24 October 2022. Russia | Carbon

‘As if they were lying in coffins’. Lines on the war // Carbon emissions almost at zero this year

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: ‘As if they were lying in coffins’

There’s an extraordinary poem, ‘The Bridegrooms’, by the Russian writer and activist Daria Serenko in the pages of the NY Review of Books. She wrote it in the early stages of the war. It’s translated by Eugene Ostashevsky. I’m sharing this here because it seems to be outside of the NYRB paywall for the moment.

Here’s the first paragraph:

When dead blue bridegrooms from Russia come back from the warthey lie down forever in bed with their brides. They are lyingbetween clean sheets as if they were lying in coffins and the stillliving women are lying next to them as if they were lying in coffinsand all the people in every prefabricated concrete high-rise are lyingas if they were lying in coffins.

(Funeral in Igdir, by Eduard Isabekyan. Via Wikipedia. CC BY-SA 4.0)

When I was younger, this would probably have been described as a ‘prose poem’, but I’m not sure this kind of a distinction really matters much these days.

As the NYRB says:

The corpses receive funerals but the funerals are paired with their weddings, “to avoid going through the expenses twice.” History filters into the poem in unexpected ways—the dead soldier has nothing to wear to his wedding-funeral but his father’s old suit, which is available because “the father got blown up back in Chechnya.” The poem’s conceit is thought through so insistently, as if the fantasy were merely dull fact, that when we reach the last line—which I won’t spoil here—it comes as something of a heart attack.

Serenko was forced to leave Russia in March, and is currently in Georgia. There’s an interview with Serenko in an email from the NYRB—conducted by email through her translator—about the circumstances in which it was written.

I wrote it in a minibus on the way from Tbilisi to Grigoleti, Georgia. I was traveling with other antiwar activists from the Feminist Anti-War Resistance, the group that I helped found in late February in order to protest the Russian invasion of Ukraine. We were taking a short weekend trip together after a very hard week. Before my poem came the sleepless nights that followed the announcement of mobilization in Russia on September 21... On the minibus I was reading a story by the Belarusian writer Tatsiana Zamirovskaya. It was about Walter Benjamin, who tried to escape from Occupied France and committed suicide in a hotel because the authorities of Francoist Spain had pledged to deport him back over the border.

The poem was published initially in Russian on social media on Facebook and Instagram. (The NYRB published it in September.)

There were two kinds of reactions in the comments. Many Russians wrote that the absurd realism of the text gave them goosebumps, and they thanked me. Other Russians found it nauseating and cynical, and they asked, “Daria, it’s dark and horrible in our world anyway; why do you multiply the darkness and the horror, why did you write this thing?” I would answer that it’s not the responsibility of literature to offer people support and pleasure. Literature can do that, but it doesn’t have to.

Serenko is asked about how she sees the future of Russia and of activism. She notes the tensions between those who have stayed in the country and those who have not—“My compatriots who have remained to live under dictatorship become justifiably irritated when those who have left talk about the future.” She’s pessimistic, for the moment, on the prospects for Russia’s activists:

I think that, in the near future, the antiwar activists who remained will face an escalating nightmare—violence, torture, long prison sentences. Also, any kind of legal protections may completely cease to work with respect to antiwar activists. Russia, which has isolated itself from international law, can afford to torture and kill. At the same time, the antiwar movement will continue to grow, and part of it will become radicalized, turning into an underground guerrilla movement. This will be the direct result of actions by the authorities. Antiwar protest will stand on three pillars—women’s resistance, the resistance of non-Russian ethnic groups, and radical guerrilla resistance.

Finally, of course, this being the New York Review of Books, they ask her what she’s reading at the moment:

The last time I read a lot was when I was imprisoned for two weeks right before the war, for posting a red exclamation point on Instagram, since that’s a logo associated with Navalny. Friends and fellow activists had brought me fourteen books, and I was swallowing a book a day in the cell... (Now) I have very little time or strength (because all my strength is spent on activism), and so I have to choose between reading and writing. I choose writing. So what influences me now is not fiction or nonfiction but the war itself, and the fact that I am a citizen of the aggressor country. The current situation is monstrous... I would have preferred that my poem, which you published here, had never existed.

The whole poem is here.

