26 October 2022. Rest | Health

Rest as a response to ‘grind culture’ // Our public health blindspot

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Rest as a response to ‘grind culture’

Stowe Boyd’s excellent newsletter on trends in work alerted me to the fact that Tricia Hersey’s Rest is Resistance: A Manifesto is in the New York Times bestseller’s list. Hersey is known for her work on The Nap Ministry—which advocates napping as a form of self-care—and Boyd quotes an extract from the book in his piece:

Grind culture has normalized pushing our bodies to the brink of destruction. We proudly proclaim showing up to work or an event despite an injury, sickness, or mental break. We are praised and rewarded for ignoring our body’s need for rest, care, and repair. The cycle of grinding like a machine continues and becomes internalized.

From a futures point of view, it’s immediately of interest that a fairly militant book on rest is a New York Times bestseller. And manifestoes are catnip to futurists, so I went looking for a review. The most extensive one was by Megan Volpert at Pop Matters.

Volpert had drawn on The Nap Ministry when she was escaping from the fatigue of work as a teacher, and was a willing reader of Rest is Resistance. The book is divided into four parts: rest, dream, resist, and imagine.

In the section on rest, the author situates herself among the Black liberationists and explains how she has been called to spread the messages of rest since they saved her exhausted life. Moreover, because capitalists, racists, patriarchs, and their ilk rely upon the body to instill grind culture, resistance to these must also be embodied.

Hersey is an Afrofuturist, and “dream” is where the work of imagining different world is done:

Using our imaginations to envision this future free from grind culture is how we can begin to resist. In that sense, the future is now. We can rest right now, and the remaining two sections of Rest Is Resistance focus on the beautiful struggle of trying to do that... No part of this world encourages or assists us in resting, so we must snatch rest for ourselves.

All the same, Volpert finds the book a bit of a let-down (her word). This is partly down to a theoretical disagreement: she feels that Hersey fails to engage sufficiently with questions about technology:

The can of worms for all revolutionary roads is that they must pass through the wide open gateway of Donna Haraway’s A Cyborg Manifesto (1985), which allows equal chances that technology can save us or destroy us. Hersey’s book comes down on the side of technology destroying us, never acknowledging the other possibility—which she should. Technology could ultimately give us a huge amount of our time back for resting.

It’s also down to the style, which Volpert finds repetitive, or circular, although it’s also possible that is a deliberate stylistic choice by Tricia Hersey.

(‘Noon, rest from work’, by Vincent van Gogh. Musee d’Orsay, public domain.)

I’ll leave that discussion to the reader, because the more interesting part of the review is Volpert’s discussion of the manifesto as a form. She’s taught it as a subject, and in this two themes emerge. The first is that there are no alternatives to the present system; the second is that they are about anger.

On the first:

Hersey’s alternative to grind culture is rest, but let’s imagine that her project truly brings on a community revolution where—I’m reductively short-handing here—our entire planet naps to defeat capitalism. Then what? What leaps in to fill the vacuum left by the erasure of our present systems?

On anger, well, as Volpert says, rest is a hard subject to be angry about, and Hersey doesn’t try. But in many manifestoes, anger acts as a counterpoint to seriousness. If you’re not going to be angry, you probably need some humour to be that counterpoint instead.

If a manifesto isn’t angry, it must rely on a bit of humor as another option for the tip of the spear. There are some truly hilarious and campy manifestos, particularly those offering a queer feminist take. The Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell (WITCH), Jo Freeman’s Bitch Manifesto , and the Queer Nation Manifesto . Even the ones that appear to condone murder, such as The Chicks’ song “ Goodbye, Earl ” and the infamous S.C.U.M. Manifesto , are full of wisecracks.

Hersey’s style instead is more drawn from preaching, which is “perhaps a more performance-based cousin of the manifesto”, and Volpert worries that this might restrict the appeal of the book—although perhaps the New York Times bestseller list says otherwise.

