAW.

I’ve now had a chance to dip into it, although quickly rather than carefully, since it runs to more than 350 pages. So let me quote her summary of the problems listed in the report. It’s not a happy list:

- Human-induced soil degradation affects 34 percent – 1 660 million hectares – of agricultural land.

- More than 95 percent of our food is produced on land, but there is little room for expanding the area of productive land.

- Urban areas occupy less than 0.5 percent of the Earth’s land surface, but the rapid growth of cities has significantly impacted land and water resources, polluting and encroaching on prime agricultural land that’s crucial for productivity and food security.

- Land use per capita declined by 20 percent between 2000 and 2017.

- Water scarcity jeopardizes global food security and sustainable development, threatening 3.2 billion people living in agricultural areas.

The report is dated 2021, although published this month. Its sub-title is: “Systems at breaking point”. The first SOLAW report was for 2011, and covered a long list of risks to food and water systems. Things have got worse since then. It’s also worth noting that the report is stacked full of data and case studies on world food and water systems.

The report uses an approach described as “driver–pressure–state–impact–response”. I wasn’t familiar with this, although it makes sense, and also provides a structure to both understand cause/effect relationships and to identify policies that might have a chance of making our use of land and water resources more sustainable.

Here’s a summary of the main points the report makes using this approach (pp xvii ff).

The drivers of demand for land and water resources are complex. By 2050, FAO estimates agriculture will need to produce almost 50 percent more food, fibre and biofuel than in 2012 to satisfy global demand and keep on track to achieve “zero hunger” by 2030. Progress made in reducing the number of undernourished people in the early part of the twenty-first century has been reversed... Options to expand cultivated land areas are limited...

Most pressures on the world’s land, soil and water resources derive from agriculture itself.

These include: chemical inputs, monocropping and higher grazing intensities, and mechanisation, all concentrated on a declining amount of agricultural land. The result:

a set of externalities that spill over into other sectors, degrading land and polluting surface water and groundwater resources.

The impacts:

The impacts from accumulating pressures on land and water are felt widely in rural communities, particularly where the resource base is limited and dependency is high, and to a certain extent in poor urban populations where alternative sources of food are limited.

The central challenge here is to increase land and water productivity while also reducing land degradation and the pollution and loss of environmental services that goes with it. Because food productivity underpins a whole group of desired outcomes, such as “food security, sustainable production and SDG targets.”

There’s 60 or 70 pages here of responses, many local or regional case studies from different parts of the world. Reading these suggest that solutions do exist, but they haven’t yet scaled.

Here’s the list of the four main responses, written in that bland UN report language that seems designed not to frighten anyone (p255):

Land and water governance needs to be more inclusive and adaptive. Inclusive governance is essential for allocating, planning and managing natural resources to continue to meet increasing demands....

Integrated solutions need planning with stakeholders and need to be mainstreamed to take them to scale....

Technical and managerial innovation needs to be targeted to address priorities, reduce risks and enhance resilience of people and ecosystems. ...

Agricultural support and investment should be redirected towards social and environmental gains derived from the range of land and water management solutions available, leaving no one behind.

