24 May 2023. Work | AI

Guess what? The experience of toxic work culture is strongly gendered. // From photography to ‘promptography’.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Guess what? Toxic work culture is strongly gendered.

I think we knew this, but one of the differences between men and women in the workplace is that women are much, much, much more likely to talk about toxic culture. That’s the obvious headline from an article by two researchers who trawled through millions of comments on the employment site Glassdoor, coded them, analysed them, and clustered them. The data are more or less evenly divided between men and women and cover businesses of all types and sizes. (Thanks to Stowe Boyd’s Work Futures for the link).

Here’s their chart, which for clarity shows a subset of their full data set taken between 2020 and 2021.

(Donald Sull and Charles Sull, ‘The Toxic Culture Gap Shows Companies Are Failing Women’. Sloane Review.)

The size of the dots reflects how often it was mentioned; the vertical axis shows the proportion of women who mentioned; the horizontal axis shows the balance between negative and positive mentions of a topic by women, relative to men. Women were 41% more likely than men to mention elements of toxic culture. So although toxic culture is not at the top of the list here (that would be ‘compensation and benefits’) it is both talked about most and the most negative topic.

The article is written by Charles and Donald Sull, and it appears in the Sloan Review. It’s worth pausing for a moment to understand the research that this is based on:

To shed light on these questions, we analyzed the language that 3 million U.S. employees used in Glassdoor reviews to describe their employer between 2016 and 2021... We classified employee comments into nearly 200 fine-grained topics related to corporate culture, leadership, and other features that shape the employee experience. We aggregated multiple topics into two dozen broader themes... We measured how frequently men and women mentioned each topic and theme, as well as how positively or negatively they talked about them.

The research above is actually based on 600,000 or so entries on Glassdoor between 2020 and 2021, partly to understand better the post-pandemic world. (This makes sense since it’s clear from the other talk about the post-pandemic workplace—‘the great resignation’, ‘quiet quitting’, and so on, that the pandemic has been a bit of a faultline in workplace relations).

The authors define toxic culture as

a workplace culture that is disrespectful, noninclusive, unethical, cutthroat, or abusive.

And they point out that although huge costs on the people who experience it—more women than men, it would seem from the way the research is presented—it also imposes big costs on organisations:

In an earlier study, we found that a toxic culture was 10 times more powerful than compensation in predicting attrition during the first six months of the so-called Great Resignation. Even if they don’t quit, employees in toxic environments are more likely to disengage from their work, exert less effort, and bad-mouth their employer to others.

Exposure to a toxic culture also “increases the odds that employees will suffer from anxiety, depression, burnout, and serious physical health issues.”

The researchers do the usual stuff of controlling for types of industries, and so on, but given how big the gap is here, this is just researcher prudence. For the record, though:

Chefs exhibit the largest gender gap in toxic culture in our data, and women chefs were nearly twice as likely to discuss toxic culture in their reviews... Nor are knowledge workers or professionals immune to the toxic culture gap, with attorneys, management consultants, product managers, and electrical engineers all reporting higher-than-average toxic culture gaps.

There’s a helpful chart in the article of the 155 occupations in their research that show the biggest gender gap when it comes to toxicity. Here’s the top (i.e. the worst) 10%. There seems to be little relationship between proportion of women writing reviews—which looks to have a relationship with how gendered the occupation is—and the gender gap on toxicity.

(Donald Sull and Charles Sull, ‘The Toxic Culture Gap Shows Companies Are Failing Women’. Sloane Review.)

The article also has the best-performing 10% of occupations, and it’s worth noting that there only three, of 155, where men are more likely to mention toxic culture than women. These are: child care and development; adjunct medical specialist; and design engineer.

So it is not surprising to discover that overall, gender is the second biggest predictive factor in whether an entry will mention elements of toxic culture; the biggest one is whether the review is written by an ex-employee or not, which underlines the point above about toxic culture being a strong predictor of employee departures.

