24 April 2023. Time | Coal

Taking time, making time // Divestment works. It does reduce emissions.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Taking time, making time

I stumbled across a review of Jenny Odell’s recent book Saving Time and was immediately intrigued. Maybe not so much by the account of the book itself—reviewers seem to find it frustrating, although some more frustrating than others—but by what it means that books like this are being published at the moment.

Odell is a multi-media artist and writer whose last book, How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy , published in 2019, was a surprise best-seller.

In the Los Angeles Review of Books, Mary Retta, who is at the more sympathetic end of the reviewers of Saving Time , discusses the argument. At its heart, this is a simple idea: that the notions of time that we live by now are a product of capitalism and colonialism.

(The station clock at the Musee d’Orsay, Paris. Photo: Andrew Curry, CC NC-BY-SA 4.0)

This is not exactly a new idea: E.P. Thompson certainly covered off the capitalism part in a famous essay, ‘Time, Work-Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism’, in 1967, even if parts of his argument were lated contested.

But then again, as Andre Gide famously said:

“Everything that needs to be said has already been said. But since no one was listening, everything must be said again.”

And so to the LARB review, which hints that our experience of lockdown may be one reason why we are listening better now:

In the first few months of the pandemic, people’s perception of time shifted … While 2020 may have brought skepticism of linear time to the mainstream, symbols like the ouroboros prove that various cultures have rejected the notion of standard time for centuries. Similarly to the ancient Egyptians, Native Americans have long viewed time as cyclical, drawing on processes from nature like the growth of mycelia out of decay and the flow of one season into the next as proof of the nebulous lines between day and night, or even life and death.

Odell argues that the modern clock was “made with the express purpose of colonizing and subduing marginalized people”, although I suspect that the factory workers of the Industrial Revolution, closer to home, might think this story a little narrow. But the sense of it is probably right:

Odell chronicles how the clock has mutated and multiplied, ensuring that every aspect of our days is carefully cataloged and controlled. There is the “personal clock” governing how we spend our days; the “climate clock,” noting how much time we have left on a dying planet; and, of course, the “corporate clock,” which accounts for time as money, and which all workers are forced to live on for the majority of their lives.

As Retta notes in her review, little of this is provocative these days. But Odell also deepens some of this with a section that analyses how and why our time is taken from us:

This is a refreshing balm to the mantra, touted in magazine articlesand TED Talks , that individuals must “reclaim” their time, with no instruction manual on how to do so. How are Black people meant to reclaim their time, for example, when the police can easily and legally steal their time through long periods of incarceration? How can a mother reclaim her time when social constraints have made it so that she alone must give her time to her children’s moods, health needs, and school schedule before spending it on herself?

(The ouboros, by an anonymous medieval illuminator, via Wikipedia. Public Domain.)

Part of this argument is a story about the limitations of linear time. Retta notes that the Egyptian ouroboros, a symbol which is several thousand years old, which has no beginning and no end, is more visible in digital culture, and may represent the stirrings of a different idea of time:

I am fond of the title Saving Time, because it implies a mutualistic relationship between temporality and the individual or communities that experience it. To save time could be to collect it, but it could also be to rescue it—from misuse, from rigid definitions, from people or entities who make time feel imposing rather than friendly, alive, and personal.

The book isn’t a manual on how to save your own time—it’s more about ideas and frameworks. For example:

One such tool is a helpful graph that illustrates the periods throughout the year that sundial time runs ahead of or behind the standard clock. “The graph shows both readings of time,” Odell explains, “yet they are not equal,” as the sundial allows for a stretchiness of time—some minutes longer than others, some unaccounted for all together—in a way that the clock does not.

But we are all locked into patterns of thought that have dominated our societies, certainly in the richer world, for 200-300 years. Escaping from this is a bigger challenge. Retta quotes a passage from Toni Morrison’s novel Jazz to illustrate this:

“This notion of rest, it’s attractive to her, but I don’t think she would like it,” she writes... They fill their mind and hands with soap and repair and dicey confrontations because what is waiting for them, in a suddenly idle moment, is the seep of rage.”

We have says Retta, “become unaccustomed” to what enters our lives if we think of time differently. All the same, linear time is a feature of modernity, and connects to ideas of progress and so on.

A review by Constance Grady in Vox made this thought explicit by pairing Saving Time with Pooja Lakshmin’s book Real Self-Care, and suggested that taken together they might help us think about a world beyond capitalism.

Because Real Self-Care also tells a story about time:

By making time for ourselves, Lakshmin argues, we are able to find the space to enact systemic change on the world.

