25 February 2023. Nationalism | Art

Tom Nairn and the power of nationalism. // Hockney all around.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open. And have a good weekend!

1: Tom Nairn and the power of nationalism

I only realised this week that the great Scottish political theorist Tom Nairn had died at the end of January, at the age of 90. The Scottish writer Gerry Hassan assessed his large legacy in an article in The Scottish Review. Hassan, a friend of Nairn’s, reminded us that Nairn had been influential over a long period of time in a whole range of political debates: about the nature of Britain’s politics and constitution, about Scotland and indepoendence, and more broadly about notions of nationalism:

Nairn's great magnum opus was The Break-Up of Britain, first published in 1977, and which went through four editions: the third published by myself in 2002, the last in 2021 with a foreword by Anthony Barnett. Subsequent books such as After Britain: New Labour and the Return of Scotland (2000) and Pariah: Misfortunes of the British Kingdom(2002) updated his critique of what he called 'Ukania', while The Enchanted Glass (1988) located monarchy as central to the creation of 'the glamour of backwardness' which offered protection to the undemocratic, unreformed state and political system.

(Image: Verso Books)

The 1977 date of The Break-up of Britain marked the year of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee, and perhaps the book and the Sex Pistols’ song are two ends of the same cultural strand. The idea that Britain still remains in part a feudal state, because it had an incomplete revolution, is from Nairn’s work. The rising bourgeoisie was accommodated within the pre-democratic framework of the 17th century. (Another version of this is that England had had a revolution—in the mid-17th century—but it had it too early.) But the same tension was seen in the post-war period, when the Labour party tried to make progressive change possible but constantly bumped into the limits “of a political order built to maintain privilege, inequality and deference”:

The British state today is still characterised by backwardness, its reactionary nature and anti-democracy. As Nairn put it, the monarchical state has been used to incorporate the forces of progress in the 20th century and tame them, then to act as a catalyst for the reconfiguration of power, which happened in the latter half of the 20th century and early 21st century, and which has deformed society, life chances and opportunities.

Nairn’s analysis also put the tensions between the different countries in the United Kingdom, and the dominance of England within it, at the heart of his analysis. In the 1970s, when others were looking at political economy, he was noting the multi-national nature of the UK, with emerging forms of cultural difference in Scotland, Wales, and the north of Ireland at odds with the increasingly right-wing English nationalism of Enoch Powell and then Margaret Thatcher:

He presciently argued that this latter force would increasingly unbalance the union and define itself in opposition to the increasingly integrationist European project. This acute, penetrating analysis has been confirmed in subsequent decades, and still has relevance to the future of the UK.

(Tom Nairn at 80. Photo: Open Democracy)

His approach to Scottish nationalism was also influential. He was critical of early expressions of nationalism, which he saw as being about reaction and anti-progress. However, as forms of nationalism in Scotland evolved, taking a long view, he identified its expression as being part of a modern national identity rather than it looking backwards to 1789 and 1848. He called this ‘neo-nationalism’. Some obituarists have suggested that the current SNP, with its inclusive place-based nationalism connected to a progressive politics, is a reflection on Nairn’s perspective. Hassan has a more nuanced view:

Nairn noted the evolution of a more confident, progressive, pro-European SNP in recent decades; in particular under Alex Salmond's period as First Minister. But he would have noted in Nicola Sturgeon's near decade as First Minister the return to a politics of closure, control and not opening up, trusting others or building popular alliances.

At the same time, the controversy over leadership candidate Kate Forbes’ remarks about equal marriage reflects this sense of a progressive nationalism that Nairn championed in his writings.

Over at New Left Review Perry Anderson assessed Nairn’s legacy, bracketing him with the American radical Mike Davis, who also died recently. Nairn’s radically different view of British politics was partly due to the years he spent in Italy in the 1950s, speaking fluent Italian and studying the work of the Italian theorist Antonio Gramsci. A long series of articles in New Left Review paved the way for both The Break-Up of Britain and an earlier book, The Left Against Europe?

In the course of this sequence, he rallied to the national cause in Scotland, and opened out his range beyond Ukania, as he would later call it, to a worldwide theory of nationalism conceived in the image of a ‘Modern Janus’—an effigy looking both backwards and forwards, to the past and to the future—which it had been Marxism’s great failure never to understand. The turning-point of the twentieth century had been 1914, rather than 1917: not class but nationality was the motor of modern history.

In his later writings, after the end of the Cold War, he concluded that nations were “the fundamental vectors of democratic emancipation.”

