24 August 2021. Food | Economics

What the Free Fridge movement tells us about food; wrestling with the coming decade of economic change

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: What the Free Fridge movement tells us about food

Well, what’s not to like about the Albany, New York, urban Free Food Fridge Albany project?

There are now six urban fridges across the city, funded by donations, and stock fresh food, and if you need some, you help yourself. No charges, no questions.

This is how the project is described in a piece in Yes! magazine:

Fridge beneficiaries can retrieve anything from milk to veggies and prepared meals. It’s impossible to count just how many people have benefited—the system is anonymous by design—but Anderson says it’s been “extraordinary” to see the impact: residents enjoying fresh okra for the first time in decades because it’s been mostly unavailable in Albany; neighbors forming relationships with local farmers; even some folks who relied on the fridges earlier in the year now have the resources to donate to it.

(Image: Free Fridge Food Albany)

Jammella Anderson founded the project when she became aware of the way in which the pandemic had increased food insecurity. She asked her Instagram followers what she should do about it, and one of them suggested that urban fridges could be a way to help. The Albany project is part of a growing international movement, Freedge.

The movement asks important questions about how to improve access to healthy food:

If we truly want everyone to have enough food, Anderson says, we need to look at the bigger picture, which includes making sure people have enough money to buy the food they need, making sure the abundance of food we already have is distributed effectively, and making sure young people are learning how to grow and cook their own food.

There’s more in the article, which is worth reading, but the reason it perhaps caught my attention was that when I was working on our Future Food Environments project for Impact on Urban Health last year, a couple of things became starkly (and surprisingly) clear to me.

The first was that the current food system is broken. It exports billions of pounds-worth of external costs to the rest of the society, in poor environment, ecological, and public and person health outcomes.

The second was that one of the ways to address that was through a demand that healthy, affordable, and accessible food was a right, not a market exchange.

Our community research (done by Shift Design) also found that people in households with lower incomes were very aware of the ways in which the food system discriminated against them in terms of cost and accessibility of healthy food.

You can read that report here. Of course, you can read the Free Food Fridge project as another version of communities having to club together to feed their hungry, as the food bank network does.

But sometimes radical demands need a physical expression to bring them into sight—a material pocket of the future in the present, if you like. And certainly Anderson has a radical demand in her head. She wants to challenge the

prevailing attitude that poor, Black, Indigenous, and people of color, as well as others who disproportionately face food insecurity, deserve only leftovers, day-old bread, or scraps. The Free Food Fridge flips that idea on its head...

“This is all fresh food from the earth that people who are going food-insecure should be able to have.”

#2: Wrestling with the coming decade of economic change

I had a look at the launch report for The Economy 2030 Inquiry, which is one of those things that the British government ought to be doing, but won’t. It’s being run by the Centre for Economic Performance and the Resolution Foundation, and is funded by the Nuffield Foundation. There is a heavyweight looking list of Commissioners from across the political spectrum, including ex-CBI Director General Carolyn Fairbairn, LSE Director Minouche Shafik, TUC General Secretary Frances O’Grady, and Nicholas Stern.

It characterises UK economic policy over the next decade as being influenced by some big factors that are all inter-acting with each other—COVID-19, Brexit, Net Zero, demography and technology:

These major changes to the UK have usually been considered in isolation, but they will be taking place in concert. Their interactions – which are poorly understood – and not just their contemporaneous nature, will shape the pressures and opportunities facing the UK. Policy makers need an integrated approach to managing these shocks if they are to navigate a successful path through the 2020s.

One of they questions they ask is whether the UK is ready for this scale of change. Contra much of the received wisdom about change, they suggest that the first two decades of the 21st century have seen “a period of flat, or even declining, dynamism”:

This can be seen between sectors, where the reallocation of workers between growing and shrinking industries in the 2010s was at its lowest since the 1930s. If the reallocation rate had remained flat in the past decade, rather than falling, then an extra 2 million jobs would have moved sectors... At the level of individual workers, the rate of voluntary job-to-job moves was 37 per cent lower in 2019 than in 2001.

And of course, this lack of dynamism has coincided with a period of poor productivity growth in the UK economy.

The launch report runs to 70+ pages, and there’s quite a lot of high level detail coverage here, most written in non-technical English. (I’m imagining that they’ll write a lot more after a two-year Inquiry.)

