Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

1: A week in Kyiv

The writer and novelist James Meek has just spent a week in Kyiv, flying out of the city in the last 24 hours, and filing a series of pieces for the LRB blog, pretty much one a day. They’re all worth reading, since he’s a fine writer, and the pieces entwine present with past. Here’s some extracts.

(Kyiv at sunset. Photo by Trev Ratcliff/flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

16.02.22

The first is a distinction between Kyiv Alpha and Kyiv Beta. The first is the modern European city, with its boulevards and coffee shops. The second is the city in the shadow of prospective war.

Kyiv Alpha is Euro-Kyiv, three hours from Stansted on Ryanair, a Kyiv for mini-breaks, poor Western artists and ravers, a Kyiv for bankers and IT startups, the Kyiv of hipster bustle, grand silver age facades being restored with extravagant slowness, fastidiously presented filter coffee, contactless payment and wifi; also of poverty in the banlieues.

Kyiv Beta, on the other hand, doesn’t exist, well not exactly, and not yet:

Kyiv Beta, the other possible Kyiv of 16 February, of traffic jams of refugees heading west out of the city with mattresses tied to the roofs of their Toyotas, of columns of smoke rising from government buildings, of flames gouting from the windows of banks and department stores... a city without power, heating, water, mobile signal or internet... Kyiv Beta is a fear, a prediction, a hallucination – a panicky American delusion, some would say – that hasn’t come to be, and may never do so.

Nonetheless, even in Kyiv Alpha, the endless war with Russia has its place. Statues, of course:

Just outside the headquarters of what could be called either ‘the Ukrainian secret police’ or ‘the Ukrainian version of the FBI’, a new sculpture has appeared commemorating the soldiers who died fighting separatists and their Russian allies in the east of the country. A Ukrainian cossack on a rearing horse rams a spear down the gullet of a creature that has the two heads and crowns of the Russian imperial eagle, but the body and jaws of a dragon.

17.02.22

In which James Meek tries to track down a copy of Mikhail Bulgakov’s book The White Guard in Kyiv.

[Bulgakov] based the book on his experiences of multiple armies – German, Ukrainian nationalist, Bolshevik, Polish – attacking Kyiv at the end of the First World War... The layer of myth Bulgakov places over the map of Kyiv, its strange mixture of the adoring and the bitter, and its mood of good people oppressed by mortal danger, was one of the main reasons I became interested in Kyiv in the 1990s. The book isn’t so easy to find here now, although the mood it evokes is present again.

During this search he ends up talking to a bookshop manager, Anastasia, who is 23. At first he thought that, unlike most Ukrainians, Anastasia could not speak Russian. This isn’t the case:

Gradually it became apparent that, in fact, she did speak Russian, but had made a conscious decision not to. Born and raised in Odessa to parents who spoke, as she put it, ‘surzhik’ – a mixture of Ukrainian and Russian – she went to a Ukrainian-language school, but did also speak Russian. Five years ago, exasperated by Russia’s military intervention in eastern Ukraine and by Russian propaganda, she decided she was going to try to expunge Russian from her mind. She wouldn’t speak it. If somebody spoke to her in Russian, she would answer only in Ukrainian.

He doesn’t find a copy of The White Guard, but he does get to visit the Bulgakov museum, in the house where the writer was born. There’s a young Ukrainian woman on the tour with him:

She’d read The Master And Margarita three times, and found new things in it each time, but had never read The White Guard. I asked her what she thought about Anastasia’s radical decision. ‘I respect it,’ she said. ‘I just haven’t quite got to that point myself yet.’

—

22.02.22

The 22nd isn’t any old date.

Two months ago Vladimir Zhironovsky, the politician who once seemed the most dangerous face of Russian nationalism but is now just another ageing Putin fanboy, predicted the world would ‘feel our new policy’ at four a.m. on 22 February. It was on 22 June that Hitler began Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union. In a hit Russian folk song of the time, written a few days later, the date was liltingly linked to Ukraine:

It was June twenty secondRight on the stroke of fourBombs fell on Kiev, radio news saidThat we were having a war.