The growth of a democratic nationalism, no longer ethnic but civic in outlook, was the deep underlying trend of world history since the Second World War, and offered the best hope for humanity.

This didn’t go so well after 9/11, and Nairn thought that the United States “had hijacked globalization” for reactionary ends, helped by the UK. But he also saw a fundamental conflict between nationalism and neoliberalism:

the Anglo-American attempt to ‘cram the genie of democratic nationalism back into the neo-liberal bottle’ had provoked ‘a gathering storm of resentment and shame’ against it, and would fail. The only site of collective agency capable of developing a credible alternative to neo-imperialism and neo-liberalism, wrenching the world free of their iron maidens, was the nation-state.

Obviously he was right about this, but this plays out in different ways. Orban and Modi are also alternatives to neo-imperialism. Nationalism looks both ways.

And one thing that came to my mind, reading these two articles and other obituaries, as we watch the anniversary of the Russian attack on the Ukraine, is that we are watching a war between competing versions of nationalism, the reactionary and the civic. Nairn has been ill for some time, but I was intrigued to find that a month into the war James Meek had made a similar comparison, likening post-2014 Ukraine to Nairn’s description of Scottish aspirations to “a new interdependence”.

If you want to read more of Nairn’s thinking without having to read his books, his publisher Verso Books posted a substantial and academic article by Nairn from The Break-up of Britain, written in the 1970s, on “the twilight of the British state.”

2: Hockney all around

I went to see the David Hockney ‘Bigger & Closer (not smaller and further away’ at Lightroom in London this week, and realise that I don’t know what the generic name is for this. (It’s billed as an ‘Experience’). But as a friend said to me before I went, these things are popping up all over the place, so it’s probably only a matter of time before they get an neologism of their own.

These things: an artist’s work condensed into an audio-visual show, in a big space, showing on four walls simultaneously with a carefully designed sound landscape. I went to see the Van Gogh equivalent in London a couple of years ago, and was pleasantly surprised. Since Hockney is still alive, and had been interviewed, as well as being involved in the three-year production process, it functioned as a kind of three-dimensional retrospective. The director is Nicholas Hytner, once of the National Theatre.

Big space: I’m estimating here, but probably about 15 metres wide by 25 metres deep by 12 metres high. A piece in the Guardian had some other data:

the show features 1,408 loudspeakers, 28 projectors and a digital canvas size of approximately 108m pixels.

The programme plays for 50 minutes, although the ticket is clear that you can stay on longer if you want to. This is a bit of a throwback to pre-war cinema, when people would arrive in the middle of a film and stay until they got back to that point in the show (and sometimes had to be reminded to leave).

Because there’s images on all four walls most of the time, it’s hard to find the optimal viewing point. One man near to me solved this by strolling around in the middle of the (slightly crowded) space. I’d missed something behind me when I first arrived, so swapped over to the other side of the space to watch it from a different perspective.

I wrote about Hockney’s views on art and photography when I visited last year the Fitzwilliam exhibition in Cambridge that he had curated. Some of this was a reprise of that, but narrated in his engaging Bradford accent and with bigger images.

