25 August 2021. Trees | S-curves

Using Tree Equity scores to improve outcomes in poorer neighbourhoods; Was Mozart burned out?

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: Using Tree Equity scores to improve outcomes in poorer neighbourhoods

I hadn’t heard about the concept of tree equity before, but there’s an article in the most recent issue of the ecological magazine Resurgence that explains the idea.

It’s a response to the fact that in American cities there are often fewer trees in poorer areas—which are also, typically, where more people of colour live—and this has adverse effects on health, climate and economic outcomes.

An NGO, American Forests, has been mapping American cities—so far including Houston, Dallas, and Seattle, among others— to calculate the imbalance and to use the data to drive planting of new trees:

The Tree Equity Score incorporates factors like population density, income and employment, race and ethnicity, age, satellite data on tree cover, and surface temperature. The approach was developed in Rhode Island as part of a United States Climate Alliance state learning lab.

The article notes that people in areas with fewer trees tend to be exposed to more heat, more pollution, and suffer from greater stress. Trees create multiple over-lapping benefits, cooling and cleaning the air, which reduces risks of respiratory illness. They also sequester carbon, improve mental health outcome, reduce flooding and water pollution. In short, every neighbourhood should have some.

(Image via Envirobites.org)

Which is why American Forests defines tree equity “as having enough trees in an area so that everyone can experience the health, climate and economic benefits”.

The discrepancies in tree cover are often the result of historic forms of housing discrimination—the practice of ‘redlining’ in the 1930s, under which Federal government labelled predominantly black areas as “risky” investments, which made it harder for buyers to get mortgages and reduced levels of amenity within them. The results now are stark:

This underinvestment resulted in less greenery and more pavement in black neighbourhoods and other communities of colour. A 2020 study found that formerly redlined neighbourhoods are now up to 7°C hotter in summer.

Well, as Jeremy Williams puts it: climate change is racist.

One effect of the American Forests’ programme is that opens up opportunities for careers in tree provision for “overlooked communities”.

It’s data-driven approach is also making rapid strides in making the issue visible and creating action around it.:

American Forests envisions that every lower-income neighbourhood in 100 US cities will have a passing Tree Equity Score by 2030. In May this year, the city of Phoenix became the first in the nation to formally commit to achieving tree equity by 2030.

#2: Was Mozart burned-out?

There’s been a tweet floating around asking which creative artist you would give an extra fifty years of life to, if you could.

You can get lost in the replies, obviously.

At the Marginal Revolution blog, Tyler Cowen decided to take part in this sport. Here’s a flavour of his response:

My answer was Schubert, and here is why:

1. Schubert was just starting to peak, but we already have a significant amount of top-tier Mozart. And I take Mozart to be the number one contender for the designation. Schubert composed nine symphonies, and number seven still wasn’t that great. Some people think number eight was unfinished. Number nine is incredible. Furthermore, I believe the nature of his genius would have aged well with the man.

2. John Keats is a reasonable contender, but perhaps his extant peak output is sufficient to capture the nature of his genius?

3. After the 1982-1984 period, there was decline in the quality of Basquiat’s output. His was the genius of a young man, and drugs would have interfered with his further achievement in any case.

Mozart gets quite a lot of love in the Twitter replies as well. As does Hendrix, also mentioned by Tyler. Shelley, not so much, which surprised me.

Tyler’s discussion of Mozart reminded me of the work of Theodore Modis, who made a good living as a consultant for many years using S-curves to understand rates of change in markets and in other phenomena. Generally, of course, futurists tend to be big fan of S-curves.