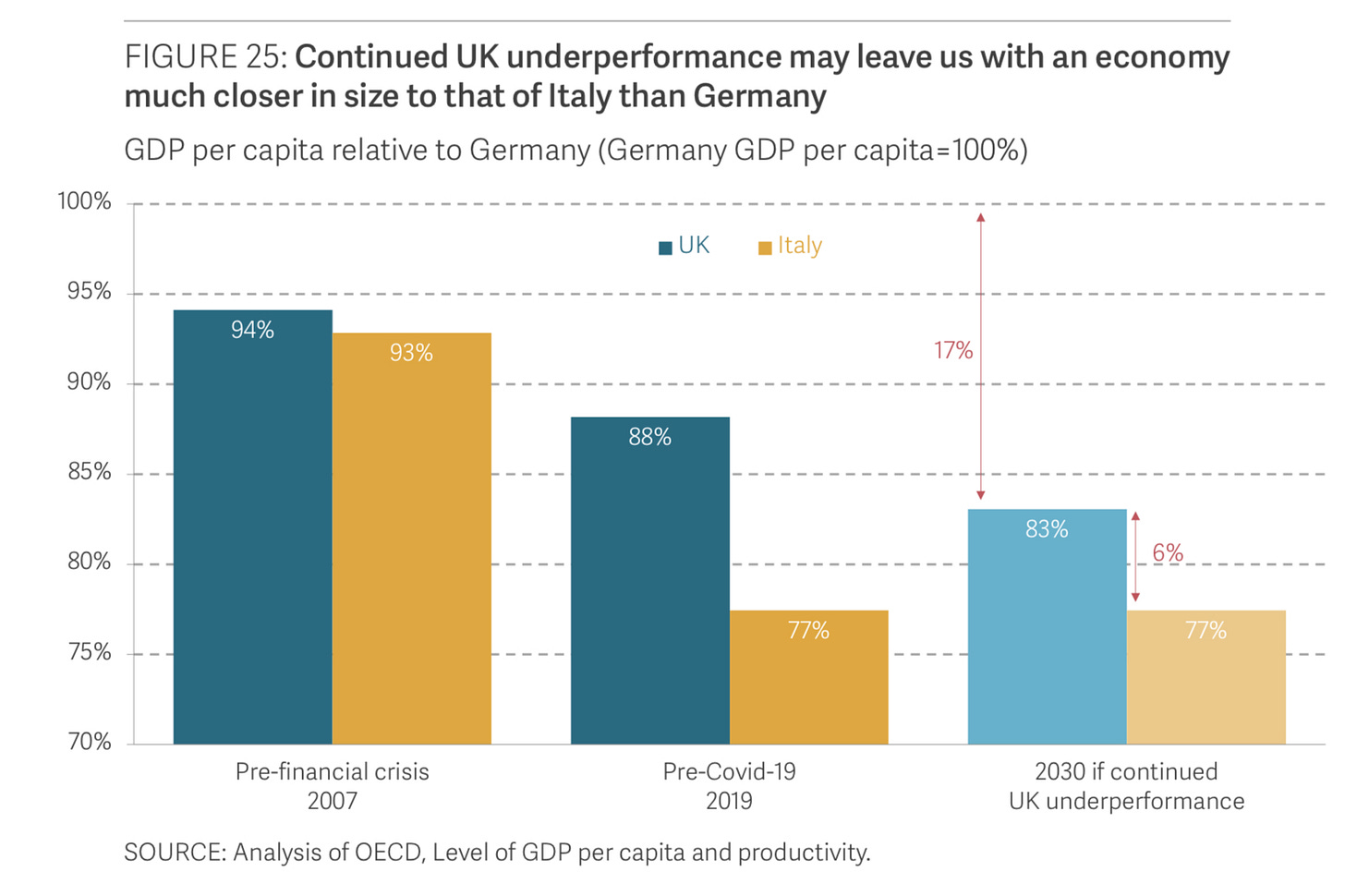

There are sections in here looking ahead at likely change over the next decade; whether the UK is ready for these changes; the economic legacy that is the backdrop for policy (this isn’t completely gloomy); and a view on why the next decade is critical. There are some telling charts as well.

(Chart: The Economy 2030 Inquiry)

Because the UK’s last significant period of structural change was in the 1980s—and frankly the jury is still out on the impact of that—the report does draw out four lessons we can take from that period where there might be some measure of agreement:

First, the state can play a potent role in shaping, not just responding to, the nature of structural economic change. Second, major reallocations of capital and labour can be an important part of the dynamic process of generating significant increases in living standards for many, at the same time as they create painful social and economic dislocation for others. Third, managing the costs of major economic reallocations is incredibly hard to get right and requires a coherent governing strategy if trade-offs are to be resolved reasonably and costs and benefits shared equitably. Any notion that periods of intense economic change will largely take care of themselves can be dismissed. Finally, the consequences of mis-managing economic change are not just painful in the short-term – they can endure for a generation or more.

One of the missing discussions in British politics is about the way in which low investment and low productivity is reducing incomes relative to other countries—perhaps because it happens so slowly.

Without getting into the argument about economic growth here, productivity increases improve the range of choices a society has—people can choose to take productivity gains by working less, for example; higher productivity societies can afford more social spending, and so on. I’m hoping that the 2030 Commission will open up this discussion.

Update on hydrogen: I wrote about the price forecasts in the UK government’s Hydrogen Strategy yesterday. There seem to be other holes in it as well, given that 2050 Net Zero is a legal requirement in the UK. Analysis by Friends of the Earth for the Guardian suggests that the ‘blue’ hydrogen that is a central part of the strategy—made with fossil fuels but with attached carbon capture and storage technologies—will still release considerable carbon emissions.

j2t#154

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.