26 June 2023. Elites | Tourism

Elites, political disintegration, and ‘cliodynamics’// Dark tourism, rich thrills [#471]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Elites, political disintegration, and ‘cliodynamics’

In his recent book End Times, Peter Turchin tries to lay out his story about social, political, and economic change for a popular audience. The book is given added immediacy by its publisher’s subtitle: “Elites, Counter-Elites, and the Path of Political Disintegration”. I know Turchin’s work quite well, and I know his underlying model well enough, and I think that End Times fails in this objective. I’ll come back to why this is later on, but first a bit of background on the underlying model and its intellectual history.

This turned into a longer review than I was expecting, so I am also going to split it across two editions of Just Two Things. The second part will be on Wednesday.

Turchin was an evolutionary biologist by background, and his early hypothesis, which brought him into the area of history and social sciences, was that you might see similar patterns in population pressures in human societies that you see when looking at animal groups. It’s not an unreasonable hypothesis.

(Photo: Andrew Curry. CC NC-BY-SA 4.0)

In his first book which detailed the model, Secular Cycles (2009), written with Sergey A. Nefodov, they described these as ‘structural-demographic cycles’, which drew on the work of the historical sociologist Jack Goldstone. They explored this idea across eight time periods, all pre-industrial, across four geographies. They included, for example, both Plantagenet England and Tudor-Stuart England, and Muscovite and Romanov Russia.

The model in Secular Cycles is explained fairly clearly (p. 33), and I’m going to summarise it here.

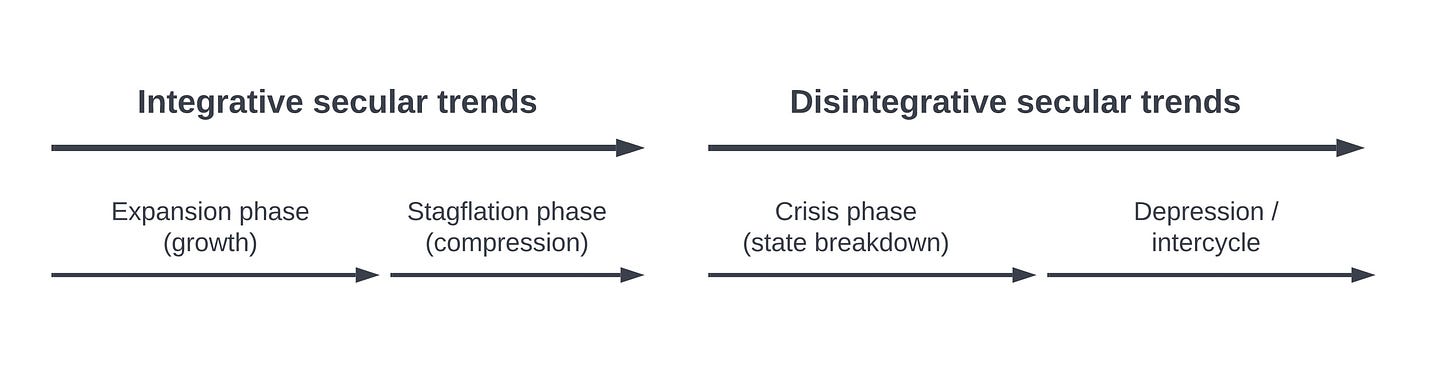

The ‘cycle’ includes a long ‘integrative’ phase and a long ‘disintegrative’ phase. The integrative phase falls into two parts: an expansion phase, which involves growth, and a ‘stagflation’ or ‘compression’ phase. The disintegrative phase is messier, but has a ‘crisis’ phase involving state breakdown and a depression phase, which can also just be a stage of ‘intercycle’ stagnation before the next growth phase starts.

(Source: Peter Turchin and Sergey A. Nefodov. ‘Secular Cycles’, p.33)

Long? We’re talking generational timescales—this whole cycle can take between 100 to 300 years, depending on how easy it is to replace your elites.

The narrative of the original model goes like this:

Initially, workers (or peasants) are making a reasonable living. But that means that population increases—more children are born, people are better fed and less likely to die. So the population starts to approach carrying capacity.

As population reaches carrying capacity, there are more people (so wages are squeezed) but increased demand for food and land)—so wages are doubly squeezed.

But at the same time, the asset values of landowners, and their returns from food production, both increase.

This shifts demand patterns towards things that the wealthy want to pay for, so you also see new industries start to emerge.

You also see increasing numbers of the elite, and increasing competition for elite position, which creates instability. In this ‘stagflation’ phase inequality increases at all levels of society; extraction intensifies.

One of the effects of this is that the state becomes more unstable. It finds it harder to raise money, for example.

Typically there are food riots and patchy rebellions somewhere around here. Some people and families will fall out of the elite because they can’t maintain the level of expense that is required. But the outcome as the system moves into crisis phase depends on the cohesion of the elites.

The elites can maintain the immiserised status of the immiserised wage-earners for a long time, provided the elites don’t split. And: there are patterns here.

And every so often, elites do split, and members of the elite then choose to ally with others in society, typically because they fear that outcomes will be worse if they don’t.

(When the venture capitalist Nick Hanauer warned other wealthy people that “the pitchforks are coming”, he is an early sign of a potentially fracturing elite. Climate change may also have the same effect.)