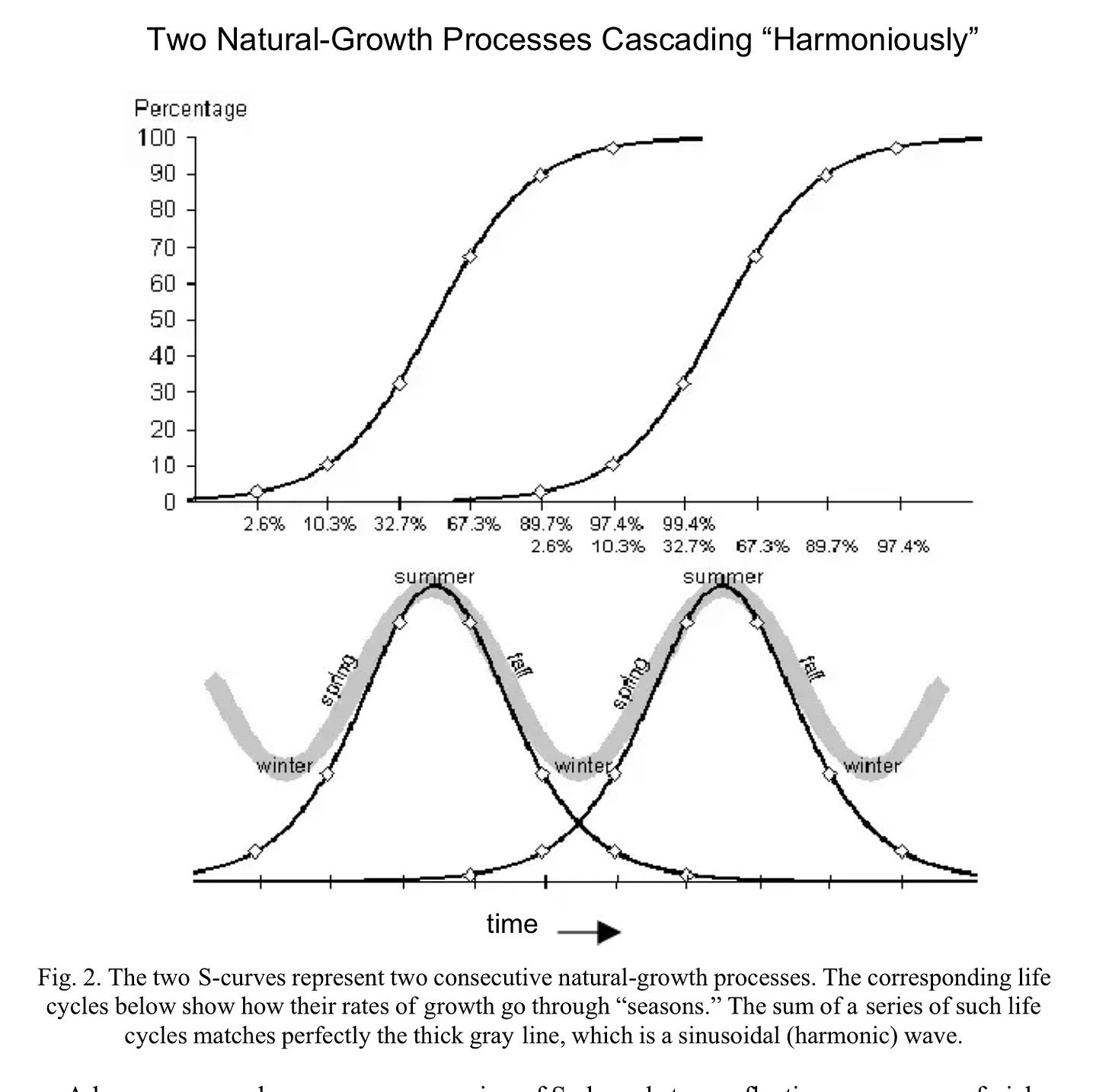

Modis has a nice version of S-curves, which he describes as going from Winter (slow, not much going on), then accelerating through Spring and Summer, then hitting an inflection point and slowing through Autumn and Winter.

(Source: Thodore Modis)

In his book Predictions one of the subjects that he applied S-curves to was the output of Mozart, looking at the K-numbers and mapping them onto Mozart’s life. (I think this was a bit of an S-curve party piece).

He concludes that Mozart was already into the final phase of his productive output when he died. I don’t have the book to hand as I write, but my recollection is that he even uses the S-curve to estimate how many Mozart works we are ‘missing’ as a result of his early death, and decides that it is only a handful.

Of course, there’s also the reverse of this question: which creative artists would have better reputations had they died young? My main candidate for this one is Wordsworth.

j2t#155

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.