26 January 2021. Wealth | Australia

The global wealth inequality numbers just keep getting worse. Mixed feelings a long way from home.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

1: The global wealth inequality numbers just keep getting worse

Oxfam has been producing an annual report on wealth inequality for a few years now, timing its publication for when the billionaires it discussed were heading to Davos. The headline has typically been the same: that only (insert small number here) billionaires have as much wealth as 50% of the world’s population. The small number has been getting smaller over time.

And after all, who knew that pumping billions of dollars/ pounds/ yen etc into a broadly stagnant global economy through the banking system would have the effect of creating a giddy rise in asset values?

They’ve moved away from this format a little this year, in a report called ‘Inequality Kills’, to focus on the impact of the pandemic on inequality. Some of these data points are, well, a little constructed. All the same, they’re the sort of numbers that might surprise someone arriving on the planet from elsewhere who hadn’t got used to them yet:

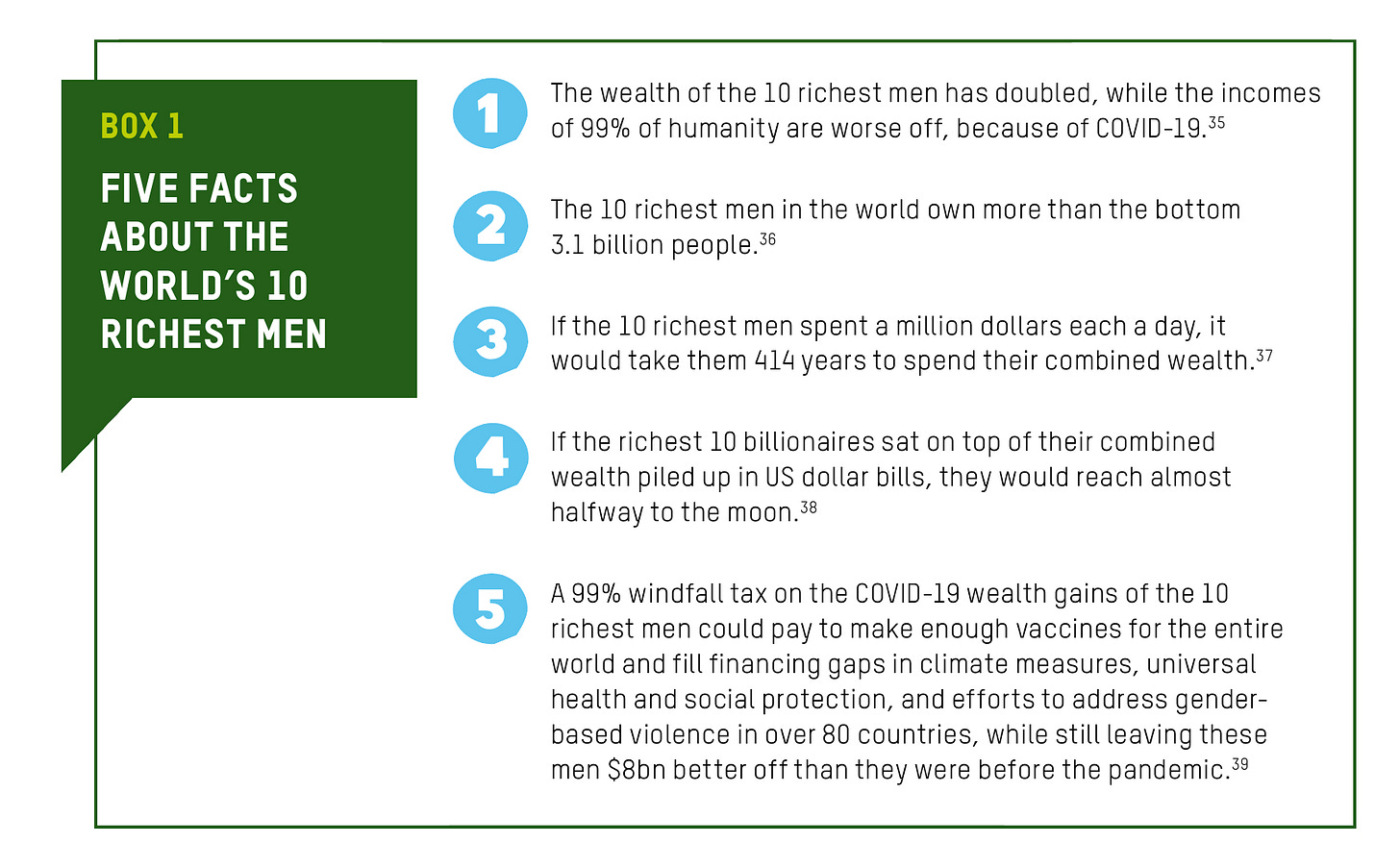

- The wealth of the 10 richest men has doubled, while the incomes of 99% of humanity are worse off, because of COVID-19.