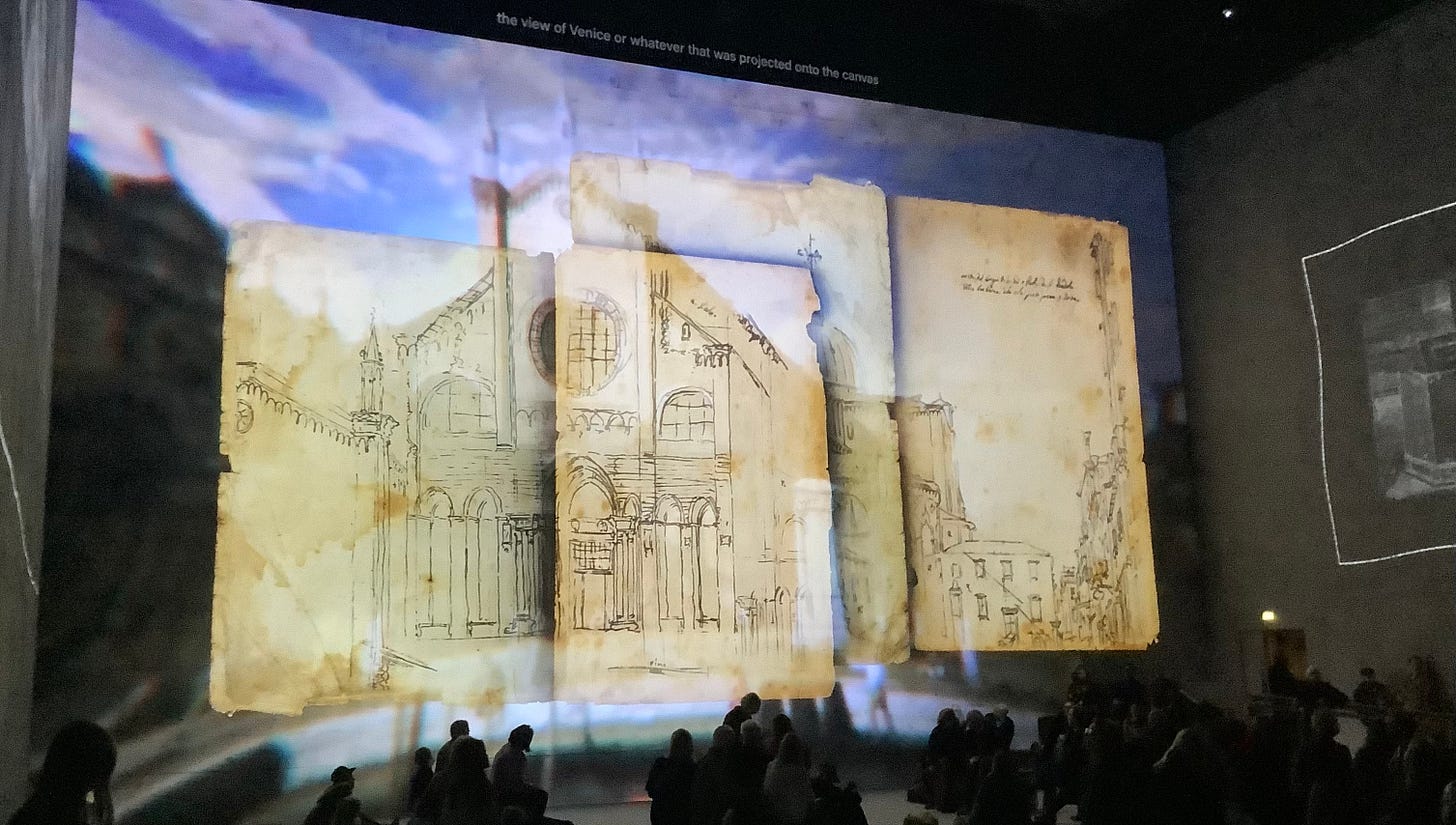

Some of this is a conversation with the history of Western art. Hockney is not a fan of perspective (‘good for architects’) and he reminds us that it was invented by an architect, Brunelleschi. It reduces the artist’s view to a single point, and outside of the picture.

(Perspective is good for architects. Image from ‘Bigger and Closer’. Photo Andrew Curry, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

But, he says, ‘Cameras see geometrically but we see psychologically. If you play with perspective it allows the viewer to wander in and look around.’ Perspective came from a particular moment in Italian history and spread across Europe. Chinese art doesn’t have it.

There’s also a reminder here that the camera was invented long before photography, in the form of the camera obscura, which allowed people to trace images of the world. Canaletto would get his students to do this. Photography was the process of fixing this image chemically, or digitally.

(Tracing the world. Image from ‘Bigger and Closer’. Photo Andrew Curry, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

He’s not really a fan of photographs either, which he says are about a single point in time and space. We might spend three to four seconds looking through a viewfinder; the camera counts in tenths of a second.