She has come to this argument through experience of a residency as a psychiatrist, which she found so difficult that she dropped out for a couple of years:

Many of her patients were struggling with systemic problems, not psychiatric problems. They needed child care and health insurance, but all Lakshmin was able to offer them was antidepressants and therapy. As Lakshmin would later write, “This isn’t just about burnout, it’s about betrayal” — betrayal of individual people by a state that failed to provide them what they needed to live their lives.

At the end of her review, Grady connects the two books in this way:

This advice, too, is in alignment with Saving Time: a reminder that we don’t exist as individuals awash in a sea of indignities against which we are powerless, but as human beings with human relationships in which all kinds of possibilities exist: connection and help and responsibility and solidarity.

One of the things I argue in my (forthcoming) chapter on the future of cities and the future of work is that our cities are now longer able to reproduce themselves, and two of the reasons for that are about a shortage of time and a failure of care. These only work now for the wealthy.

Can we fix this inside capitalism? That’s a huge topic. But we can’t fix it inside the form of capitalism that we currently have, with both the levels of extraction it requires, and the vast external costs that it dumps on everyone else.

2: Divestment works. It does reduce emissions

It turns out that when banks divest from coal companies it has the effect of reducing carbon emissions. I mean, you’d think it ought to, but it’s also the case that some investment businesses continue to insist, possibly not with the best of motives, that engagement with carbon-emitting firms is a better strategy for change than divestment. So since it was Earth Day at the weekend: let’s state this baldly: divestment works.

(Frimmersdorf Power Station in Grevenbroich, Germany. Photo by Bodoklecksel, via Wikipedia. CC BY-SA 3.0.)

Harvard Business School research has now gathered the evidence together—the Working Knowledge note says that although the divestment movement started in 2006, this is the first time that there has been evidence of impact. (That seems like a strong claim, but I don’t have time to check it).

Just a reminder of the issue:

Coal... is the source of more than a fifth of all CO2 emissions and is more carbon-intensive than any other energy source; phasing out coal-fired power production is therefore critical to reaching net zero. The coal industry is also reliant on large amount of capital, typically from banks.

Boris Vallée and Daniel Green started collecting evidence of the impact of divestment in 2021, and published a working paper (pdf) last summer. Their conclusions are summarised in an HBS ‘Working Knowledge’ note:

Coal firms that face strong divestment policies from their historic lenders reduce their borrowing by a quarter compared to their unaffected peers. This capital rationing leads to reductions in CO2 emissions, as divested firms are more likely to close facilities.

The reason for this is that it’s now hard for coal companies to find alternative sources of finance:

The number of banks that facilitate coal-related deals is so small—and the relationships so deeply entrenched—that by default, these bankers have disproportionate influence over what gets financed. Coal-fired power plants owned by companies that are exposed to bank divestment policies are more likely to be retired, the research shows.

