26 April 2023. Health | Software

We are getting more emotionally distressed // Software didn’t eat the world.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: We are getting more emotionally distressed

Emotional distress is increasing—steadily, and across many countries. An article in BigThink reports on an analysis of Gallup data across scores of countries that comes to this clear conclusion.

Gallup asks this question in many of its surveys:

“Please think about yesterday, from the morning until the end of the day. Think about where you were, what you were doing, who you were with, and how you felt.”

They’ve also been doing this since early in the 21st century, so we have data that is both longitudinal and geographically broad. The dataset now totals 1.5 million responses across 113 countries, and two psychologists—Michael Daly from Maynooth University in Ireland and Lucía Macchia from the City University of London in the UK—have trawled this data.

(Edvard Munch, of course. CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication)

In a paper recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Daly and Macchia reported:

“The prevalence of feelings of distress rose from 25.16% in 2009 to 31.19% in 2021, an overall increase of 6.03 percentage points.”

Daly and Macchia detailed how they arrived at that result. The duo analyzed this dataset of responses from 1.5 million adults in 113 countries; they used data only from nations with statistics from a majority of the conducted survey waves, ensuring consistency and completeness. A person was considered to feel emotional distress if they reported experiencing a lot of stress, worry, sadness, or anger the prior day.

The overall increase hides some striking—if predictable—social data.

The first thing to say is that although there was a spike in the data for the pandemic, it seems have gone back down surprisingly quickly.

In terms of age, although 35-54 year olds are more likely to share signs of distress, the biggest increase is among those under 35. Women are more likely to be distressed than men. Those with the worst education have seen the biggest increase in distress (this is global data, so includes people who have only elementary education. Similarly, levels of distress correlate inversely with income quintiles.

But overall: all these numbers are going up.

The researchers don’t speculate on the causes of this, but the BigThink writer Ross Pomeroy has a go:

Since roughly 2009, headlines of stories in popular media have grown increasingly negative. Denotations of anger, fear, disgust, and sadness in headlines have jumped sharply, according to an analysispublished last fall. Couple this trend with the rise of social media, where news is readily viewed and rapidly shared, and you have a recipe for rising emotional distress.

There is other data that seems to point in the same direction.

The CDC’s most recent Youth Risk Behavior Survey, released earlier this year, highlights similarly concerning trends. A standout is that 57% of high-school girls in 2021 reported experiencing “persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness” during the past year, an increase from 36% in 2011. (The survey didn’t explore potential causes, though some psychologists point to social media).

That last link goes to the work of Jonathan Haidt, and he had an hugely long article on his newsletter in February this year basically arguing that this increase was down to the combination of a wide social trend, which is a change in the nature of childhood experience around play, and a narrower but deeper one, to do with smartphones and social media. He connects these two factors.

