23 September 2022. Godard | Payments

The man who broke cinema. // Do Visa and MasterCard have a future?

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open. Have a good weekend!

1: The man who broke cinema

I’d been trying to piece about the impact of the film director Jean-Luc Godard, following his assisted death in Switzerland at the age of 91, that wasn’t just a recital of his better films or a complaint about his politics.

A piece by Jared Marcel Pollen at the Verso blog (spotted by those omnivores at The Browser) places Godard’s work in the context of the rapid cultural shifts of the 1960s—he doesn’t say this but it’s possible to imagine that Godard is to cinema what the Beatles and Dylan were to popular music. And he also opens up an idea that appears in several of the reflections after Godard’s death, the Godard effectively brought ‘modernism’ into cinema, exploring ways to portray time and space that had been pioneered in the writings of Joyce and others.

On the first of these thoughts, Pollen pulls no punches:

Between 1959 and 1967, Jean-Luc Godard made 15 feature films, a magnificent run that included the masterpieces À bout de souffle, Vivre sa Vie, Bande à part, Pierrot le Fou, Masculin Féminin and Week-end. This era, from when Godard first started making films to the beginning of his revolutionary period, constitutes perhaps the greatest series of films made by a single filmmaker. These years saw an accelerated transformation in cinema, when the way in which films were made, and what films could be expected to accomplish, changed radically.

On the second, he connects Godard’s work to that of Joyce (whom Godard referenced in interviews) and also Thomas Pynchon:

If we can compare Godard’s work during this period to anything, it would be the novels of Thomas Pynchon and James Joyce. Unsurprisingly, Godard often cited the latter as a key influence. In Pierrot le Fou, the character Ferdinand (played by Jean-Paul Belmondo), a failed writer and a stand-in for Godard himself, breaks the fourth wall, reading aloud from Godard’s own notebook as he explains to the audience his concept for a new kind of novel...: “What lies in between people: space, sound, and color. I’d like to accomplish that. Joyce gave it a try, but it should be possible to do better.”

Pollen expands on the connection between Joyce’s work and that of Godard, suggesting that Joyce had seen the novel as “a dumping ground for all culture”, and that in the 1960s Godard extended this idea to film,

throwing in literature, music, painting, comic books, advertising, criticism, journalism, news headlines, radio broadcasts and dance numbers. “One can put everything in a film,” he once said. “One must put everything in a film.”

Of course, timing is everything. Godard was able to do this in the 1960s where earlier radical film-makers were not because the ‘60s was marked by the breakdown of the barriers between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture. Godard took advantage of this by scavenging wherever he could: he’d read the last few pages of a book in the store, and borrow the idea, or even just take something from the synopsis on a dust-jacket. When he made a version of King Lear, he didn’t bother to read the play.

(Godard at Berkeley, 1968. Via Gary Stevens/flickr. CC BY 2.0)

And that sense that everything is in the film spilled over into his visual style as well:

You never have time to fully absorb anything in a Godard film... Voices come in and out, images flash across the screen, music starts and stops, characters read from books and then put them down, a line of action will begin before being cut off abruptly. Nothing is nailed down, everything is in flux, and there is never any sense, as Frederic Jameson once wrote, that any of these materials “will be put back together by the spectator in the form of a message, let alone the right message.”

That sense of visual saturation reminded me that one genre that picked up this visual style—but emptied out all cultural meaning—was the music video, where similarly directors were free to construct a bricolage of visual references without needing to worry about how the spectator might ‘read’ it.

One can only sustain this level of creative and cultural energy for so long, and Godard maybe recognises this in his 1967 film Week-end, in which civilisation reverts to cannibalism. The final title read: ‘fin de cinema”. And in ‘68, Godard did abandon cinema, at least for a while:

But by that point, he had already shown that cinema, like literature, could be a restlessly experimental form that could act as a delivery system for philosophical ideas and radical politics, and do so in a way that was accessible and entertaining. Few artists, if they’re lucky, ever achieve this, and even fewer survive.