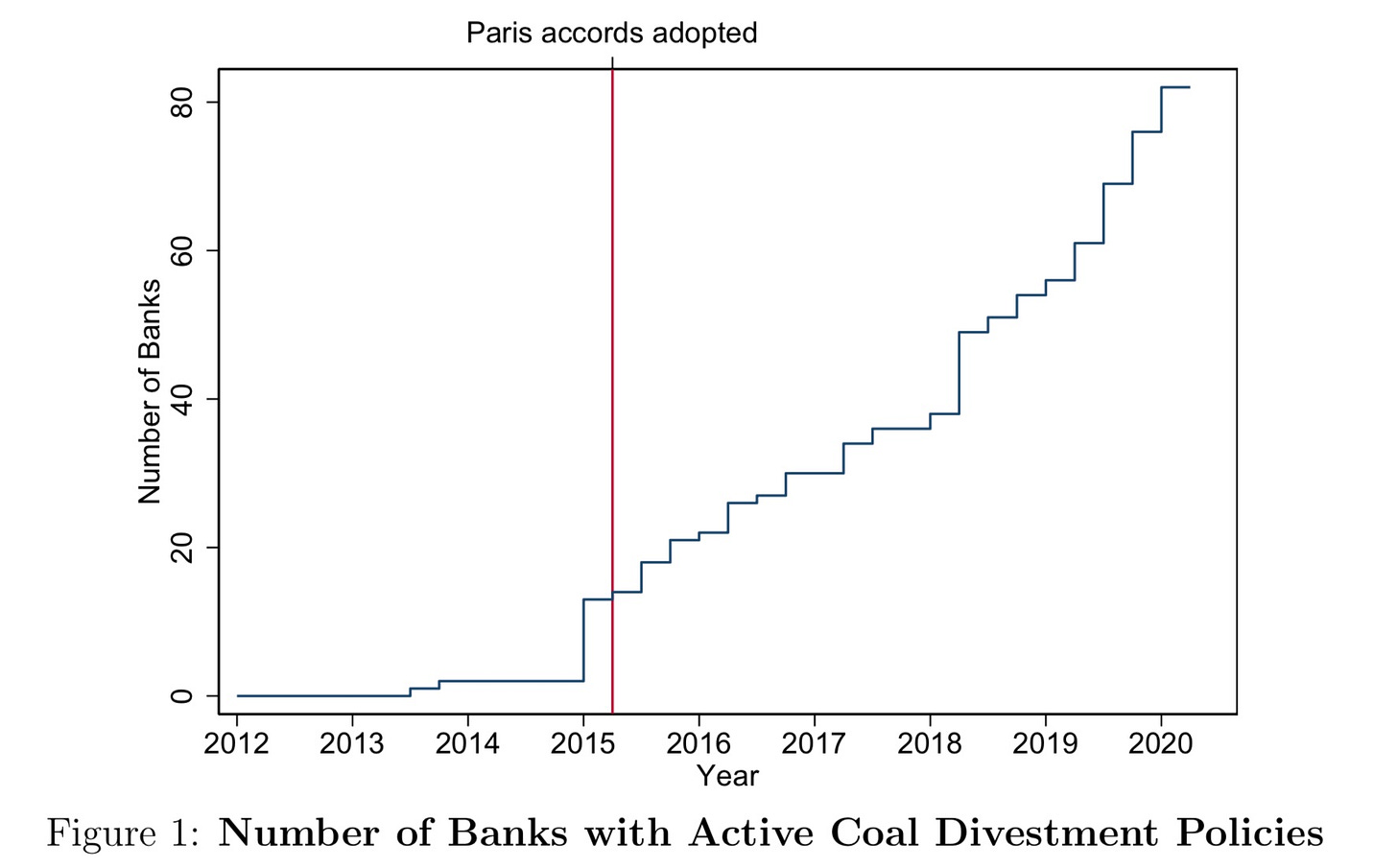

It’s probably worth summarising the research quickly. They examined 12 years of data between 2009 and 2021 on banks’ coal divestment policies (using data from the non-profit group Reclaim Finance); they examined coal company financial statements, and coal plant operating data, as well as speaking to bankers that have divested from coal since the 2015 Paris Accords, as well as reviewing data from the Global Coal Exit List, maintained by the Berlin non-profit Urgewald.

Charts and tables from their analysis is included at the back of the working paper.

(Source: Green and Vallee, ‘Can Finance Save the World? Measurement and Effects of Coal Divestment Policies by Banks’)

It also turns out that (who could have guessed this?) that most coal financing comes from banks with weak divestment policies.

The full paper is written in the driest of language, but it’s worth sharing part of their summary of Table 7, where they summarise their findings:

Table 7 shows that coal-fired power plants owned by firms more exposed to coal finance bans are more likely to face early retirement than plants owned by less exposed firms.... In fact, all of the effect is coming from the period starting in 2015, when coal divestment policies start. All else equal, a plant with a one standard deviation higher exposure to coal lending bans is 48% more likely to be retired in a given year. Column 4 shows that the magnitude of the effect does not differ for plants owned by large and small firms. Column 5 shows that plants owned by borrowers with a low share of coal activity are more likely to close because of coal lending bans... more diversified firms are better able to substitute into different investment opportunities.

The researchers seemed slightly surprised by the strength of these effects, at least when interviewed for the Working Knowledge note. The money quote from the article, from Boris Vallee, is this:

“What we found in this case is that banks divesting from coal directly leads to real impact—more than anyone thought.”

The data also suggests to me the importance of strong public policy positions on emissions. Banks only started to take divestment seriously once it was clear that the Paris Accords were going to be signed. This also raises the obvious question: if it works for coal, would it work for other fossil fuel investments?

Other writing: neuroscience

My son has been writing a series of long but accessible posts talking about aspects of neuroscience at his King Cnut newsletter. Posts so far have covered language, beauty, and, most recently, memory. Here’s an extract:

[F]rom the 1960s to the 1980s, scientists discovered that various parts of the brain were inextricably linked with various types of memory. For instance, rabbits who learned a blink response to a specific stimulus could still do that response with a massive lesion to their hippocampus. Where was the response localised? To the cerebellum. The striatum was found to be responsible for habit learning…

When humans are given a tough learning task, you often see activity in the medial temporal lobes (MTL), as if we are trying to memorise that task. But as we get better at the task, the activity transfers from the MTL to the striatum. Activity in both is negatively correlated, suggesting that they represent two different approaches to the same task.

j2t#449

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.