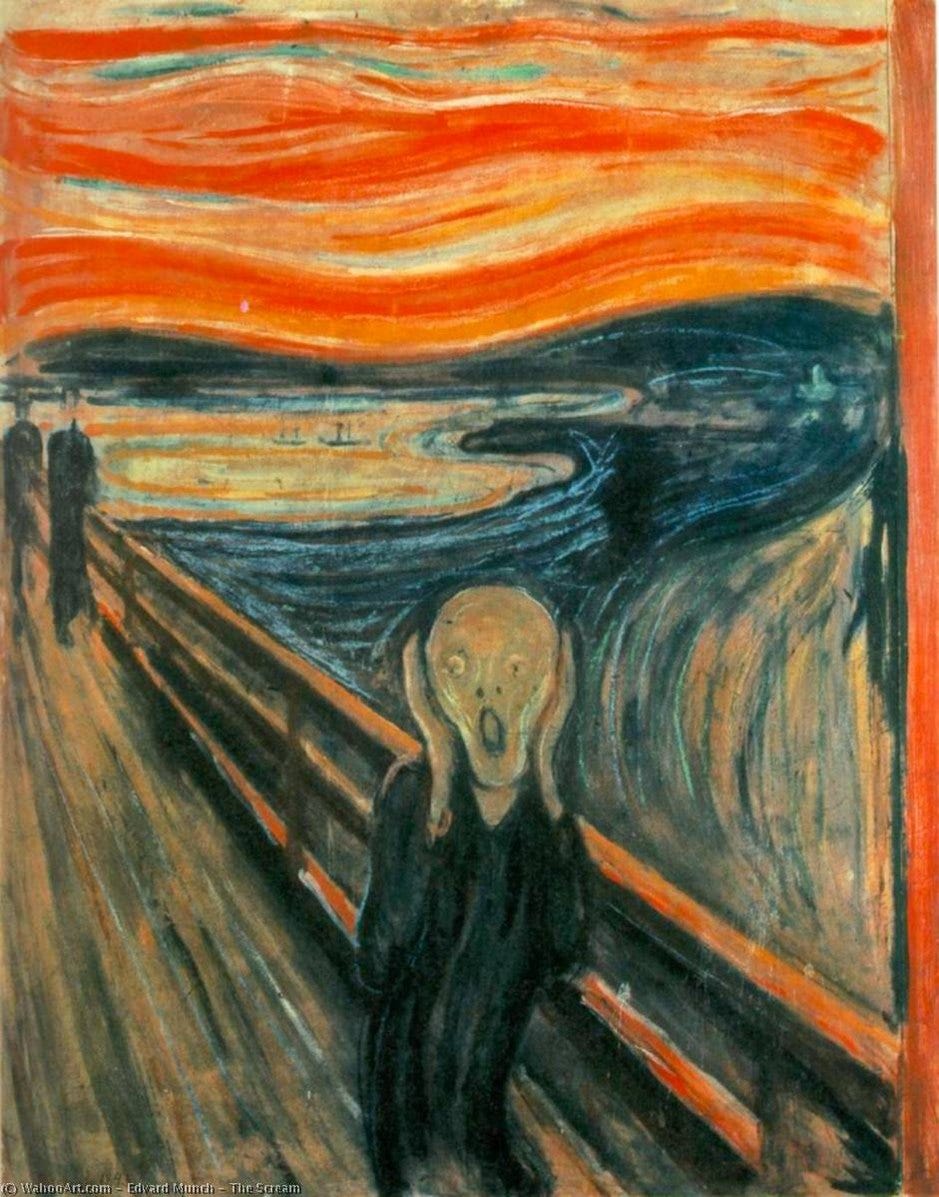

He has a striking chart based on a large UK survey:

(Percent of UK adolescents with “clinically relevant depressive symptoms” by hours per weekday of social media use, including controls. Haidt and Twenge created this graph from the data given in Table 2 of Kelly, Zilanawala, Booker, & Sacker (2019), page 6.)

Of course, it’s possible that correlation isn’t causation, because you could imagine that heavy social media use is an outcome of depression as much as its cause. Anyway, there’s way, way, too much in that article to go into here, but here’s a couple of short extracts to try to represent his argument:

On play:

the transition from a play-based childhood involving a lot of risky unsupervised play, which is essential for overcoming fear and fragility, to a phone-based childhood which blocks normal human development by taking time away from sleep, play, and in-person socializing, as well as causing addiction and drowning kids in social comparisons they can’t win.

And here’s the argument on why phone-use is more influential despite studies which show only small effects:

Nearly all of the research––the “hundreds of studies” that Hancock referred to––have treated social media as if it were like sugar consumption... But social media is very different because it transforms social life for everyone, even for those who don’t use social media, whereas sugar consumption just harms the consumer.

But, but, but: it’s possible that excessive use of social media is bad for your mental health, for lots of obvious reasons (humans are status-seeking creatures with powerful mimetic effects).

And as an ex-journalist, I’m also willing to believe that news is bad for our mental health (that’s what I tell my wife, anyway).

But there are also reasons why the news has got worse over the last decade that aren’t self-servingly about chasing clicks. Haidt doesn’t discuss whether climate change might have an effect on teenaged health, for example.

And certainly the people who seem to have the most evidence of emotional distress in the Gallup data (low income, poor education, women) are also the least likely to own smartphones.

We’re talking about different datasets, of course, as I’m sure people will remind me. But they seem like they are probably connected. More research required.

