26 April 2024. Climate | Film

The losses caused by climate change will be huge // Inventing the rom-com, 90 years ago. [#564]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open. Have a good weekend!

1: The losses caused by climate change will be huge, says Nature

One of the problems with discussing dealing with climate change is that sooner or later you run into discussion about what it will cost. This is usually over-estimated in practice, because the money that we’ll spend anyway on infrastructure is overlooked.

So paying for the transition is partly about making sure that we stop spending money on infrastructure that reinforces fossil fuel systems, and spend that on post-carbon infrastructure, which is why one of the critical political and economic fights here is about getting banks to stop investing in new oil and gas.

But the other assumption that is always made—especially by those who remain climate-sceptic, even if just through their behaviour—is that somehow there’s a zero cost attached to doing nothing. Even the lightest investigation into the impact of warming shows that there will be costs attached to it.

So this is a way to note both the recent article in Nature that suggests that climate change will have costs of $38 trillion a year to the world economy by 2050, and Bill McKibben’s commentary on it. When I see numbers like $38 trillion I’m reminded of Gil Scott-Heron’s song ‘I’m New Here’:

She said I had an ego on me

The size of Texas

Well, I'm new here, and I forget

Does that mean big, or small?

So, $38 trillion. Does that mean big, or small?

It means big. As Bill McKibben explains,

The entire world economy at the moment is about $100 trillion a year; the federal budget is about $6 trillion a year. $38 trillion is 150 Bezoses (which is sick in its own way). If those numbers seem impossible to comprehend, then let Bloomberg break it down for you, “planetary warming will result in an income reduction of 19% globally by mid-century, compared to a global economy without climate change.”

The Nature study is apparently the largest of its kind. It’s been led by the Potsdam Institute in Germany, and informed commentators have described it as more “granular and empirical” than previous assessments of this kind. It also concludes that these losses are already locked in, because of existing emissions. The study looked at data from 1,600 regions worldwide.

They find, perhaps unsurprisingly, that the cost of mitigation is far less than the scale of the losses.

We compare the damages to which the world is committed over the next 25 years to estimates of the mitigation costs required to achieve the Paris Climate Agreement... we find that the median committed climate damages are larger than the median mitigation costs in 2050 (six trillion in 2005 international dollars) by a factor of approximately six.

McKibben quotes James Murray, the editor of Business Green, who had a bit more of the detail:

"Strong income reductions are projected for the majority of regions, including North America and Europe, with South Asia and Africa being most strongly affected," said PIK scientist and co-author of the study, Maximilian Kotz. "These are caused by the impact of climate change on various aspects that are relevant for economic growth such as agricultural yields, labour productivity or infrastructure.

At his Carbon Commentary newsletter, Chris Goodall noted,

These costs are a many times multiple of the costs of decarbonisation, says (the Potsdam Institute). The estimates also seem to exclude the impact of rising sea levels, which would increase economic losses even further. Economic damages in the PIK model are even higher in lower income countries such as Brazil, parts of West Africa and Pakistan.

The Nature article also lists a number of other potentially adverse climate-related issues that are outside of their economic impact estimate because they are difficult to model reliably:

Important channels such as impacts from heatwaves, sea-level rise, tropical cyclones and tipping points, as well as non-market damages such as those to ecosystems and human health, are not considered in these estimates.

