Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to write daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: The spirit of John Audubon in Harlem

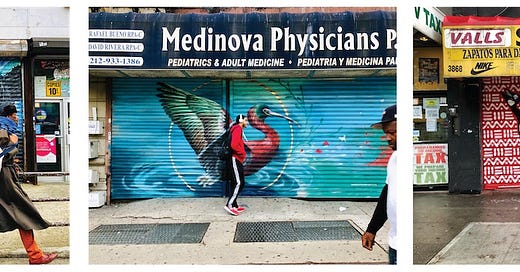

The pioneering American ornithologist lived in Harlem, and the Audubon Society is keeping his work alive with a large programme of bird paintings, representing hundreds of species on the walls and the shopfronts in the area. There’s a wonderful long essay in Orion by Emily Raboteau in Orion magazine reflecting on this project, against the backdrop of lockdown, together with her photographs of some of the murals.

(Photos by Emily Raboteau)

I’m not going to be able to catch the richness or the complexity of the article here, but suffice to say it touches on issues of climate change, urban identity, nature, urban regeneration, race, and quite a lot more. I’ll try to share some snapshots from it.

One of the themes is the sheer pleasure of walking the neighbourhood and enjoying the murals, which take on a life of their own:

Most of the bird murals in Upper Manhattan are spray-painted on the rolled-down gates of mom and pop shops along the gallery of Broadway, at street level. Others are painted up higher on the sides of six-story apartment buildings. Nesting, perching, roosting in the doorways of delis, pharmacies, and barbershops. Lewis’s woodpecker at the Taqueria; the almighty boat-tailed grackle at the Buena Vista Vision Center; Brewer’s blackbird at the La Estrella dry cleaner, and so on—dozens of bird murals, each one marked in a corner with the name of the ongoing series to which they belong: the Audubon Mural Project.

The Audubon Society clearly makes the same links that the writer sees between potential environmental disaster and the pressures on communities such as those in Harlem:

“We know that the fate of birds and people are intertwined,” Audubonmagazine’s editor in chief, Jennifer Bogo wrote me. “That’s especially true in communities, like Northern Manhattan, that suffer disproportionately from environmental and human health burdens”... To my eye, the project is at once a meditation on impermanence, seeing, climate change, environmental justice, habitat loss, and a sly commentary on gentrification, as many of the working-class passersby are being pushed out of the hood in a migratory pattern that signals endangerment.

However, the memory of Audubon is not straightforward. Audubon was, inevitably, a slave-owner. And one of the people whom Emily Rabotaue talks to worries that the birds displace the memory of the people who made modern Harlem—people like “W.E.B. DuBois, Walter White, James Weldon Johnson, Thurgood Marshall, Joe Louis, Paul Robeson, and Count Basie.” Others observe that the mural project runs in parallel with regeneration projects that threaten to displace members of the community:

The murals seemed to [Aisha] like flags planted by an outside entity, laying claim to the neighborhood. Aisha’s uneasy feeling had to do with real estate. Habitat loss. She suspected the birds had landed to invite or delight an incoming class of people with more money than the people who’d lived here for a long time. Hipsters. White folks. The kind of people who stencil birds on their coffee cups, make noise complaints, and drive up rents. The word she was searching for is “artwashing”—a pattern by which developers identify a neighborhood flourishing with art galleries as having potential for major profit.

It’s a long and rewarding article. I’m going to close this with one of the sections from it that in some ways captures the tensions that run through it:

Let us imagine the servant ordered down on all fours

In the manner of an ottoman whereupon the boss volume

Of John James Audubon’s “Birds of America” can be placed.Terrance Hayes offers this image of casual violence in his poem, “Antebellum House Party.” An absurd degradation. The Black body as a prop. The problem with the picture is that it’s so easy for us to imagine. Easier than it is to imagine a sky without birds.

#2: Second hand EVs

There’s a terrific article on Andrew Salzberg’s newsletter on why we need the second hand market in EVs — electric vehicles — to work. In short: without a decent second hand market, you end up not being able to decarbonise the car fleet quickly enough, you create more emissions than you need to in producing cars, and you also pile up a whole lot of equity issues as well.

As he notes, the second-hand car market is much bigger than the new market, since cars have a life of 10-15 years (and EVs potentially for longer, since the engine is so much simpler):

if each new EV can stay on the road longer than their gasoline counterparts, they can help accelerate the retirement of fossil fuel burning cars. That’s one reason to hope that EVs can have long and happy lives in the second hand vehicle market. Since electric vehicles emit carbon dioxide when they’re made, keeping them on the road longer also spreads those emissions out over a larger number of miles.

As he also points out, it makes the EV market more inclusive. A second hand market allows poorer car users to transition from their combustion engine vehicles to EVs at a price they can afford. There’s a technology gain too. Battery technology is improving rapidly, so down the line it would be possible to fit a new battery into a ten-year old vehicle and give it a new lease of life.

What’s not to like? Well, the car companies don’t seem so fond of the idea:

Nissan, for example, seems to make it hard to find new batteries for old cars, and they’re far from the only offender. Tesla is notorious for making it impossible to repair your own car. That makes it both painfully hard and often brutally expensive to repair your vehicle. It’s part of the reason that Norway, the world leader in EV adoption, is seeing many nearly-new EVs sent to the scrap heap.

Without clear law or policy here, as Salzberg says, “we’re likely sending a lot of unnecessary vehicles to the scrap heap, delaying fleet turnover, raising costs, and increasing emissions.”

Salzberg doesn’t say it, but it’s possible that governments may need to impose a “Right to Repair” on the car market—or at least threaten it—to make this all happen. (I wrote about Right to Repair last week). But not allowing users to repair also makes little business sense. Cars which have a longer life have a higher second hand value, and consumers know this: it becomes a calculation in the buying decisions of new car buyers. But businesses often get short-term P&L and long-term market value muddled up.

(My thanks to Charlene Rohr for the link).

j2t#0xx

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.