This model has reasonable explanatory power, but (since it was tested with pre-Industrial Revolution data and narratives) it left open the question of whether the model would work in societies that were better able to cushion themselves against adversity. Later work identified that it did still apply.

And at some point, Turchin started referring to this application of statistical analysis of social data and trends as “cliodynamics”. This is how he defines cliodynamics in The End Times:

It uses the methods of data science, treating the historical record, compiled by generations of historians, as Big Data. It employs mathematical models to trace the intricate web of in-tractions between the different "moving parts" of the complex social systems that are our societies. Most importantly, cliodynamics uses the scientific method, in which alternative theories are subject to empirical tests with data (p.xii).

Turchin’s work on both the US Antebellum period and 20th century America also suggested that the model has reasonable value in terms of projecting increases or declines in levels of social tension. (The relevant article is here).

Even if carrying capacity is not always a constraint in more complex societies, institutional and regime factors can have the same effect. For example: In the 1970s, in the UK and the US, wages reached their highest share of national income relative to profits—and we’re still living in the aftermath of the political and economic strategies deployed by capital to bring wages back down again.

That 2013 paper has this version of Structural Demographics in it, which at least explains some of the relationships and data points that sit within the structural-demographic model.

(Peter Turchin, ‘Modeling social pressures towards instability’, Cliodynamics, 2013.)

Associated with this work is an institute (The Cliodynamics Institute) and an open access journal, and a large database that supports their associated modelling work.

But in short, the reason that I think that the model is interesting is that it combines two different systems that matter in human societies. The first is about economics, there are familiar long wave models (such as Kondratiev) that look at this in detail. (I wrote about these here).and are, if anything, becoming more important. The second is about status—humans are status-driven creatures, as we learn in different ways from Rene Girard and Michael Marmot. And on their own neither system really explains our current politics properly.

In the second part, I’ll take a look at End Times.

2: Dark tourism, rich thrills

News is easier to understand when it is familiar. And one of the elements of the submersible story was that it followed some very familiar tropes that are familiar to us both from other news stories and from Hollywood films. The enclosed space, the ticking clock, the rescuers fighting with the technology, and so on.

There’s a reason why these true stories are often turned into films, although it helps if the trapped people are saved.

But my interest here isn’t the media theory. There’s a short piece at the Transforming Society blog that locates the OceanGate Expeditions submersible trip to the Titanic within the wider context of changes in tourism, especially the tourism of the rich. Three of the authors have recently edited a book called 50 Dark Destinations, on crime and contemporary tourism.

(From the OceanGate Expeditions website—parts of which are still up)

It’s a bitty piece, if I’m honest, although I don’t know if that is because it was written quickly or because the four authors were each busy popping in the bits that mattered to them.

But two or three of the ideas that are in the mix seem interesting and more broadly relevant. The first, talking their book, is the prevalence of interest in sites of death as tourist destinations. This is not new, but it is now more visual:

In recent years, the way in which individuals engage with sites of tragedy has changed, reflective of wider changes in consumer tourism patterns. This is perhaps best demonstrated by the mass of tourists each day who are furiously snapping away on their iPhones at Ground Zero, in the middle of Choeung Ek killing fields or on the tracks leading into Auschwitz.

The second is that as the earth becomes more familiar to us, it becomes more and more difficult to do something really unusual on holiday. It’s harder to impress people. One of the consequences of this is that luxury tourism comes with more damage in its wake:

As Oliver Smith argued in 2019, “the drift towards luxury in the tourist industry compounds, exacerbates and perpetuates environmental and cultural harms on a local and global scale”. Within this discussion, he highlights those luxurious forms of tourism, such as private villas and Michelin starred restaurants, are no longer the preserve of the super-rich... Such changes create clear obstacles for the super-rich to display their ‘unique’ identity, forcing the luxury consumer experience to adapt. Within this context, Smith offers the examples of canned hunting, private flights and skiing.

Tourist travels to space—and to the Titanic—come unto this category as well. I’m reminded of a tourism scenario I wrote 15 years ago when I suggested that the rich might pay to do things on private land that would be illegal in public space. And it seems that this being identified as a trend here as well:

(T)he extremity of the experience is seemingly growing ever more risky. As Featherstone observes in his analysis of Marquis de Sade and the sexual libertine, criminal luxury is comparable to contemporary culture. Extreme luxury and criminal transgression are viewed as normal and necessary to the global system, though harmful to those around them. Clear comparisons can be drawn between the extremities of luxury and transgression within Featherstone’s analysis and the contemporary super-rich luxury tourists.

And one of the points they make here—I’ll paraphrase—is that perhaps the risk in the trip was part of the attraction. It’s normally poor people who end up travelling on unsafe equipment. Here the tourists had paid $250,000 for their place. As a Guardian story noted, someone who made a trip on the Titan submersible last year explained that the risks were made very clear as part of the contract:

“You sign a waiver before you get on that mentions death three different times. They’re learning as they go along … things go wrong. I’ve taken three different dives with this company and you almost always (lose) communication.”

I suspect that space tourism has a similar dark underside—a frisson of fear, of being right at the edge—in its attraction to the ultra-wealthy who can afford it.

j2t#471

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.