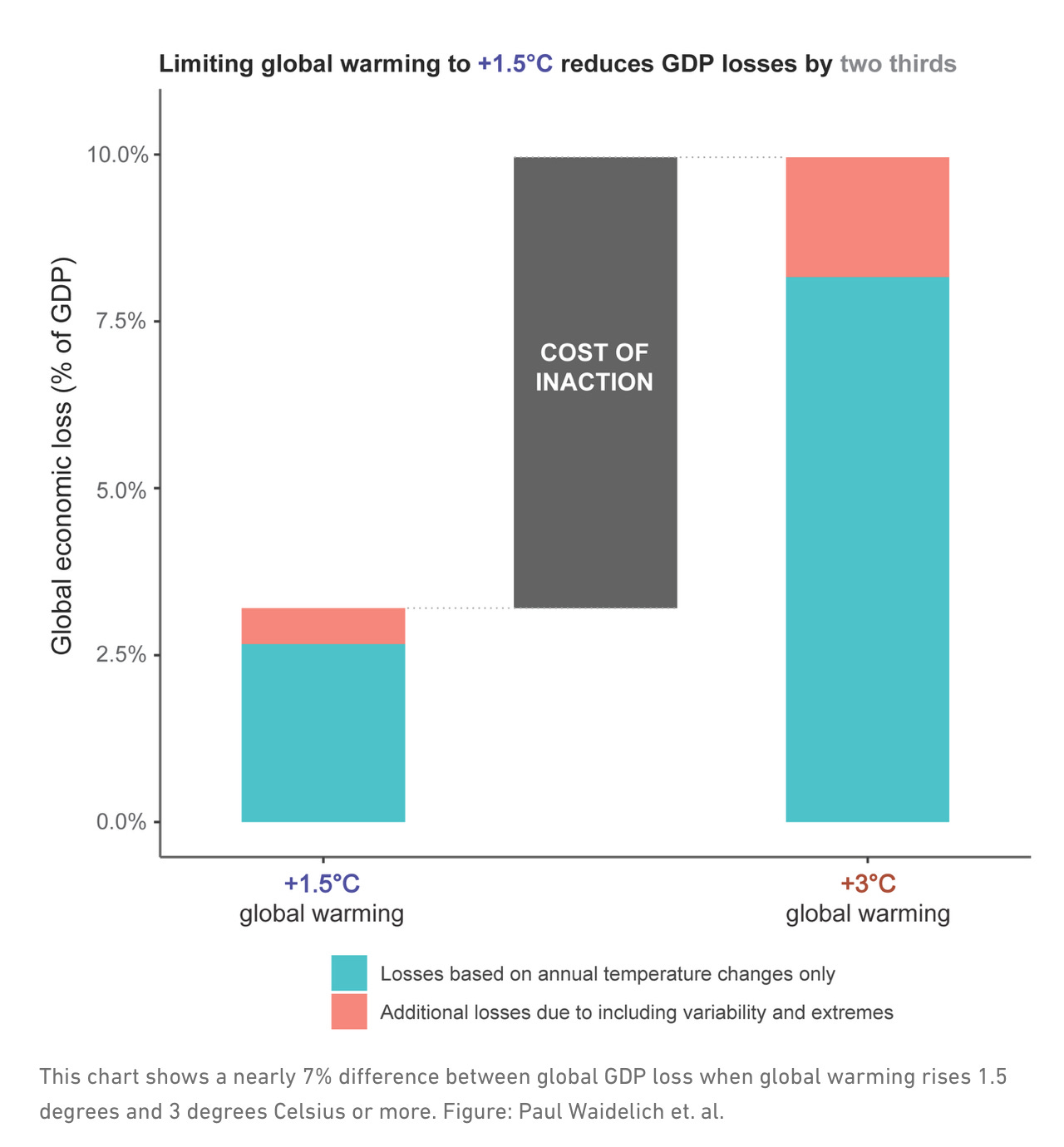

Chris Goodall also notes a recent similar study by the Swiss institute ETH Zurich, whose headline numbers are lower—but not a lot lower. The ETH work looked at 33 different climate models. ETH

has lower estimates of lost global income at 10-12% assuming a 3 degree temperature rise above pre-industrial averages. As with the PIK work, the economic costs are forecast to be far more severe in lower income countries.

Looking at ETH’s summary of their research, the researcher Paul Waidelich points out that the spiking effects of temperature change caused by climate change has larger effects on economic output than has previously been assumed:

"If we take into account that warmer years also come with changes in rainfall and temperature variability, it turns out that the estimated impact of spiking temperatures is worse than previously thought," explains doctoral researcher and economist Paul Waidelich. "Therefore, omitting variability and extremes risks underestimating the damage of temperature changes."