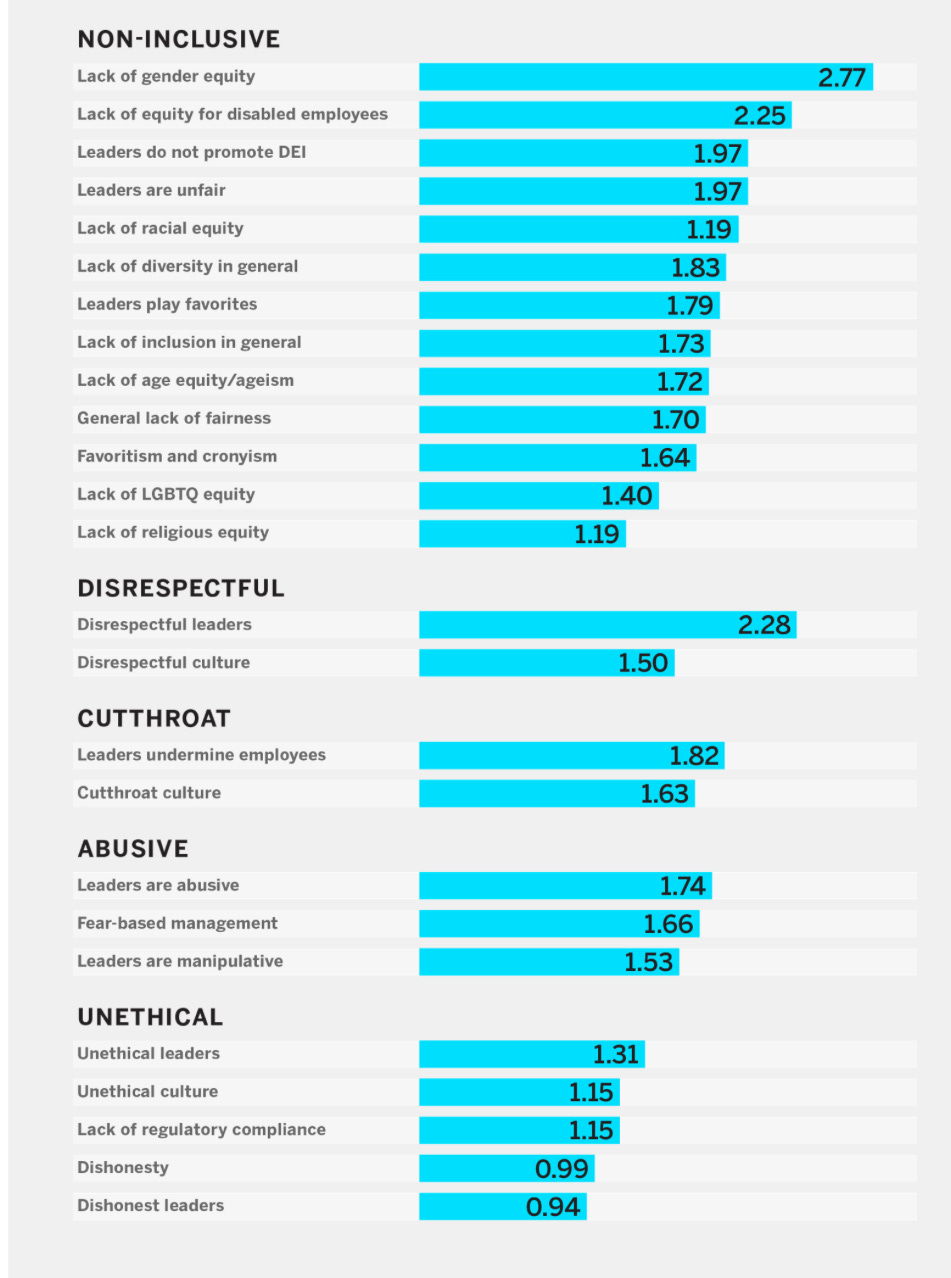

The Sulls have a chart in which they break out the different factors that they rolled into their ‘toxic culture’ cluster, and it’s a long list:

(Donald Sull and Charles Sull, ‘The Toxic Culture Gap Shows Companies Are Failing Women’. Sloane Review.)

The scores are the ratio of the number of times a subject was mentioned by women against the number of times it was mentioned by men. The one that jumped out at me here was the gender gap on ‘disrespectful leaders’. The scores below it, on aspects of leadership behaviour, underline this. (The bar for ‘lack of racial equality’ seems to be misdrawn, given the printed score).