- Inequality contributes to the death of at least one person every four seconds.

- 252 men have more wealth than all 1 billion women and girls in Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean, combined.

- Since 1995, the top 1% have captured nearly 20 times more of global wealth than the bottom 50% of humanity.

- Twenty of the richest billionaires are estimated, on average, to be emitting as much as 8,000 times more carbon than the billion poorest people.

- 3.4 million Black Americans would be alive today if their life expectancy was the same as White people’s. Before COVID-19, that alarming number was already 2.1 million.

As the Disney heiress Abigail Disney says in a foreword, there’s not much that’s ‘natural’ about such outcomes: they’re the result of choices made about the political and economic system—choices which can be made differently:

Decades of coordinated assault upon the laws, regulations, and systems that protected the common person from those that would exploit them have left us with a hobbled civil society, a union movement on life support, and a government so starved for resources it is barely able to simply collect the taxes it needs just to keep operating... Systemic issues require systemic solutions, not piecemeal attempts at treating symptoms rather than the disease itself. The answer to these complicated problems is ironically simple: taxes.

And to underline this, the report includes a staggering chart on changes in shares of wealth since 1995. This is an extreme version of Branko Milanovich’s ‘elephant’ chart which shows growth or decline in income at different percentiles of global polulation.

(Source: Oxfam, ‘Inequality Kills’)

There’s more on the effects of different forms of inequality, which is a useful reminder of the deep forms of structural violence that inequality creates. I’d have liked to see something on the impact on our democracies and public institutions, in a world where something like 10% of the world’s wealth is ‘lost’ offshore, and the extremely rich are able to block laws that inconvenience them.

But it’s perhaps more useful to look at the remedies that the report suggests, with the idea that social movements might influence change. One of the unhelpful ideas that has been killed off by the pandemic is that governments have no power in a globalised world, which at least creates a small lever.

They recommend some specific innovations that could make a difference to inequality:

(1) Using progressive fiscal instruments to invest in ordinary people rather than shore up bank balance sheets and asset values. This would need to be couple with debt reduction—or write-offs—for poorer countries.

(2) 'Solidarity taxes’, to claw back the huge gains made by the extremely wealthy during the pandemic. The numbers here are huge:

By way of illustration, a one-off 99% emergency tax on new, pandemic-era billionaire wealth of just the top 10 richest men alone would raise $812bn. These resources could pay to make enough vaccines for the entire world and fill financing gaps in climate measures, universal health and social protection.

And governments across the world have done this before, for example after the Second World War.

(3) Directing that money to schemes that are known to reduce inequality. This would include: investment in health systems that are free at point of use; social protection that provides income security; funding climate adaptation; and investment in reducing gender violence. This last is obviously a good thing in its own right, but is also known to improve social and economic outcomes more generally.

(4) ‘Pre-distribution’ to shift power and income in the economy.

Policies, systems, and laws that actively tackle the extreme capture of wealth and income by the richest in society are vital. Oxfam proposes actions which would help ensure that the gains of the market, the private sector, and globalization are more assertively directed into the hands of workers and ordinary people. We also propose changes to laws and representation that are overly skewed in favor of the richest countries, corporations, and individuals.

These include actions to reduce inequality between rich and poor countries, such as intellectual property waivers; to reduce inequality between workers and owners, such reinforcing social and related rights; to reduce gender inequality; and to reduce economic inequality; and broadening political representation.

Of course, it’s easier to imagine the end of the species than it is to imagine dismantling neoliberalism. But what we know about policy making (this is the ‘garbage can model of policy making’) is that when policy fails, or crisis strikes, policy makers reach for whatever is lying about to try to fix things. So it’s useful that Oxfam takes the trouble to leave these progressive policy proposals lying around. Just for when that moment strikes.

(Source: Oxfam, ‘Inequality Kills’)

2: Mixed feelings a long way from home

Obviously there are two views of Australia Day. One person’s rapacious and racist colonial assault is another person’s new opportunity.

Which is another way of saying I liked a short post on the blog of the London Review of Books shop, in London, by an Australian member of the cafe staff, that marked the day by writing about these powerful mixed feelings when you’re living and working 12,000 miles away from where you grew up. (The post acknowledges the difficulties of the idea of ‘Australia Day’.)

Every time I return home to Australia, I gather native botanicals and bring them back to London to bake with, or drink as tea. One of my favourites is lemon myrtle, with its sunburnt kiss aroma – I love to use it in combination with kumquat jam. Big kumquat shrubs are dotted around the older neighborhoods of Melbourne, along with passion fruit vines and persimmon trees. Eucalyptus, bay, lemon – in a blink of an eye, these flavours take me 9000 miles from Brixton back to where I grew up.

