25 April 2022. Tech | Russia

The EU will be regulating big tech. // Understanding Russians who support the war involves some nuance.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

1: The EU will be regulating big tech

One of the bits of received wisdom about the tech sector is that the vast American tech giants are too big to control, their monopolies impossible to dent. But without making too much noise about it, the European Union seems to be introducing legislation that will have this effect.

There are two different Acts involved. The Digital Markets Act will regulate competition in the tech space, while the Digital Services Act will cover data use and privacy. It is the first of these, which brings anti-trust measures to bear on the sector, that is likely to have the biggest effect.

Aimed at firms with an individual market capitalization above €65 billion, the act will set out for the first time the rules of how large online platforms must compete in the EU’s market. It could, for example, force Google to give users the choice of alternative email providers when installing a new smartphone or Apple to open its app store to competing services.

As the article notes, this is aimed hard at the integration strategies that all of the tech monopolists employ to maintain their market position. And it gives regulators broader investigatory powers and the ability to levy much larger fines—which is significant, given that in some current cases big tech has been willing to pay the fines levied on them rather than remedy the behaviour complained about.

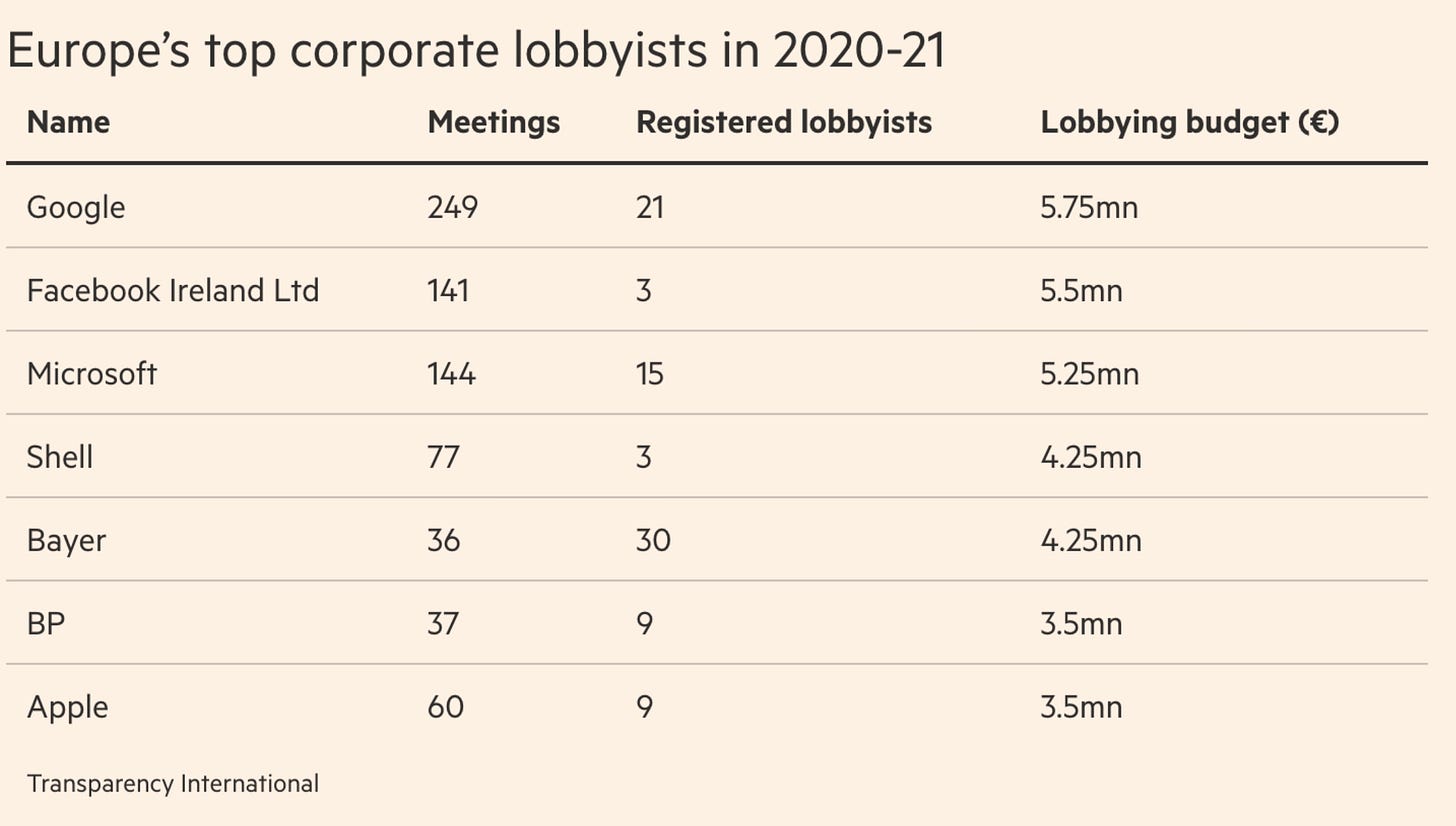

An indication of the concern by big tech has been the way in which they have ramped up their lobbying as the legislation has been taking shape.

According to the independently funded Brussels-based campaign group Corporate Europe Observatory, more than 150 meetings between Big Tech and EU officials have been logged since the start of the current European Commission in late 2019, involving 103 organizations. But interviews with EU officials, lawmakers, and others suggest their efforts have been ham-fisted and largely in vain—and major companies are now shifting their attention to how they might comply with the legislation rather than derail it.

A chart of lobbying spend by businesses in Brussels gives some idea of the scale of this activity.

This has not been a successful strategy. Reading the Ars Technica article—republished from the Financial Times—the most obvious conclusion is that big tech thought that tactics that might well have worked in Washington would also work in Europe:

(Google) planned an aggressive campaign directly aimed at Thierry Breton, the internal markets commissioner who has been instrumental in drawing up the tough new rules against large tech companies. An internal company document laying out the lobbying strategy called for a more intense “pushback” against Breton, who has proposed breaking up companies that constantly ignore EU rules, and “weakening support” for the draft legislation among lawmakers in Brussels. But the move backfired, and Google’s chief executive, Sundar Pichai, ended up apologizing to the French commissioner as he promised that such lobbying was “not the way we operate."

Another lobbying strategy that has been deployed by big tech is to claim that these moves will harm innovation. Nick Clegg, who shills for Facebook/Meta these days, said, “risks fossilizing how products work and preventing the constant iteration and experimentation that drives technological progress." Meanwhile, a consultancy report paid for by Google used the same language, but more so: the DMA, it said, would have a “chilling effect on research and development and innovation."

Given that the thrust of much of the legislation is about increasing interoperability—which I wrote about here a few months ago—this line of attack implies a very particular view of how innovation works.

Anyway, it seems that the tech companies, while still trying to influence the details of the legislation, seem to have realised that the game is up:

Asked to come out publicly to defend the sector, lobbyists are declining the opportunity. “It’s over,” says one, who represents the interest of Big Tech and declined to speak on the record. “I don’t want to be the last one standing, crying. It was a done deal from the start. It’s been an artificial battle. The sector was always going to lose after fighting against the entire establishment.”

Which, given the anti-competitive impact of big tech, sounds like a cue to fetch an extremely small violin. And, when you read the article, the thread that runs through it of special pleading by people who have been paid to represent big tech over the years is quite something.

What’s interesting, of course, is that the need to regulate the tech sector is one of the few subjects on which there is bi-partisan agreement in Washington. US legislators are unlikely to make much progress on all of that this year, but you can’t help but think they’ll be watching to see what works.

2: Understanding Russians who support the war

Social Europe has an article on the responses by Russian citizens to the war. They seem more nuanced than implied much of the coverage in the West, certainly that I have seen. The research, by Public Sociology Laboratory, has been conducted through offline and online interviews since February 27th—currently more than 130 of them. The offline interviews involved talking to people ad demonstrations—both pro-war and anti-war—and during people’s daily routines.