Again, in this long list, there are only two areas that men are more likely to mention than women, and fractionally, and they are both about dishonesty.

The authors note that there are things here that can be fixed quite quickly, if leaders want to. For example, there are sometimes pockets of toxic culture within otherwise satisfactory business cultures.

But they seem to me to have missed the biggest point about their chart at the top of this piece. The vertical line shows the point at which men and women have the same opinion about something. To the right, women’s opinons are more positive than men’s; to the left, women’s opinions are more negative.

Three of their 21 clusters are (slightly) to the right of the line, and two are on the line. The other 16 are to the left, some a long way to the left: women have more negative opinions of them than men do. In other words, the data suggests to me, the world of work is still set up, heavily, to favour men and not women. And looking at the breakdown of the factors within toxic culture, most of them arise from this rather larger problem. Doing something about toxic culture is a necessary step, sure, but it is still dealing with symptoms and not causes.

2: From photography to ‘promptography’

I’ve been meaning for some time to write about the AI-photo controversy involving the photographer Boris Eldagsen and the Sony World Photography Awards. The short version: Eldagsen is a photographer whose current work involves the (very sophisticated) use of AI to develop images that look like photos, but aren’t.

He submitted one of these to the Sony World Photography Awards, and won a prize. He declined the prize, noisily, because he said it wasn’t a photograph. Lots of the details of the ensuing spat are online, partly because almost all of this content is curated by him on his own website, in multiple languages.

I’m not that interested in the argument between him and the awards organisers CREO, although they maybe weren’t paying as much attention as they should have been. I’m more interested in the argument about whether this is photography or not.

But first, I’m going to use the relevant image, which is Eldagsen’s copyright, because it’s hard to have this discussion without seeing it.

(© Boris Eldagsen, “The Electrician” from the series "PSEUDOMNESIA", 2022-ongoing, courtesy Photo Edition Berlin)

The image was created using DALL-E 2, an image generator developed by OpenAI. The Art Newspaper has this account:

In his submission, Eldagsen described the image as “a haunting black-and-white portrait of two women from different generations, reminiscent of the visual language of 1940s family portraits”.

After the prize was announced, he interrupted a presentation at the awards to make it clear that he wasn’t accepting it—he says he did this because he’d only realised when in the room that despite having won an award he wouldn’t be invited to speak from the stage. In declining the award, Eldagsen says he wants to ‘drive debate’ about the use of artificial intelligence to create images. He amplified his onstage remarks with a statement on his website:

“I applied as a cheeky monkey, to find out if the competitions are prepared for AI images to enter,” Eldagsen wrote. “They are not.”

“How many of you knew or suspected that it was AI generated? Something about this doesn’t feel right, does it?” he added. “AI images and photography should not compete with each other in an award like this. They are different entities. AI is not photography. Therefore I will not accept the award.”

Eldagsen says we need a new word—and a new category—to make sure that we don’t get confused between images generated by photographers and images generated by software. Neologisms are always interesting to me because they are a marker of change, even when they don’t stick. Eldagsen’s preferred word is ‘promptography’:

“Promptography is done with prompts. Photography is done with light,” Eldagsen told the BBC. “I think it’s very important to differentiate these (two things) by terms, and then to have an open discussion about this in the photography world. Is the umbrella of photography large enough to say this (type of imagery) is part of it? Because the visual language is the same.”

I’m willing to take this at face value: there’s a long interview with him in Urbanautica about the importance of being able to trust that images are authentic. It also incluses an intriguing selection of his AI-generated images.