The conflict in the Donbas is eight years old now, almost nine. Meek goes to visit a film-maker who has made a film about what it’s like to live in the Donbas now:

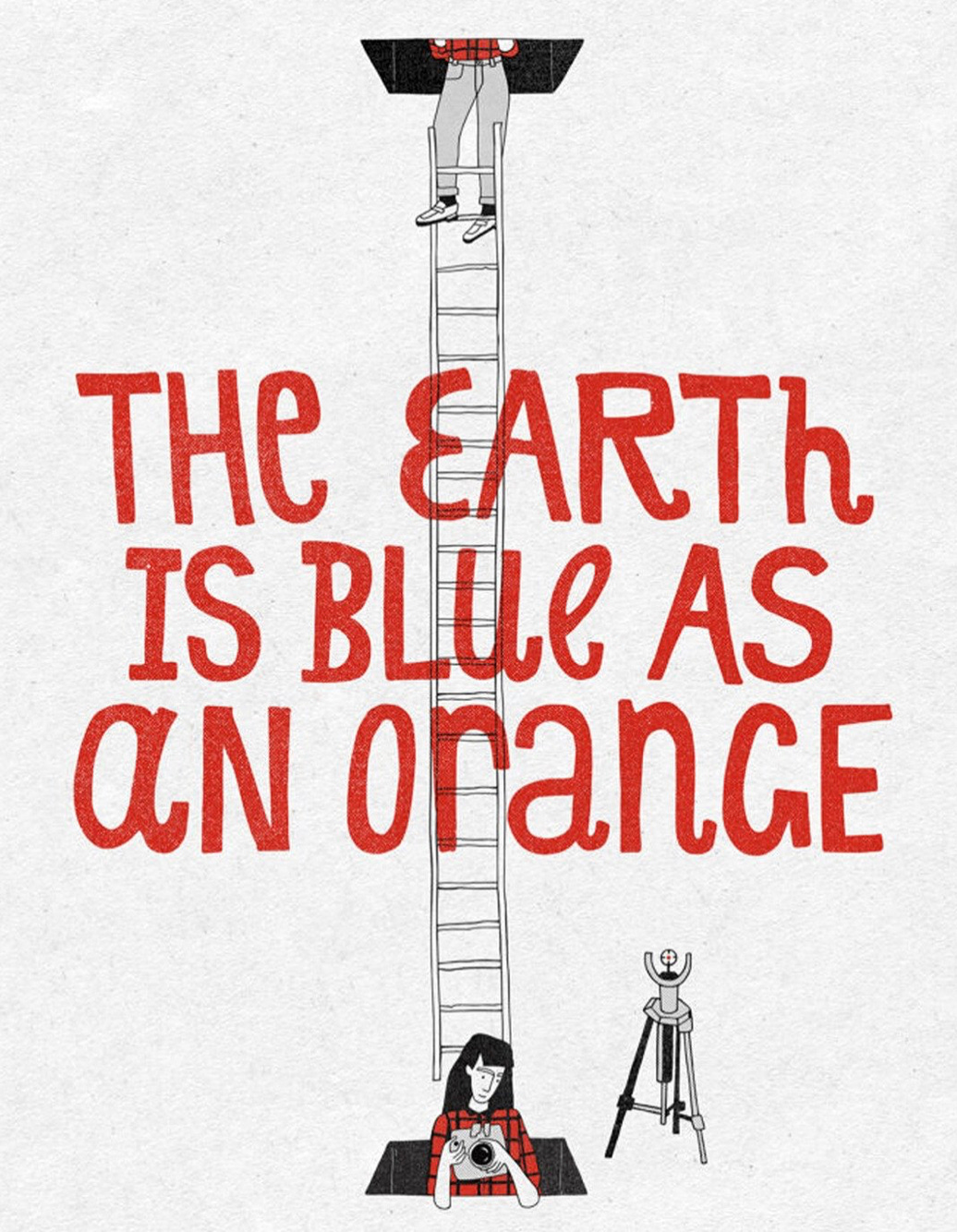

Iryna Tsilyk’s extraordinary documentary The Earth is Blue as an Orange is about a family of five – four children and their mother – living in the ‘grey zone’ of the Donbas conflict, in a town called Krasnohorivka, a couple of miles from territory controlled by the rebels and, now, openly, by their Russian sponsors. In the course of the film, while they deal with shellfire and fear and the breakdown of basic services, the children’s school somehow keeps going and the family makes a short feature of their own.