There are other pieces that perhaps go beyond the formalities of an obituary. A piece in n+1 by the film editor Blair McClendon at least caught a sense of the transformative power of great art:

Loving Godard did not mean thinking he was a particularly good person—only that when I needed desperately to believe that the world was more vast than the little circle of my own anguish, he showed it to me. I modeled myself on him, sometimes consciously, sometimes less so. He read Faulkner, so I read Faulkner (it didn’t stick). He read Marx, so I read Marx (it stuck). He had a penchant for aphorisms, whose very conviction was convincing enough. He was, above all, committed, and that is what I understood an artist had to be.

But McClendon’s piece isn’t just about his fanboy discovery of the work. He explores some of the contradictions as well:

He was vehemently anti-consumerist, but his pop-art sensibilities and earnest love for a variety of commodities meant that he tended to portray objects with a greater sense of aura than any advertiser could ever hope for. Cars appear in his work like the very incarnation of sex appeal, whether they’re speeding runaway lovers through the night or shuttling back and forth from a floundering film set in full ’80s boxiness. Godard was so good at seduction that you might get to the end of Contempt and arrive at the conclusion that you, too, wanted to die, covered in red and bound up with an Alfa Romeo.

For a more conventional overview, Alison Smith’s piece in The Conversation is measured and informative. I also enjoyed Douglas Morrey’s article in Politico, with its description of the French New Wave as being ‘Punk before “punk”, in a piece that tracks Godard’s deliberately antagonistic relationship with both cinema and television.

And before I finish here: I also liked this short visual essay about Godard’ visual aesthetic:

2: Do Visa and MasterCard have a future?

At his Finanser blog Chris Skinner has a guest post about the future of Visa and MasterCard. They’re not things that we give much thought to, but they underpin a big part of the architecture of payments systems worldwide. Between them, the two companies account for three-quarters of world card payments.

The short guest post, by Panagiotis Kriaris, Head Of Business Development for Unzer, a German payments firm, nonetheless asks a simple question: might their days be numbered, at least in the long-term?