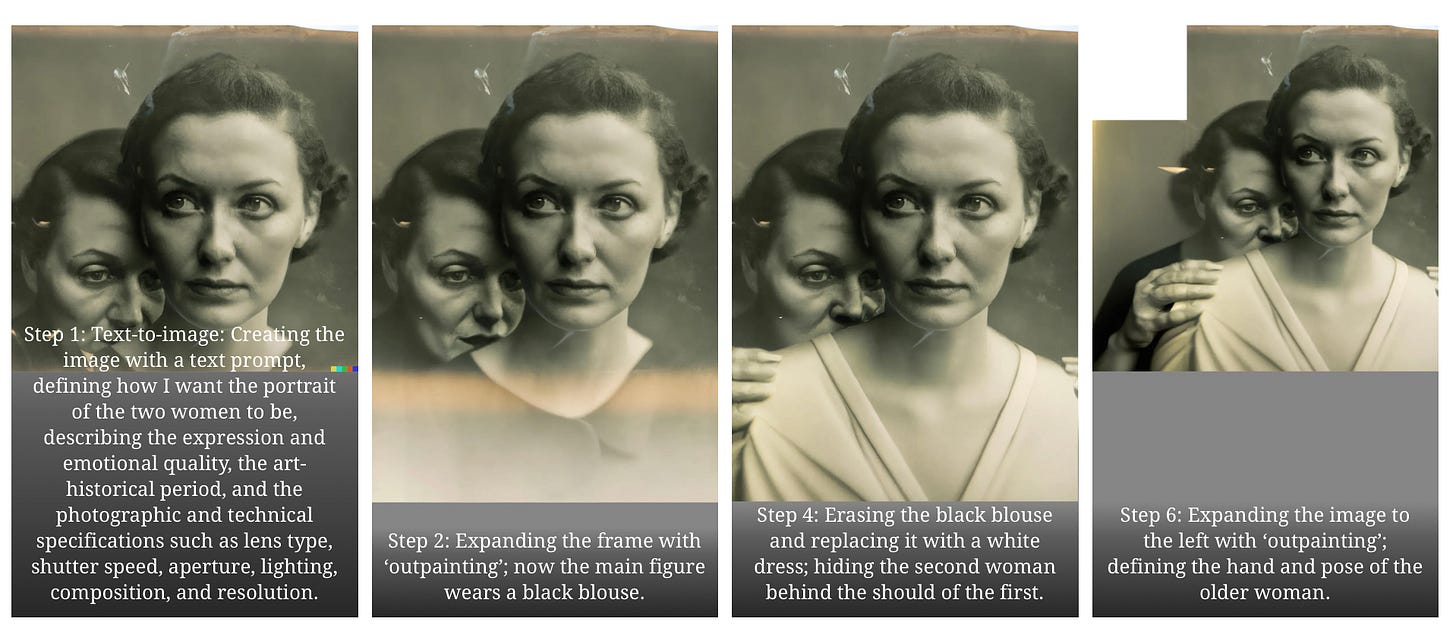

All the same, there’s something about his position that is nagging away at me. The thing is, what he’s doing is not simple. In one of the pieces published since the controversy (he was certainly right about declining the award ‘driving debate’), he describes what he did to make ‘The Electrician’. It’s not simple work. It involves 20 stages, of which eight were reproduced in the Australian photography magazine Talking Pictures.

(All images © Boris Eldagsen)

And, of course, you can also see—AI or not—that this is a composed image, even while passing itself off as an early-ish 20th century collotype.

Although Eldagsen makes a strong assertion about the difference between photography and AI (light versus prompts) photography is already well past that stage. Any digital image is doing as much with technology adjustments and filters as it is with light, and a lot of contemporary work is then treated digitally as well.

And some of this argument also reminded me of the recurring controversy about hyper-realist painting, which is impossible without photography.

(Magda Torres Gurza, ‘La Hora Del Te’. CC BY-SA 4.0)

So it seems that this issue is maybe not so pressing when it comes to a ‘photograph’ such as ‘The Electrician’. As a piece of art, it’s not making any more claims on authenticity than any other portrait of two unknown women might do.

In fact, it might be quite liberating, as Eldagsen said to Talking Pictures:

What impact do you see AI imagery having on photography as an art practice?

One hundred and seventy years ago, Baudelaire pronounced the nascent medium of photography to be the “mortal enemy of painting, (…) refuge of all failed painters, the untalented and the lazy”. Today, AI artists are berated in much the same way by photographers. Back then, photographers took the likeness, the realistic representation, away from painters. It proved a liberating blow, the prerequisite for the development of modern painting.

But the issue of distinguishing between fake and real images in day-to-day news is a real issue. The Bellingcat founder and creative director Eliot Higgins made this point, satirically and graphically, in a widely shared tweet in March.

(Source: Eliot Higgins, Twitter)

And that ship might already have sailed.

j2t#459

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.