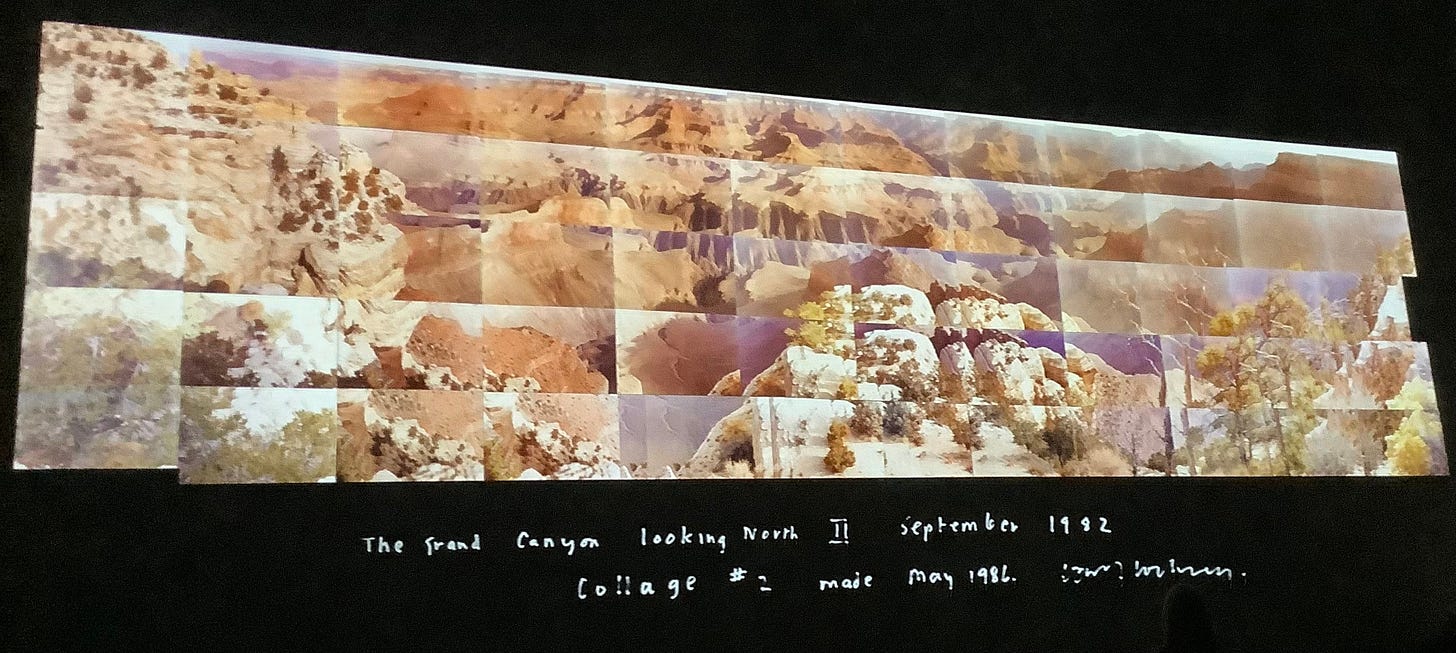

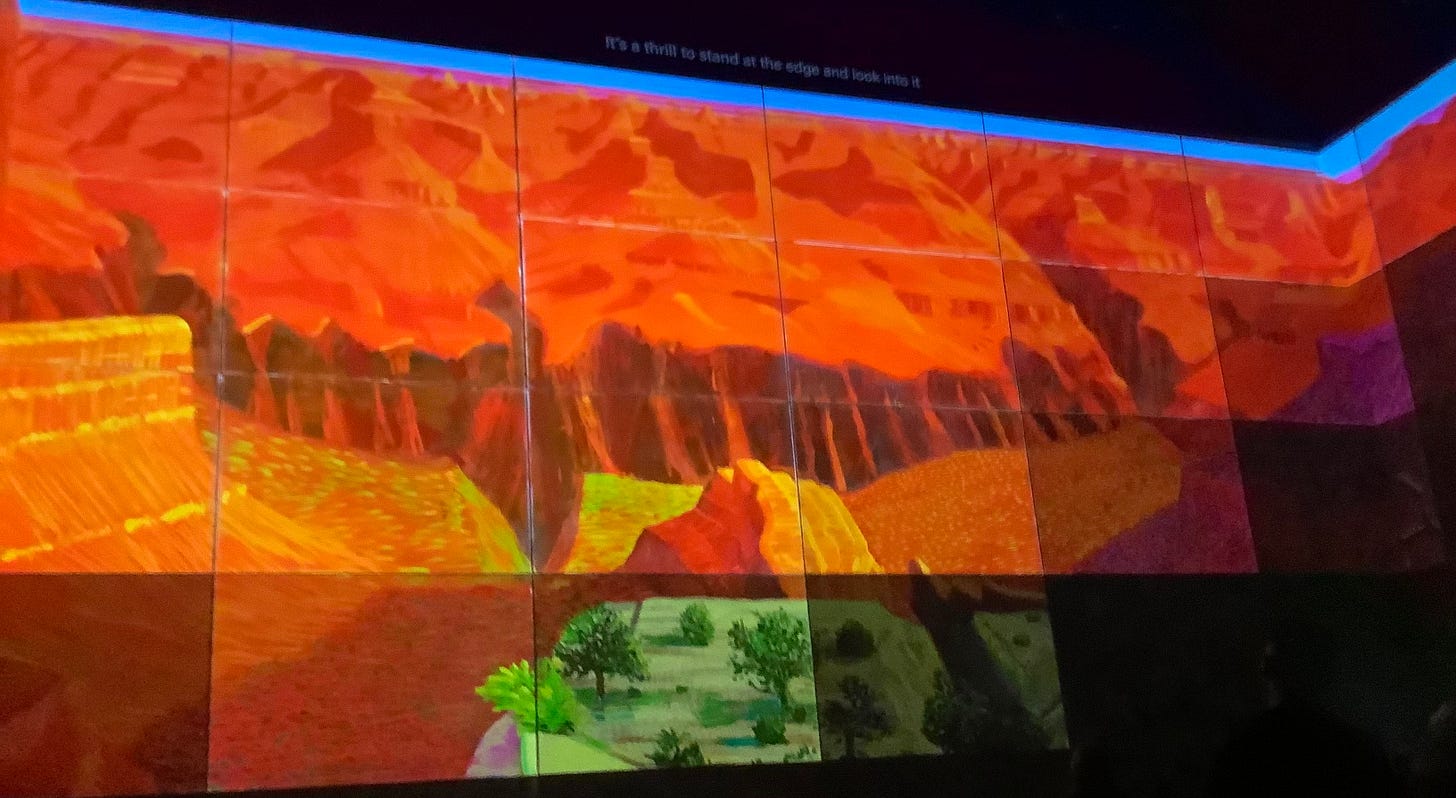

The most interesting element of this, then, were the sequences that showed him trying to undermine perspective, to play with time or space, to get inside the images, often using photos to do it. (The Guardian art critic Jonathan Jones, who hated the show, seemed to have missed this thread in his review).

There’s a sequence of his paintings of the Grand Canyon, which Hockney says has no perspective. In the pictures, you can see what he means.

(David Hockney, photos of the Grand Canyon. Image from ‘Bigger and Closer’. Photo Andrew Curry, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

(David Hockney, The Grand Canyon. Image from ‘Bigger and Closer’. Photo Andrew Curry, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The works comprising multiple photos which together make up a single portrait were also an attempt to step beyond the single moment of photographic time. This is a portrait of a couple doing a cryptic crossword together. Hockney says that using photographs like this puts time back into the work, and also that he doesn’t know, when he starts where the edge will be. (Photography, again, is very clear about its edges).

(David Hockney. Image from ‘Bigger and Closer’. Photo Andrew Curry, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

There’s more here, but I don’t want to spoil the show.

This isn’t a cheap experience. When I did media futures, I used to use a time/cost ratio (pence per minute of experience) to compare different types of cultural experience, and on that scale this comes somewhere close to a Premier League football match.

So there’s also the question of why this kind of experience should be prospering now. I’d say that’s quite an easy question to answer. Photographs are everywhere, and our screens at home are large and high quality.

At the same time, our experience of media, mostly, is casual, episodic, interrupted, and individual. This kind of event requires us to be there, to make an appointment, to be social, to immerse ourselves in it. At the same time there’s also something of the Instagram about it. Lots of people were also taking photos or filming sequences. So it’s maybe also a reflection of the wider shift to an audio-visual culture.