The difference between 3 degrees and 1.5 degrees is significant—and as with the Potsdam study, the cost of climate mitigation is far lower than the cost of damage, as an ETH Zurich chart shows. But: it’s worth noting that there are economic losses even at 1.5 degrees.

(Source: ETH Zurich)

The first thing I thought of when I saw this headline was The Limits to Growth base case scenario, which the world has been tracking depressingly reliably since the 1970s. That projected declines in industrial production in the 2020s and declines in world population in the 2030s. Of course, this projection was monstered at the time, often in bad faith. McKibben’s mind went there as well:

We thought about it as a society and then, with the election of Ronald Reagan, rejected it; we are now harvesting that bitter fruit. If we don’t act now then our children may wish they still had bitter fruit to harvest.

And McKibben’s other point is just about how short-termist capitalists are being right now—I guess on Chuck Prince’s famous and completely self-destructive principle that if the music is playing, you have to keep dancing:

As Exxon’s CEO helpfully explained earlier this year, it’s not that you couldn’t make good money from renewable energy—you just couldn’t make ‘above average returns’ because sunshine is free. So instead we’ll tank the world, and with it the world economy.

If we’re already locked in to these losses, is it worth doing anything? Well, yes. The Nature researchers say that the costs of climate change diverge sharply beyond 2049, depending on the climate path. It’s also worth noting that the impact of all of those factors they haven’t quantified get sharply worse as climate worsens.

One of the policy implications for me here is that we might just have to pay the fossil fuel companies to stop producing oil. I may come back to this in the next few weeks.

2: Inventing the rom-com, 90 years ago

It Happened One Night—released ninety years ago—is, famously, the first of only three films to sweep all of the five of the big awards at the Oscars: best film, best director, best actor, best actress, best adaptation. Yet it was made in a hurry, and neither of the leads thought much of it when they had finished shooting. Despite this, it set the template for the rom-com, and also paved the way for the screwball comedy.

(It Happened One Night: Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert, down on their luck and right out of money).

If you haven’t seen it, here’s the plot in a nutshell. The heiress Ellen Andrews (Claudette Colbert) is being held by her tycoon father on a yacht in Florida after a runaway marriage to a playboy. She escapes by swimming for the shore and makes for the night bus to New York. The newspaperman Peter Warne (Clark Gable) spots her and sort of takes under his wing. This is just as well, as she has her bag stolen at the first stop. Meanwhile, her father has put a reward out for her and has private detectives on her trail.

To give a flavour, here’s the “meet cute”, as it certainly wasn’t called in 1934:

At first the relationship between Andrews and Warne is purely transactional. She needs to get back to New York, he needs the story. She’s other-worldly, he’s a prickly and irascible know-it-all.

Of course, once on the road (and since then you’ve seen this film a thousand times), intimacy grows. Not sexual intimacy, because this is 1934 and the Hays Code is about to be introduced, but emotional intimacy. She’s smarter, and funnier, than she looks, and more reflective, and he is less hard-boiled than he lets on.

But perhaps most importantly, life in Depression America washes all around it. In a piece that the British film magazine Sight & Sound re-published to mark the 90th anniversary Kate Stables suggests that the reason that the film has lasted as well as it has is because, for all the she is an heiress, she has no money, and he doesn’t have much. This makes for some tough choices. (Small disclosure: Kate Stables and I co-wrote several articles about “new media” back in the 1990s, when digital media was still “new”).

Frank Capra had told the Hollywood newspaper Variety in 1932 that “someone is going to evolve a great film out of the Depression”. He had several attempts at this, most of them rather more portentous than It Happened One Night, his second try. As Stables says:

It’s a road-trip masquerade about playing poor, where real life breaks in via road thieves and starving bus passengers, where a dollar has to stretch and shunning a scavenged carrot is a sin. Perhaps it’s the only sin in this movie, which is constantly playing with the idea of transgression in cohabitation or adultery, but which otherwise obeys Capra’s maxim: “There are no rules in filmmaking. Only sins. And the cardinal sin is dullness.” In fact if anything the film’s sparkling qualities... have kept us from seeing what a tough little cookie it is.