The article is by Svetlana Erpyleva, who is a member of the Laboratory. They are particularly interested in reasons why Russians support the war, and it turns out that there are—completely unsurprisingly—different groups of attitudes:

We often think of those who support the war as people who believe in Russian state propaganda, who believe Ukraine has been ‘captured by Nazis’ and/or that Ukraine (with the help of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization) was planning an attack on Donbas and Crimea, and then on Russia. Another stereotype is that these people support the president, Vladimir Putin, or are ready to ignore the negative consequences of the west’s economic sanctions against Russia. But our research shows that the reasons people support the Russian military operation in Ukraine are more complicated.

They identify five different groups. There’s quite a lot of detail in the article, including extracts from interviews, so this is just a flavour here.

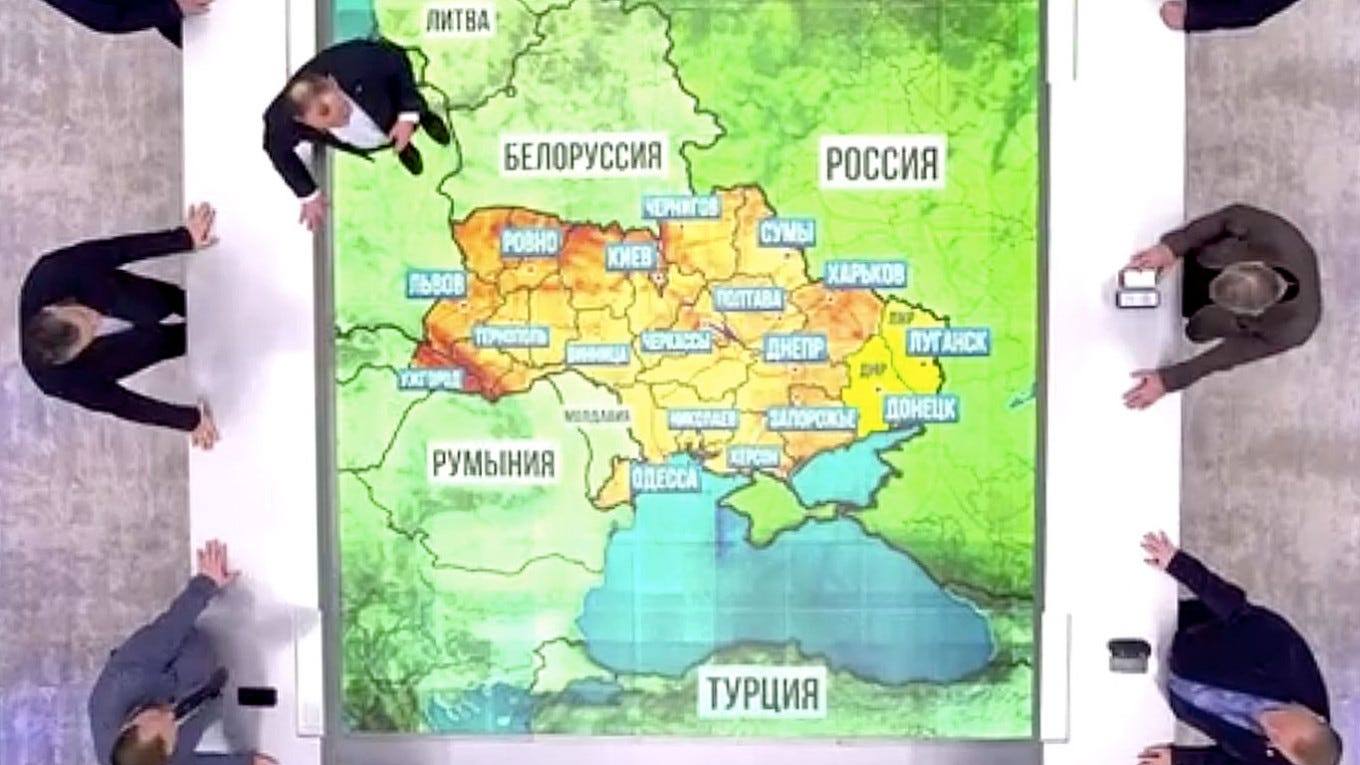

(Russian TV coverage of the war. Image: The Moscow Times. Perviy Kanal / Vremya Pokazhet)