Using McLuhan’s tetrads, we might say that it extends our concentration; it obsolesces the stillness of art; it retrieves the immersive and social experience of earlier cinema; and it reverses into just another passing entertainment.

But: it hasn’t got there yet. I found that the experience of different images on different walls added to my experience. My tip, if you’re visiting, is to take up the offer of staying on after the 50 minutes, and watch it twice—once from each side of the room.

Other writing: music, film

Salut! Live has published the second of my pieces from Celtic Connections, on Transatlantic Sessions, which started out as a television series and is now a short high profile annual tour. An extract:

The format of the show is much as it has been since the television show’s brandname and musicians first migrated to the concert hall almost 20 years ago. Under the musical direction of the American dobro player Jerry Douglas and the Scots fiddler Aly Bain, a group of outstanding Celtic and North American musicians are a kind of house band that mixes songs from a range of guests with material of their own, some traditional, some not.

The guests this year included Martha Wainwright, the American nu-folk singer Amythyst Kiah, the former Hothouse Flowers frontman Liam Ó Maonlaí, Karen Matheson—and, briefly in London, Eric Clapton.

The piece came with a playlist:

And on my Around the Edges culture-ish blog, some notes on Alfred Hitchcock’s fine post war film Notorious. (The motto of the blog ought to be ‘refuse topicality’. )

So the first thing to say is that (Ingrid) Bergman is just breathtakingly beautiful in the film. When she first goes to the home of the Nazi Alex Sebastian, played by Claude Rains, her handlers lend her a sumptuous necklace, which means that light plays all around her face. Bergman’s brilliant white dress contrasts with the black of the Nazis and the grey of Sebastian’s sinister, suspicious, mother.

j2t#429

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.