2: Software didn’t eat the world

The technology writer Timothy B. Lee has a piece on his newsletter looking back at the claim made in 2011 by Marc Andreesen in an influential essay. “Software”, he said, “is eating the world”.

Andreessen, co-founder of the venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz, argued that the software revolution was only getting started. “In many industries, new software ideas will result in the rise of new Silicon Valley-style start-ups that invade existing industries with impunity,” Andreessen wrote. “Companies in every industry need to assume that a software revolution is coming.”

It was probably a combination of Silicon Valley hype and talking up the value of his software company investments.

It didn’t stop there. In 2013, Andreesen also thought that cryptocurrency was going to eat the finance system:

But the point is: it didn’t happen. There is a number of reasons for this. Lee is interested in whether the non-barking dog that is software’s failure to eat the world has lessons for us as we deal with a similar wave of bullish projections about Large Learning Models and AI.

But let’s go back first to what hasn’t happened:

The venture capitalists who poured billions of dollars into startups... during the 2010s expected some of them to eventually be as big as Google or Facebook. After all, they thought, industries like hospitality, transportation, and finance are huge. The rewards for disrupting them should be correspondingly large... Computers and smartphones have become ubiquitous across the economy. But this has led to only modest changes for established industries like health care, education, housing, and transportation.

Lee thinks this is down to a persistent blindspot in the way that Silicon Valley thinks about the world:

a tendency to overestimate the power of information technology and underestimate the complexity of the physical world.

He’s gone back and looked at the startups that have done best over the last 12 years. They include a number of businesses that have simplified the finance world (companies like Stripe and Venmo, rather than cryptobusinesses such as Coinbase) and, beyond that, probably Airbnb and Uber, although even Uber is struggling with margins and profitability despite its scale.

In a long article, Lee walks this out to the types of future in which humans are also using AI in their work.

Maybe these are obvious points, but there’s a whole lot of areas where human interaction matters, whether it’s plumbing or social care. And he reminds us that Starbucks had to tell its baristas not to make multiple coffees at the same time because it irritated customers, who expected personal service.

We also have quite a lot of experience of what happens in sectors when parts of them are automated, since this has been happening since the 1980s (from memory David Autor has argued that this had as big an effect, downwards, on wages in the 1990s as did China/globalisation). Sometime, as in banking, jobs move around—fewer bank branch tellers, but more people in the call centre. The attempts cotinue to quantify this:

A recent paper by computer scientist Ed Felten, business professor Manav Raj, and economist Robert Seamans looked at a database of occupations and tried to define how “exposed” each job was to large language models like ChatGPT. They did this by breaking each job down into 52 human abilities (things like “oral comprehension, oral expression, inductive reasoning, arm-hand steadiness”) and then estimating how well AI software could perform each of these tasks.

Telemarketers topped the list; judges were quite high up. So were clinical psychologists.

(Judge at work. Creative Commons image by Wannapik).

This probably ought to be a reminder that economists and computer scientists shouldn’t be allowed out together to discuss the future of work. Frey and Benedikt, the authors of the wild projection a decade ago that 47% of jobs were at risk from automation, have spent the last ten years explaining why their paper didn’t mean what it said, for example.

Because I am imagining that it’s going to be hard to have trust in a legal system where the judges are automated, just as people still prefer to know that there’s a pilot in the cockpit even if the plane spends most of its time on autopilot. And imagining that clinical psychologists are just running a process, and there’s no affect involved in the engagement with the patient is, well, naive.

But the one finding in this research that might prove interesting: the researchers found a strong positive correlation between language model exposure and income, meaning that higher-wage occupations are more likely to be impacted by AI:

it’s very possible that AI technology will narrow the large wage premium that opened up between college graduates and less educated workers in the late 20th century.

I’d say that Lee underestimates the effect that the internet has had on everyday life over the last 20 years, as it happens, but a lot of that impact has been in the back office, not the front office. That’s probably what will happen with the judge as well: the software will be in his chambers, not on the bench. (Chess is the model here).

As for Andreesen: it could have been his financial interests talking, but I think he actually made the mistake at looking at the third quarter of an S-curve and thinking it was a sign of exponential growth.

j2t#450

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.