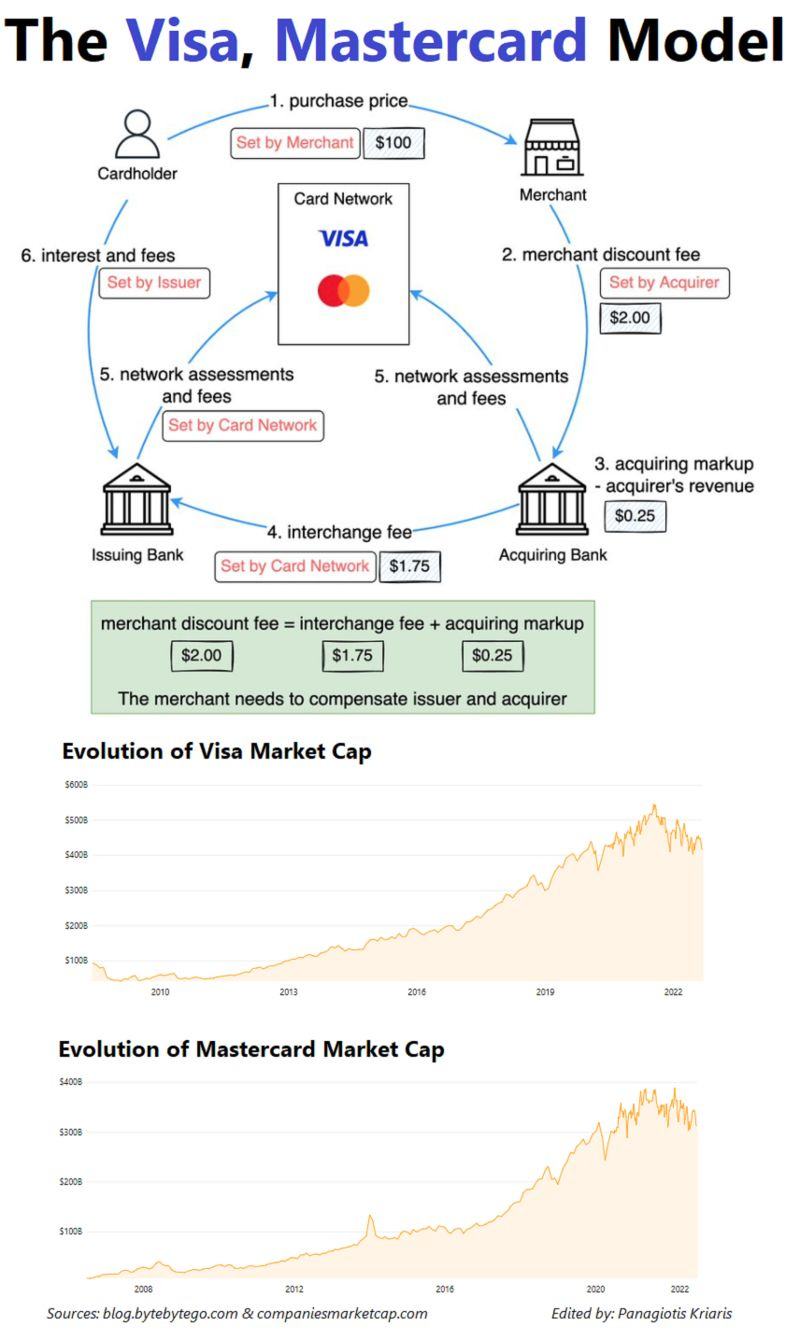

Their model is simple: Visa and Mastercard manage the rails that connect banks with customers. This middleman role allows them not only to define their access fees (the costs for routing a card payment through their network), but also the interchange fees that merchants pay to the card issuers.

It turns out that they more or less set their own fees, which vary from market to market. In the USA and Canada, these range from 1.5% to 3% of the purchase price. In the EU, where anti-trust rules have borne down on fees since 2015, the cost in 0.2% for debit cards and 0.3% for credit cards.

And their profit margins are, says Kriaris, just plain eye-watering:

Their astronomical margins (at 51.99% for Visa and 46.49% for Mastercard) come, therefore, as a little surprise. For comparison..., Apple, the globe’s most successful company has a net margin of 25.71%.

Their market capitalisation has also gone up quite a lot over the last few years. Visa is currently worth $416 bn, and Mastercard $311bn.

Some idle googling suggests that one of the reasons for this might be that they’re now able to live off earlier investment, as the New Zealand consumer regulator Jon Duffy suggested:

"And you've got to look at the value proposition. What are their overheads? To quote Flight of the Conchords, it's just money generation now, not a lot of systems building. I'm sure there's some maintenance but the profits will be astronomical compared to what what they're having to spend on products."

Margins of this size usually attract the attention of competitors, and of regulators. (The long run net return in most competitive markets is of the order of 10% or less.) Obviously the scale and the complexity of the infrastructure that makes all of this work, and the multiple parties involved, acts as a defence. All the same, Kriaris suggests that three things will erode these margins.

The first is that regulators are taking an interest, even in the United States:

the recently introduced Credit Card Competition Act wants to spur competition to the market and lower acceptance costs for merchants and consumers, via forcing banks to allow merchants to choose from at least two different card networks.

In the UK, where one of our many Brexit benefits was that we lost some of the EU’s constraints on the level of credit card fees, the Payment Services Regulator has launched a couple of market reviews into how the companies operate. These are likely to take a while: complexity is the oligopolist’s friend.

The second is open banking, which connects merchants and customers directly, and at a fraction of the cost of the two card companies.

The third is that there are alternative digital payment methods, and apps, that give merchants some leverage in this conversation.

In short, it is unlikely that either of these huge global companies is going to vanish overnight. But they’re unlikely to maintain those margins.

Other writing

Since it’s the weekend, let me mention that I have a review of the Dandelion Festival in Inverness published on the folk music blog Salut Live! Here’s an extract:

Despite the strength of the Spellsongs' set, the revelation here was the Siobhan Miller Band. She’s regarded as a traditional singer, for which she has been garlanded with awards, but listening to her and the band here this was a big sound—and an electric sound. The line-up behind her included guitar, bass, drums, keyboards and fiddle. It filled the space, and was a contrast to the mostly acoustic sound on her records.

j2t#371

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.