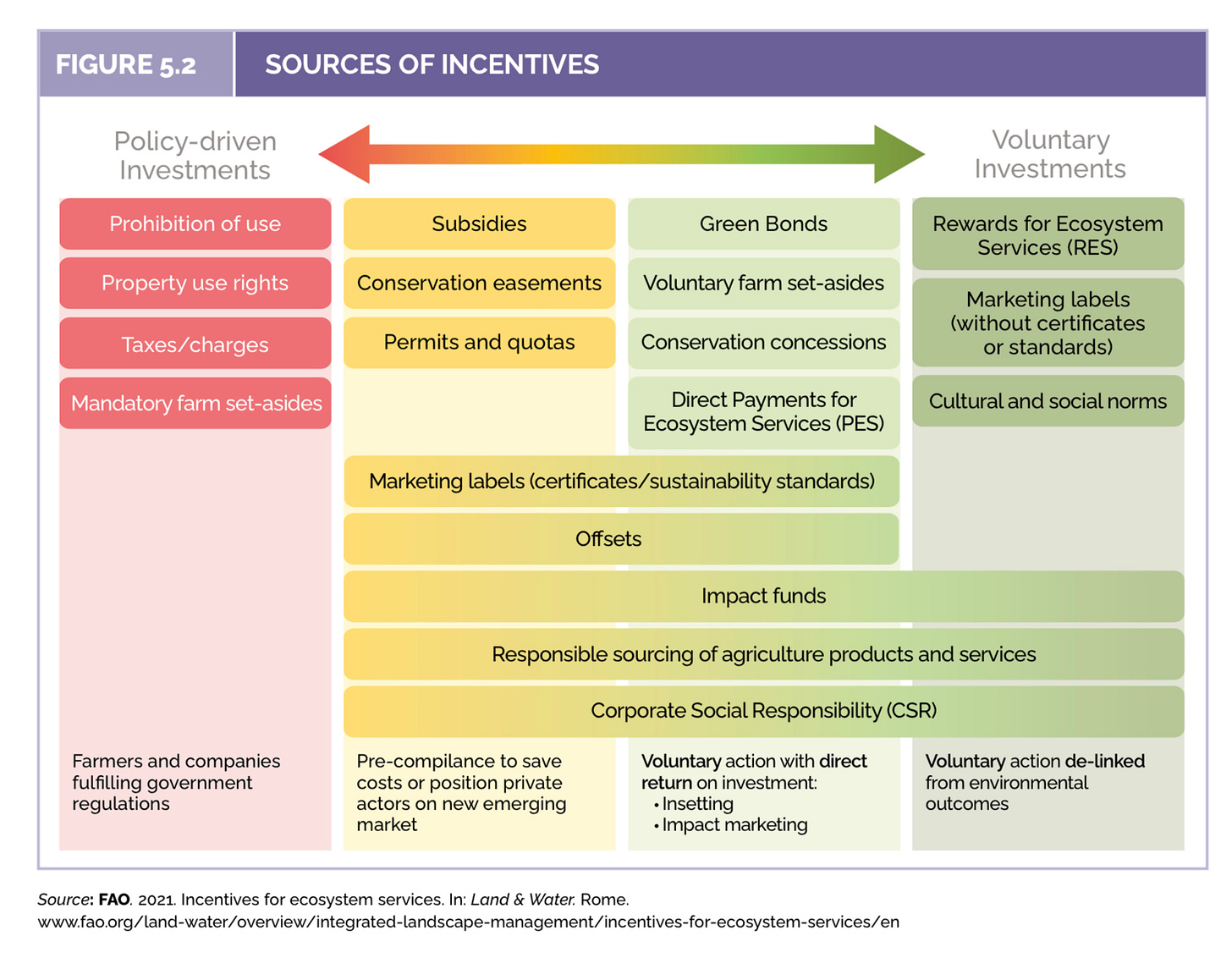

There’s a useful diagram of different types of incentives that can help with all of this.

(FAO, SOLAW report 2021)

You don’t really need to read much between these lines to see that these are issues of politics rather than a set of technical questions. I couldn’t find a section anywhere that said that the big vested interests in the food system seemed happy with short-termist business. (UN reports tend to skirt around big vested interests, hoping to bring them onside).

Equally, related to this, many of those at the other end of the food system—poorer, more disadvantaged, rural—don’t get to share in the benefits of technical advances. There’s therefore no incentive for them to adopt them, assuming that they could afford such investment in the first place.

There is a raft of measures already in place that are designed to help make these changes, and the report spends some time on this. Governance and legal changes, such as reinforcing tenure rights, seems to help (but see politics, above). Rebalancing payments towards ecosystems services is good—something the British government has just abandoned in its latest wrecking-ball budget, by the way.

