23 September 2021. Gig workers | Biomass

How gig workers are fighting back; all of the biomass on the planet

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: How gig workers are fighting back

When you look inside any digital economy supply chain, somewhere you find marginalised and underpaid workers, often working in dangerous conditions. So it is with the food delivery business, which has boomed, everywhere, as a result of the pandemic.

So it is not surprising to read in Restofworld.org that delivery riders are organising.

Singh, for example, started riding for the Indian delivery app Zomato in 2020, only to find that it became harder to make a living:

Whenever the app decided he was behind schedule, his phone would ring, and an automated voice would tell him to speed up or face a penalty. To make up the time, he’d take risks, darting up a one-way street or jumping a red light. During idle moments, the app would serve up videos telling him how to please customers by smiling and bowing. Sometimes, those videos would remind drivers not to speak to the media, which is why Singh asked to be identified only by his surname, for fear of being banned from the app.

Singh was off the road at the time of the interview, with his bike badly damaged in a collision with a drunk scooter rider while delivering a cake at midnight in Mumbai. And that had given him more time to spend on his twitter account, DeliveryBhoy, which calls out the sharp practice of the delivery companies, among other things:

Restofworld teamed up with a research company to try to quantify the experience of delivery workers, surveying 4000 gig workers in 15 countries, and added analysis from researchers, academics, and in-depth interviews. (They also approached six of the largest global platform companies, none of whom agreed to be interviewed).

The data shows that, while the experience of platform work is very local and takes on features of the societies and economies in which it operates, it’s also universal. Platform workers, whether they’re based in the U.S. or Nigeria, Indonesia or Ethiopia, are all struggling with a shared set of challenges: insecurity, anxiety, low wages, and high costs.

At the same time, however,

the common experience of precarious and often dangerous work has helped to create a genuine, global movement that is taking the fight to the tech companies.

It’s a long article, and I should credit the journalist, Peter Guest. It’s also part of a bigger project by the magazine, with profiles of gig workers—including drivers for companies such as Uber—in a host of countries that represents a real resource for people interested in this issue.

Rest of World spoke to riders and drivers in Ukraine, South Africa, Nigeria, Singapore, and India who all said the same: they had to be online for upward of 12 hours a day, simply to service the debt they’d taken on to work for the platforms. They weren’t in the majority — our survey shows that many workers do work less than eight hours per day — but on an hourly basis, 42% of the workers surveyed earned less than the statutory local minimum wage.

Platform companies operate in the way they do because they can—and dump their external costs on the societies they operate in. Their opaque algorithmic systems tend to amplify existing forms of discrimination. They use traditional anti-union rhetoric (for example, insisting that they negotiate with individuals, not with groups or organisations). And so far, their multinational base has made it hard for worker groups to get to grips with them.

It seems this may be changing.

But as conditions get worse, platform workers are increasingly getting organized. Among the workers surveyed by Rest of World, 48% said they’re now part of a formal group or union; 49% said they’d participated in strikes or other industrial actions. Among delivery workers, that rose to 59%. ... the workers’ movement (is) using globalized communications infrastructure to organize, meeting in international WhatsApp groups and Telegram channels, to share experiences, express solidarity, and coordinate their actions. The movement has become increasingly formal, and increasingly focused.

It’s impossible to write about delivery workers today without mentioning a piece in The New Yorker by Eric Lach. The photographer Johnny Miller (mentioned here before in the context of his Unequal Scenes project), now based in Williamsburg VA, filmed a delivery rider trying to make a delivery on an e-bike in the floods and torrential rains of Hurricane Ida.

Image: Johnny Miller

He sold this material to some networks, and decided to give the money to the rider he’d filmed. His journey to find him took him deep into the world of casualised delivery, of different ethnic groups of riders, and put him in contact with the riders organisation Los Deliveristas Unidos. It’s striking how invisible these workers are.

It’s a compelling piece, and I’m not going to spoil the ending here. But it comes like a punch in the solar plexus.