The film is about to go on tour, to the Baltic states, and the family is going with it—a break from the grim conditions in the grey zone:

The water supply has been cut off to the town of six thousand people, and won’t be restored for months. She has to go two kilometres to get water from a well. The town used to have gas, but when that was cut off, everyone made their own stoves and burned coal; then electricity came back, and people abandoned their stoves for electric heaters. Now the electricity keeps going off. Sometimes people die of cold. Mobile signals keep cutting out. Movement around town is constrained by minefields and snipers. And yet in spite of everything the house is their home. She wants to be able to go back to it; she hopes it will still be there.

2: Telling stories of national humiliation

One of the themes in some of the coverage of Putin and Russia has been about his view that the collapse of the Soviet Union having been a Russian humiliation. Some have drawn parallels with how China’s loss of power and status in its ‘century of humiliation’—starting with the Opium Wars, ending with the Japanese occupation—shaped the worldviews of the Communist Party leaders who made the 1948 Revolution.

Putin was a middle-ranking KGB officer when the Soviet Union collapsed. I’d heard the idea before that his worldview was shaped by this idea of collapse, and that his political purpose was to regain respect for Russia. But I’d not realised until I read a 2018 piece in History how visceral that moment had been for him. (Perhaps I hadn’t been paying attention). The writer was Shaun Walker, a former Moscow correspondent who published The Long Hangover, a book about Putin’s Russia, in that year:

As a 37-year-old KGB lieutenant colonel stationed in the East German city of Dresden, Putin watched nervously as angry crowds stormed the city’s huge Stasi compound in December 1989. Overrunning the offices of the East German secret police, the crowds moved on to its inner sanctum: the KGB headquarters. Putin called for armed backup to protect the employees and the sensitive files hidden inside, but was told no help would come. “Moscow is silent,” said the voice on the line. He had no choice but to go outside and lie to the crowds that he had heavily armed men waiting inside who would shoot anyone who tried to enter. The bluff worked.

—

(Image of Putin via Max Pixel, CC0)

But the idea that in that moment in Dresden he was watching the power of the Russian state wither away—as indeed he was—stayed with him as he gained political power. Walker also notes an article he wrote in 1999, just before he became President:

“For the first time in the past 200–300 years, Russia faces the real danger that it could be relegated to the second, or even the third tier of global powers,” Putin warned. He called on Russians to unite to make sure that the country remained what he called a “first-tier” nation.

Russia isn’t the only country to behave erratically in the face of notions of national decline, of course. The pervasive idea promoted by Brexiters that Britain has been ‘humiliated’ has been mocked (rightly) by commentators such as the Irish writer Fintan O’Toole. As he wrote in Heroic Failure,

This desire to experience the vicarious thrills of humiliation is possible only in a country that did not know what national humiliation is really like.

And, as critics of Brexit might say, be careful of what you wish for. I’m not saying this to get into an argument about Brexit, more to underline how important status is to people who think they have lost it. Because, after all, status is a fundamental element of human behaviour, to the point where perceptions of it, and of its loss, trump other considerations (pun accidental). O’Toole again:

Humiliation is not an objective reality. It is calibrated against one’s sense of one’s own status. If you’re used to travelling business class, you may feel humiliated by having to sit in economy; but if you’ve always sat in economy, it’s just normal.

Russia is still the sixth-largest economy in the world, by purchasing power parity, but objectively its status has declined since the days of the Soviet Union. The destruction of the economy by marketisation and privatisation in the 1990s made all of that worse. There are plenty of ‘humiliation’ stories it can tell itself.

There’s another whole literature (and here) on how China’s ‘century of humiliation’ has shaped its policy, and I haven’t the time to go into that here. In general, China has been more subtle about how it has deployed that historical story in shaping political, economic, and diplomatic narratives, even if some small voices in China think it is time to move on from it. As with Russia, and as with Britain, these are not benign stories. They elevate nationalism, and they focus on particular versions of history to do it.

——————————-

j2t#268

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.