2: Carbon emissions growth almost at zero this year

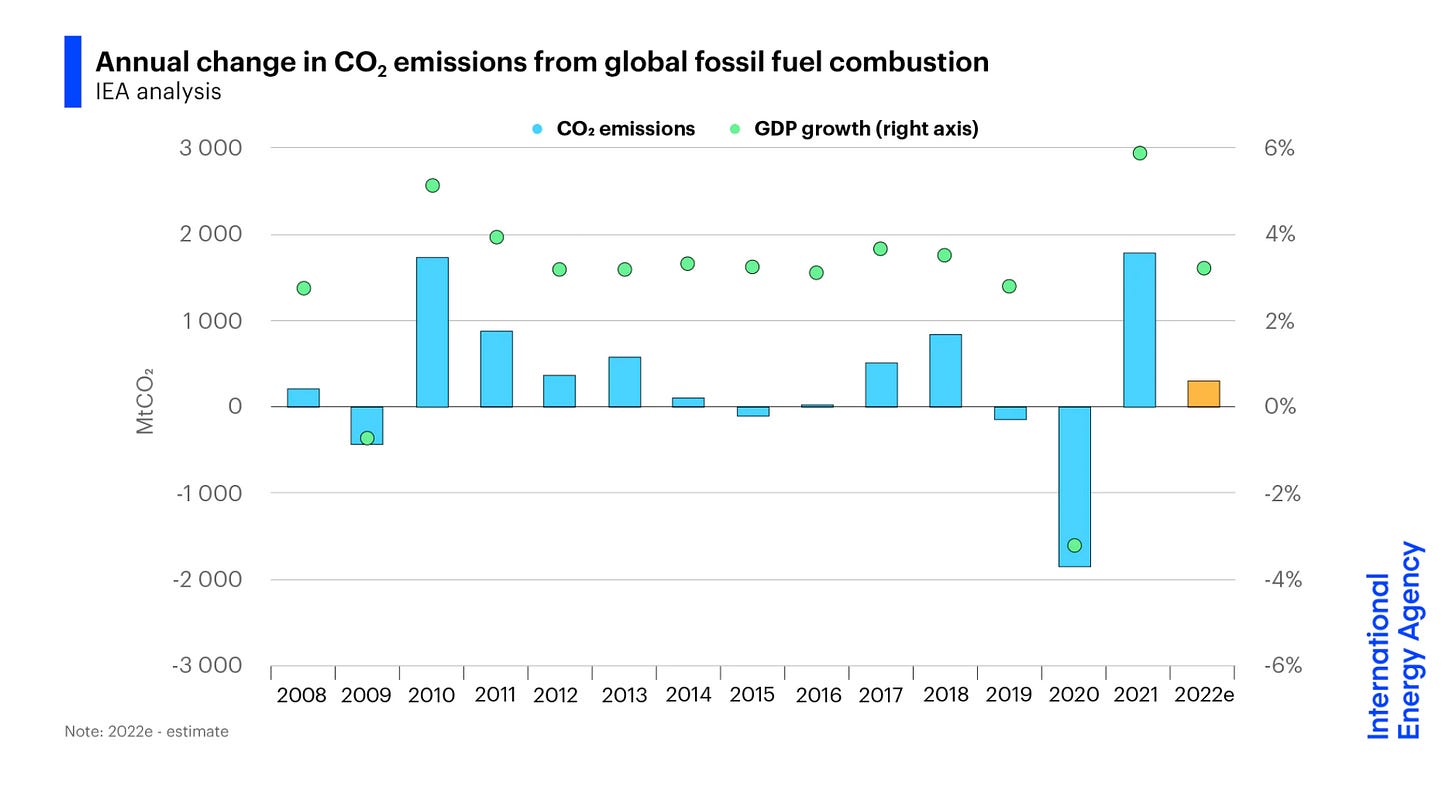

There’s a report by the International Energy Agency which says that there will only be a fractional increase in carbon emissions this year. The reason, it says: the deployment of renewable energy and the increased numbers of EVs. (I’m grateful to Exponential View for noticing this.) The increase in emissions is expected to be just under 1%.

Reading across the chart, 2020 and 2021 really have to be read together—the big fall is because of the pandemic, the big rise came as economies opened up again.

The increase that is here is down to power generation and by the increase in aviation over the course of the year. There’s been a small increase in emissions from coal, which is partly a result of the disruption to the world energy markets caused by the Russia-Ukraine war, although it’s possible that the IEA has over-estimated this.

“The global energy crisis triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has prompted a scramble by many countries to use other energy sources to replace the natural gas supplies that Russia has withheld from the market. The encouraging news is that solar and wind are filling much of the gap, with the uptick in coal appearing to be relatively small and temporary,” said IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol. “This means that CO2 emissions are growing far less quickly this year than some people feared – and that policy actions by governments are driving real structural changes in the energy economy.”

Global renewable energy production has increased by 700 Terawatt-hours, which is the biggest annual increase on record. Two-thirds of this has come from solar power and wind; a growth in global hydropower has also contributed. On the other hand, droughts and water shortages have caused problems for nuclear power production, which has declined.

Quite a big chunk in the fall in emissions has come from declining demand for natural gas, which is a direct result of the Russia-Ukraine war. The direct result of this has been a fall in carbon emissions of around 40 million tonnes.

But that’s dwarfed by the increase in emissions from oil and oil-related use—up by 180 million tonnes. Here’s the data on that:

This has been driven largely by the transport sector as travel restrictions have been lifted and pre-pandemic commuting and travel patterns have resumed. Aviation is expected to contribute around three-quarters of the rise in emissions from oil use, notably due to increases in international air travel. However, the aviation sector’s emissions are still only around 80% of their pre-pandemic levels.

There are two ways to reduce emissions. One is to reduce energy demand through changing usage patterns, and the second is to make existing usage more efficient. The IEA reports a slight increase in efficiency (or in carbon intensity). The IEA data shows a slight increase in intensity—though not as dramatic as we saw in many years through the 2010s. Just for clarity, below the line is good here:

This growth in intensity isn’t going to be enough to hit any meaningful emissions reductions targets any time soon.At Exponential View, they put this into a bit of context. To hit credible emissions reduction targets, this year’s

33.8 billion tons of annual CO2 emission needs to not only stop growing, it needs to be cut to 30.2 billion by 2025 and then 21.1 billion by 2030.

The IEA does note that one of the effects of the Russia-Ukraine war has been to accelerate investment in renewables pretty much everywhere, so it will be worth looking at the effect of this in next year’s data:

(P)romising signs of lasting structural changes to the CO2 intensity of global energy are evident in 2022 – and they are set to be reinforced by major increases in government support for clean energy investment, notably in the US Inflation Reduction Act, as well as in decarbonisation plans such as the European Union’s Fit for 55 package and Japan’s Green Transformation (GX) plan, and in ambitious clean energy targets in China and India.

It’s also the case that a slow global economy will help.

Marshall Kirkpatrick, who writes Exponential View’s climate column each week, also points out that if we’re going to generate change, we do need to mark the moments when things are going in the right direction. He quotes the change-maker adrienne maree brown:

Change comes from cumulative shifts. Reflect to groups how they are accumulating change…or not. Reflect to groups what they are practicing - both in and out of alignment with their values.

j2t#385

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.