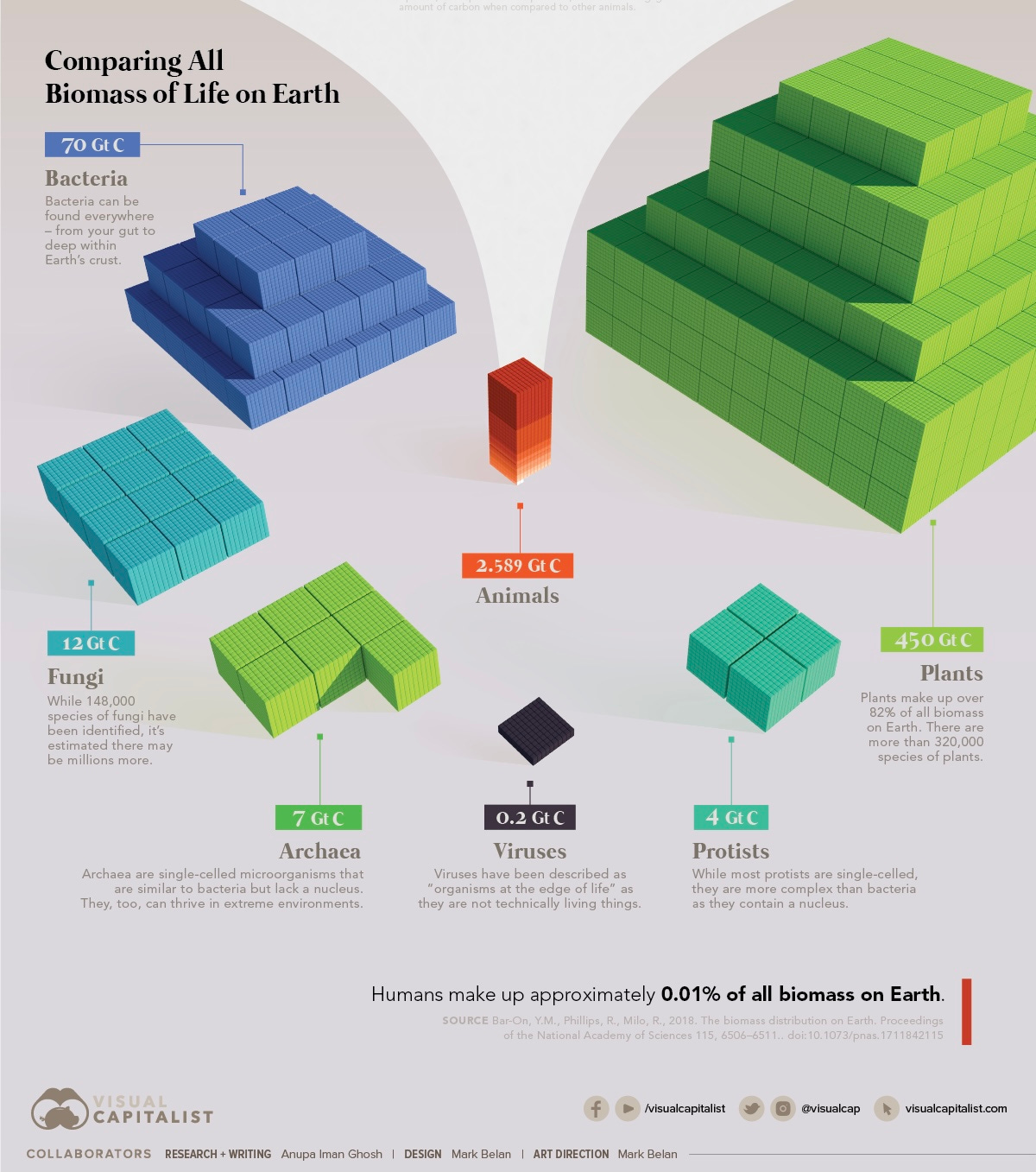

#2: All of the biomass on the planet

There’s nothing like a good infographic of all of the biomass on the planet to make you realise how trivial humans are, given how much damage we’re doing, and Visual Capitalist has just produced that infographic.

Actually, the way they present it rather overstates the weight of humans, so I have chopped it into two to improve the focus.

Here’s part one:

(Source: Visual Capitalist)

Humans are a fairly small part of that orange bit (‘Animals’) in the middle.

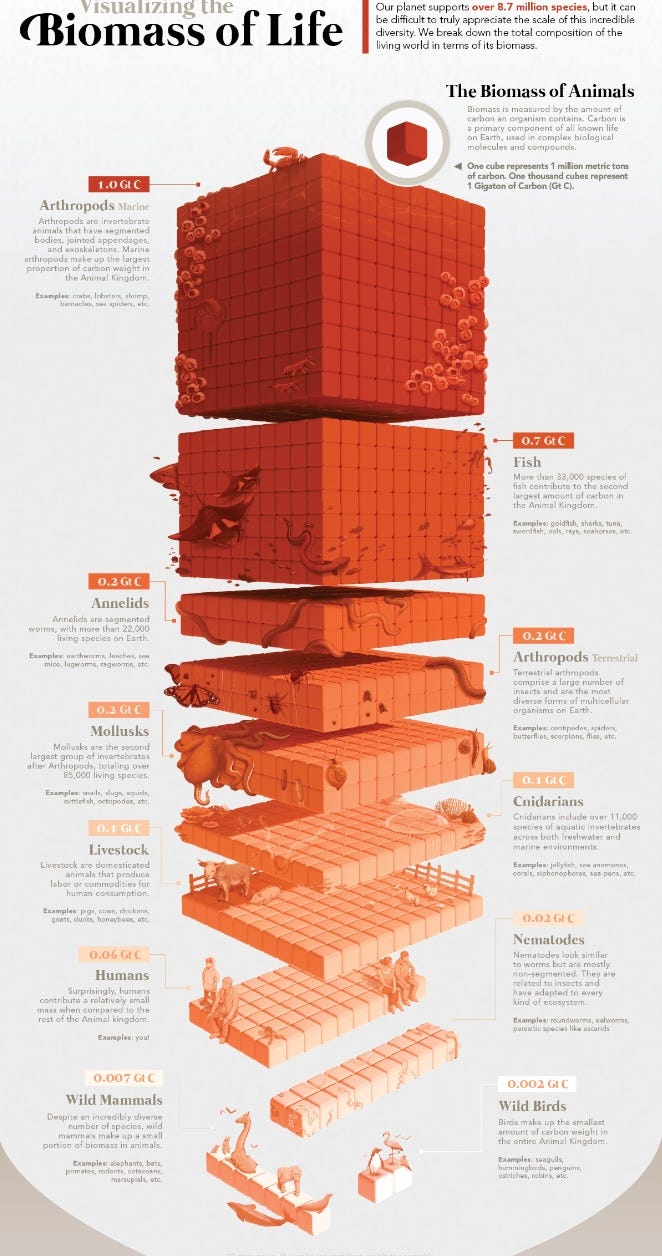

Here’s part two, which breaks out the detail of the orange bit. Humans are down near the bottom, between livestock, cnidarians, and nematodes in terms of overall biomass.

(Source: Visual Capitalist)

H/t Exponential View

j2t#173

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.