For her part, Volpert expects to be dipping into the The Nap Ministry’s Instagram account more than the book, but still thinks that the book is worth a read:

Hersey understands that true resistance is communal, so she doesn’t expect her rest project alone to solve our modern-day systemic challenges. Rest Is Resistance offers one layer in a manifold project of revolution and is worthy of a read for anyone—anarchist, socialist, feminist, liberationist, philosopher, lover of manifestos—looking to add rest back into their life and add to the methodologies they are already using to destroy grind culture.

2: Our public health blindspot

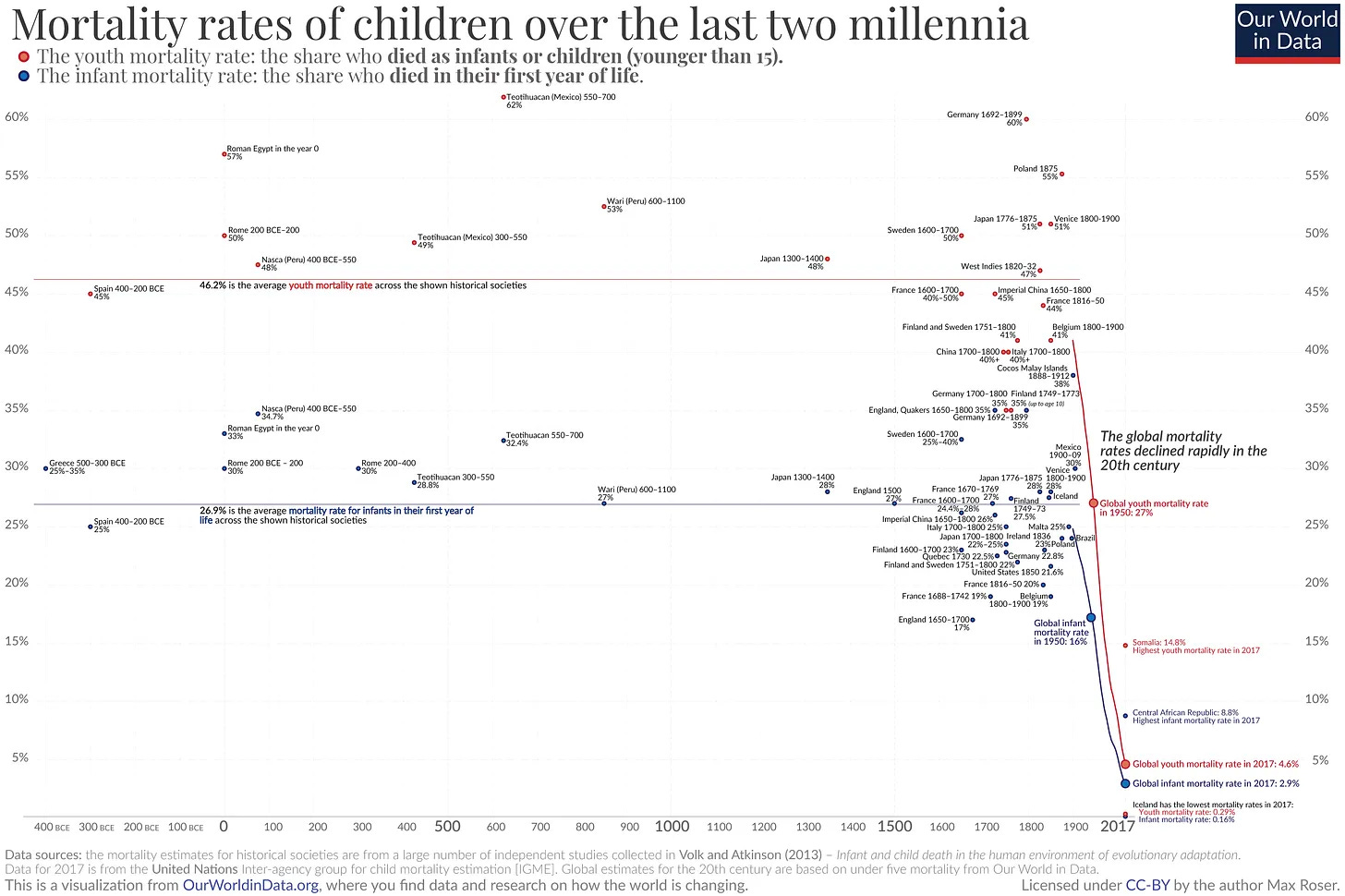

Steven Johnson, who mostly writes about innovation, asks an interesting question in a recent edition of his newsletter: in the way we teach history, why don’t we notice the vast decline in child mortality that has happened over the past century or so. Because the data are staggering:

(2000 years of child mortality. The action is at the right hand edge. Licensed under CC-BY by the author Max Roser.)

Childhood went from being the most dangerous time of your life—unless you were lucky enough to live to be very old—to being the safest. All the other achievements of modernity really pale in comparison to this one. Sure, it’s nice to have refrigeration and electric light and supercomputers in our pockets, but I think most of us would trade all of that to avoid a 40% chance of dying before adulthood.

Johnson starts his piece by writing about ‘The Sick Child’, a painting by Edvard Munch of his sister Sophie—a painting he revisited three times in his life. Sophie died of tuberculosis at the age of fifteen. As Johnson notes:

Until very recently, it was simply a given for parents that more than a third of their children died before adulthood, in both the richest countries in the world and the poorest. Today global youth mortality stands at 4%, and in many wealthy countries with robust health safety nets that number is closer to 1%.

Part of this piece is about how this history is completely overlooked in our history books. He takes the example of an “otherwise excellent” American textbook covering the last 150 years, which he does a keyword search of:

Just to give you some context, the textbook mentions “labor” 226 times, “weapons” 28 times, “automobiles” 20 times, “civil rights” 134 times, and “taxes” 58. Those seem at first glance like appropriate ratios for a textbook of several hundred pages. But when you turn to the achievements of public health and medicine, you get very different results. “Public health” itself is mentioned twice, “sanitation” (in the context of public sanitation, like sewer systems) is mentioned once; the words “antibiotics,” “penicillin,” “vaccines” never appear at all.

Johnson wonders why this is, and doesn’t really answer his own question. I’d suggest a few reasons: we’re better at seeing stuff (like new technologies) than we are at seeing changing systems, which are somehow more invisible. We’re also better at telling stories which have narratives, and narratives work better with enemies; disease is a bit abstract when it comes to enemies.

Still on narratives, it’s easier to track the history of prominent individuals than it is the behaviour of many less prominent people: hygiene in hospitals was usually improved by nurses noticing the effects of soap while doctors dismissed the idea.

Similarly, we’re not that good at noticing long-term slow-moving change—the long-term effects of lower fertility levels across the world only really gets attention when it fuels protests, as in Iran at the present.

One of my own frustrations as a futurists is the endless discourse around health futures that looks at the individual (“the quantified self”, etc etc), when the big gains in health are to be made at the level of public health, and often from outside the healthcare sector. Changing the way the food sector works, for example.

(‘The Sick Child’, by Edvard Munch, 1927. CC BY-SA 4.0)

So this blindness does have consequences. In the area of public health, for example, as Johnson says:

If you happen to be a child, the historical development that most dramatically changed the quality of your life over the past 150 years is the simple but astonishing fact that your odds of dying before adulthood were reduced by a factor of ten. And on the pattern recognition front, we might have less vaccine hesitancy and anti-science belligerence today if we bothered to mention the miraculous development of antibiotics or modern vaccines in our history textbooks.

Maybe there’s an analogy here with addressing climate change—and sadly, it’s not an encouraging one. It is, similarly, a story about systems change; it is slow moving; it’s not one that makes for easy narratives (maybe outside of Greta Thunberg); the enemy is, literally, invisible; and dealing with it is about absences—the thing not bought, the journey not made—rather than stuff.

j2t#386

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.