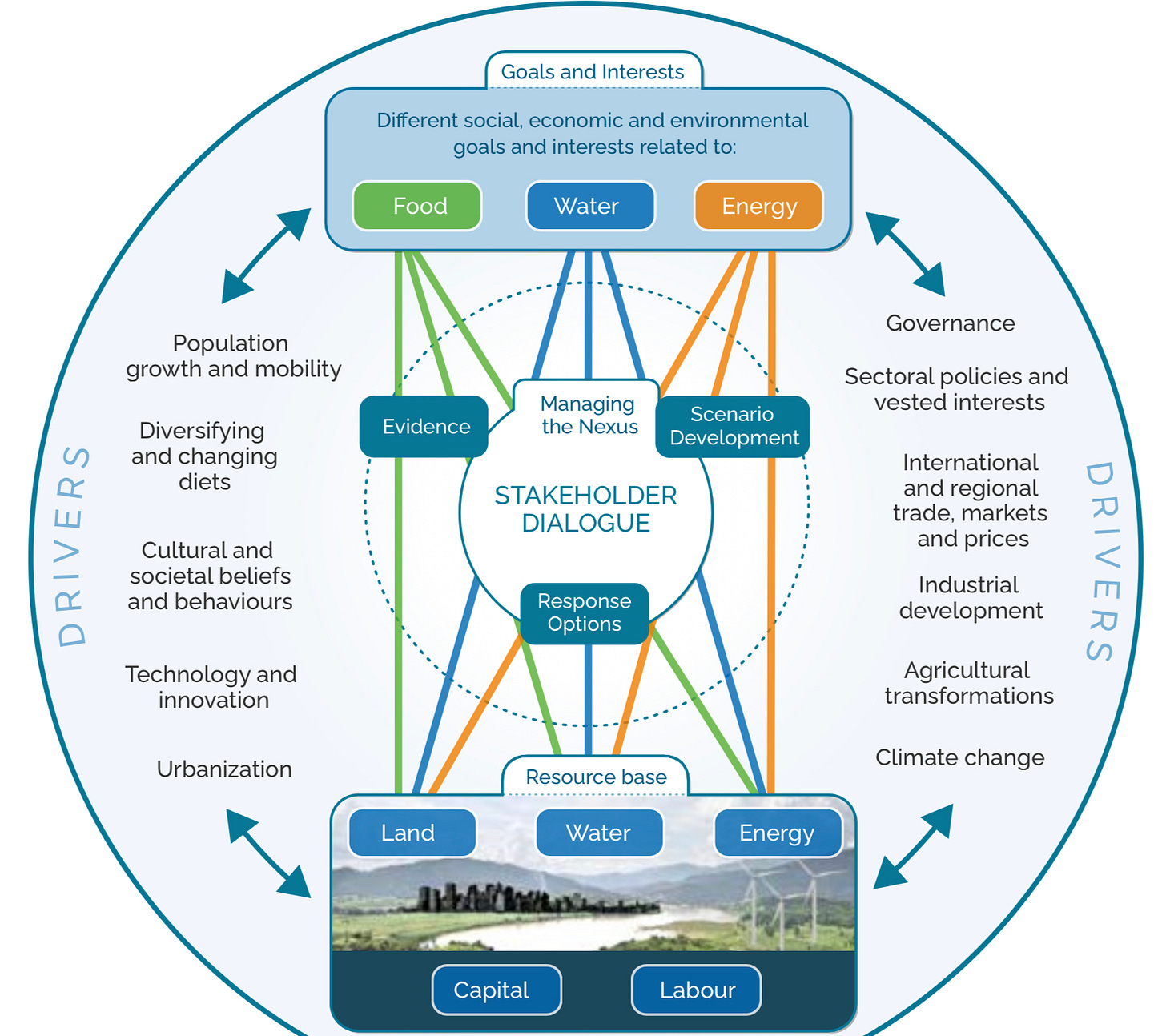

But all of this needs effective engagement with a lot of stakeholders, who either need to be convinced of its urgency or (in the case of poorer farmers) helped with the resources they need to act. I liked the ‘Nexus’ diagram that connected these together (p276) even if I wondered how this might work in practice. There’s a link in the SOLAW report to an earlier account of this.

(‘Nexus’ diagram: FAO, SOLAW report 2021)

In short, this is no longer a technical question. It’s about managing politics and governance, and investing in capacity and capabilities. It’s another area where we know there’s a crisis, we more or less know what we need to do about it, but getting vested interests to agree to change is essential to success. No wonder Marion Nestle called the report “a dose of reality”.