Of course, there’s a series of misunderstandings along the way that separate the couple, and a satisfying and amusing ending. Give the audience what they want, but not in the way they expect it, as a screenwriter I once worked with told me.

No-one could have been more surprised by It Happened One Night’s Oscar successes than Claudette Colbert. She wasn’t the first choice for the part, and she had had a bad experience previously working with the film’s director, Franck Capra. She agreed to do the film on condition she was paid twice her usual fee, and provided her shooting schedule was only four weeks. And afterwards, according to Wikipedia:

After filming was done, Colbert complained to her friend, "I just finished the worst picture in the world."

She skipped the Oscars ceremony to head off on holiday, but hadn’t left town when Columbia, the studio, learned that she had won. She collected the award in her travel clothes.

Actors are often poor judges of the films they make. They don’t usually see the rushes, and they don’t see what goes on in the cutting room. In this case, Colbert and Gable were also dissatisfied with the initial script, and the screenwriter Robert Riskin was re-writing as they were filming. But there may be something else going on here. It Happened One Night effectively invented a new genre. There’s also a lot of script for what’s still a relatively early talkie (the first part-talkie film, The Jazz Singer, was released in 1927.)

The reason we have genre is to help people make sense of cultural forms, so to help Claudette Colbert out here, it’s possible that she simply didn’t recognise the picture she had just made because it didn’t fit into a recognisable genre. She had nothing to judge it against. The studio didn’t have that much confidence either; the advertising budget was low, and it opened in a small number of cinemas. But the reviews were good and audiences found the film and they liked it, despite this.

The reasons the film succeeded: well, first, it’s funny. I went to see it recently in a cinema in its new digital print, and 90 years later the audience was laughing, sometime out loud.

Secondly, as suggested above, it plays with sex all the way through without ever crossing the kind of line that the studio would have found problematic.

Inevitably, Andrews and Warne end up having to share a room together. Of course, she suspects his motives, but he is (rightly) offended. His behaviour is completely proper, even if he has to undress to the waist, completely ostentatiously, to get her to retreat to her side of the blanket that he has hung across the room for the sake of modesty. (And actually, the clip above ought to run a bit longer.)

And third, it’s tougher than your typical rom-com, as Stables suggests:

The romance comes late, after real and imagined dupings and betrayals, and the narrative mercilessly mocks the idea of “a perfectly nice married couple” in Peter and Ellie’s shrieking pantomime of white-trash marital bliss, put on to evade her father’s detectives.

And compared to this original version, contemporary rom-com is as soft as mush, a series of contrivances designed to reproduce a formula. Even though, in our hard times, audiences might quite like something a bit more hard-boiled.

UPDATE: Wealth and climate

You write a couple of posts about wealth and of course, you have primed yourself. But something is going on when a Nobel Prize-winning economist proposes that a tax on billionaires should finance climate reparations.

The proposal was made by Esther Duflo to a G20 meeting last week, according to Heated. Here’s a couple of extracts:

Duflo estimates that the U.S. and Europe alone inflict more than $500 billion per year in climate damages on low- and middle-income countries... The climate taxes would not replace the United Nations’ loss and damage fund, which will help poorer countries recover from climate disasters. But asking rich countries to voluntarily send money to poor countries has not historically worked…

Duflo proposes increasing an existing international tax on multinational corporations from 15 percent to 20 percent. There would also be a 2 percent wealth tax on the world’s top 3,000 billionaires. The two climate taxes combined could raise up to $400 billion per year for a “loss, damage, and adaptation fund”.

Duflo also suggests sending this money directly to the people directly affected by climate change, which is also a departure. The Loss and Damage Fund is currently managed by the World Bank, who seem to see it as a cash cow (yes, satire is dead).

j2t#565

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.