The state propaganda audience:

“These people trust official Russian sources of information (and most often do not consume other media). They justify the war by referring to the need to protect the inhabitants of Donbas from the Ukrainian regime (referred to as ‘nationalist’, ‘Nazi’ or ‘fascist’) and to fight Ukrainian ‘Nazism’ or ‘fascism’ in general... They support Putin and despite the fact that they see internal problems in Russia, they are ready to forgive these problems during a difficult time for the country.

“When conducting interviews with these informants, however, we noticed one interesting pattern: the more time that had passed since Russia’s initial invasion, the more likely it was that these people were ready to doubt their picture of the world.”

Supporters of the ‘Russian world’:

“These are people who formed their attitude to Russian foreign policy (in general, and to neighbouring states in particular) long before the invasion. These are mainly people with imperial sympathies and/or nationalistic views, who dream of a strong Russia which would finally defeat its eternal enemy: the west.

“These people not only justify Russia’s war against Ukraine but welcome it. In their eyes, the conflict between Russia and the western world has been going on for a long time.”

The NATO threat:

“(T)he third group would prefer that there was no war—but, since it has begun, justify the conflict by the need to respond to NATO’s eastward advance. A 27-year-old clerk from Moscow told us: ‘I think that it should have been possible to come to an agreement in the past eight years, find some ways of contact in order to resolve this issue through diplomacy, without military action.

“These people are sceptical of Russian military propaganda and do not trust Russian official media. They use a variety of sources of information, including Russian opposition and Ukrainian media. They tend to believe that the war will lead to economic decline in Russia, the impoverishment of the population and the division of Russian society into warring camps.”

Personal connections:

“(T)he fourth group is most likely small, but still important—people who are personally connected with Donbas. These people consider the ‘new war’ a chance to end the ‘old war’—the ongoing conflict since 2014... The prominent Russian propaganda cliché ‘Where have you been for the last eight years?’, a reference to 2014, is a real-life experience for them.

“These people tend to treat the Russian authorities with indifference or even negativity, but at this ‘critical moment’ they take its side.”

Support ‘despite everything’:

“(O)ne of the most interesting categories of supporters of the war are people who criticise the apparent causes, course and consequences of the conflict yet respond positively when asked directly whether they support the invasion. These people were relatively few among our informants, which is not surprising...

“Our interview with a 49-year-old education worker from Chelyabinsk, was typical: ‘I was born in the USSR, and brought up in the spirit of patriotism, so I support my homeland, my state, because I simply cannot do otherwise.’

“‘I am against the war, of course. I feel very sorry for the people who suffer (in Ukraine), because many of us have relatives, friends and acquaintances there.’”

The researchers think that attitudes towards the war are changing as it continues, but are unlikely to change to outright opposition:

Our hypothesis—and one that we plan to test in the future—is that people’s perceptions of the war are changing significantly as the conflict draws on. We have not observed that people’s initial support for the war was replaced by rejecting it: supporters of the war continue to find justifications for Russian military actions. But in recent interviews we rarely encounter unconditional support for what is happening.

At the same time, it is important to understand the more nuanced reasons why people might support the war—rather than positioning them as “crazy fanatics”:

Russia is in a strange moment. As people who are against the war, we must take people who support it—or who are designated as such—seriously. This does not mean we should share their faith or delusions about the war, but view them as real people, fellow citizens with whom we have to conduct a serious dialogue.

j2t#303

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.