2: Influencing the million year future

William MacAskill’s new book, What We Owe The Future is getting a fair amount of attention and reviews. He is a philosopher at Oxford University, and the book takes a million-year view of the future—arguing that “positively influencing the longterm future is a key moral priority of our time.”

I’m comfortable with this idea, not least because the wellbeing of future generations has been a core piece of the work done by the School of International Futures over the last few years.

MacAskill comes to this from the perspective of “Effective Altruism”, and I have more doubts about this part of the story, both philosophically and practically. Philosophically: One of the practices of effective altruism, for example, is to take well paid jobs and then give away income that you deem surplus to good causes.

In theory that sounds straightforward, but it’s impossible to know if your well-paid job in (say) an investment bank is doing more systemic harm than the good you’re doing in giving away a part of your income. I’m willing to concede that this probably doesn’t apply to Oxford philosophy dons.

Practically, in terms of looking at harm, the EA movement is obsessed with general AI, to the extent that it neglects other more likely and more imminent sources of harm, such as climate change or biodiversity collapse. (Thanks to my son for showing me the research on this in practice). This also speaks to a wider point about harm in the EA view: it’s about harm to future humans, not non-human species.

But I probably need to park all of that for the moment, and pick up Jeremy Williams’ review of What Do We Owe The Future:

The book begins with an explanation of how short the human experience is on a geological scale. Looking to the future, it’s quite likely that we are in the early stages of the human story, which means that the future is “where almost everyone lives and where almost all potential for joy and misery lies”. These future people shouldn’t be discounted, and our actions today can shape their lives.

MacAskill also argues that we are currently at a moment where our futures are relatively open, which means that the choices we make now matter. This isn’t always the case:

The opportunity to shape the future might not remain open for long though. Looking at Chinese philosophy, MacAskill shows how history moves from times where there are competing schools of thought, to eventual dominance that can endure for centuries. We live at a time of ‘plasticity’, where there are multiple visions for a good society, which is a good thing – it’s an opportunity to evolve and develop. Sooner or later, a set of values might get ‘locked in’ and hard to change.

And—assuming that we do survive as a species—there are going to be more humans in the future than there have been in the past, and potentially a lot more.

Ultimately, considering the possibility of a long and flourishing human future leads to the conclusion that safeguarding the future matters. Extinguishing civilization – whether that’s through climate change, nuclear war or manufactured pandemics – would not just harm life today, but snuff out the possibility of flourishing life in the future. And that future life and happiness would be vastly greater than life today, making existential risk a vital moral priority.

This takes Williams back to the limits of Effective Altruism: “in focusing on future life, they risk turning their backs on those suffering now. The result is philanthropy without solidarity, without empathy, reduced to abstract mathematics and balance sheets.” In this context, he references the Gil Scott-Heron song ‘Whitey on the Moon’, which you do think would go straight past the EA crowd.

At the FT, but probably behind their paywall, the economist Tim Harford has also reviewed the book. Given his very different perspective—Williams is an environmentalist, Harford an economist—it is interesting that they end up focussing on a similar concern. Harford approaches this from the perspective of the discount rate:

MacAskill does not seriously engage with the question of the human propensity to discount the future... “Harm is harm,” says MacAskill. That is true “whether it’s a week, a decade, or a century from now”. This suggests a discount rate of zero, although the term does not appear in the book’s index. It is a radical suggestion, but he offers no argument in favour of this view.

This opens up a set of moral questions that Harford feels “are waved away in a few sentences”:

If he is right, how could I justify giving £10 to a food bank today when I could set up a charitable trust, let the money accumulate centuries of compound interest before lavishing the proceeds on future generations? Are we morally obliged to live at subsistence levels to maximise the resources available for investment and research so our great-great-great-great-grandchildren will thrive?

All the same, Harford enjoyed the book, despite his disagreements. For his part, Williams clearly spent most of the time he was reading the book arguing with it, which isn’t a bad thing, of course. But he definitely recommends it:

there’s no question that it’s a thought-provoking, original and profound piece of work. It has a lot to offer on long-term thinking, on how we see ourselves and our present moment, and the idea that there is just so much of the future to fight for.

Thanks to Jamie Saunders for the reminder about the book.

——————————-

j2t#372

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.