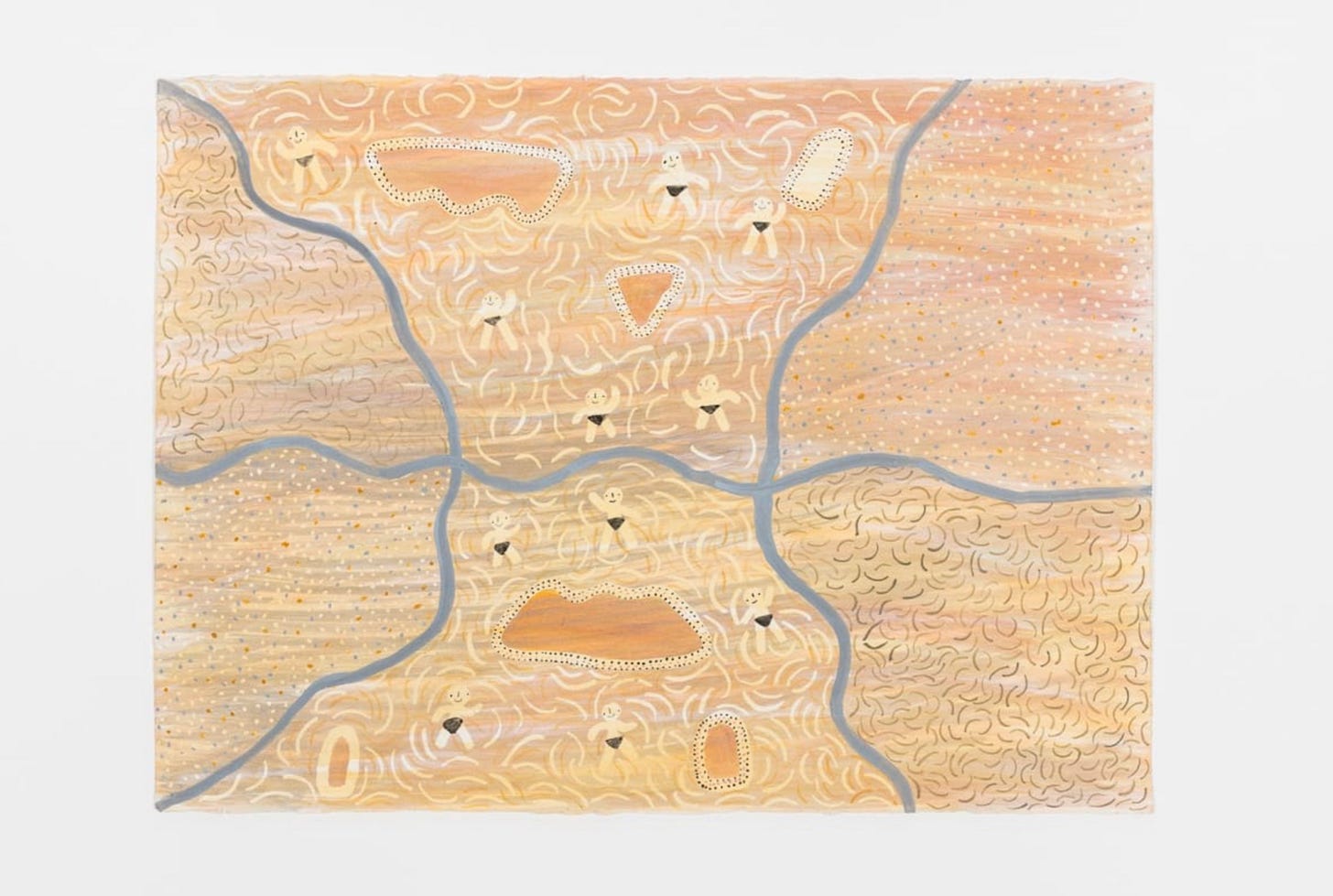

In the author’s case, one thing that triggered her sense of being away was a picture she’s seen in the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition. ‘Keep River’, by Peggy Griffiths, is named for Keep River National Park in northern Australia:

Her work documents the traditional country of her mother and grandfather, and celebrates her Miriwoong culture. In an interview, she speaks of how her childhood was shaped by the influence of her elders, and of her memories of seeing these same elders taken away from their camp in chains.

Griffiths herself, according to her gallery biography, “was hidden once when Welfare came so that they would not take me away.”

(‘Keep River’, by Peggy Griffiths. Courtesy of the JGM Gallery)

Those of us who have had the benefit of empires all carry our burden of shame. As the writer acknowledges:

It can be hard to reconcile a deep personal bond with a place with the tragedy of its history. My way of acknowledging this love and sadness from afar is to connect with my own memories through baking, and with the Aboriginal custodians of the land through literature and reading.

And for the next few weeks—for those who can get to central London—apparently the LRB Cake Shop will be serving lemon myrtle cookies with eucalyptus tea. Some recent books by Aboriginal and BIPOC writers, recommended in the piece, are available in the shop next door.

j2t#251

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.