23 March 2022. Strategic futures | Business

Looking at strategy through a pair of Fred Polak glasses. The economic effects of ‘intangible’ capitalism.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

1: Looking at strategy through a pair of Fred Polak glasses

My colleague John Sweeney is a fan of the ‘Polak Game’, developed by the futurists Peter Hayward and Stuart Candy to spark conversations about futurists orientation. I used it as a starter in a workshop today, and in preparing for the workshop, I realised that—with a little modification—it could also be used as a strategy assessment tool.

But let’s rewind a bit. Fred Polak was an influential Dutch futurist who survived the Second World War in hiding, who turned his attention to rebuilding the Netherlands after the war. His book The Image of the Future (pdf), originally written in Dutch, was translated into English by Elise Boulding. (She taught herself Dutch to do it and the Bouldings invited Polak to California while she was doing ti to check on details, as I recall.)

It has a fabulous quote in it about the power of images of the future which has launched a thousand inspirational posters:

The rise and fall of images of the future precedes or accompanies the rise and fall of cultures. As long as a society's image is positive and flourishing, the flower of culture is in full bloom. Once the image begins to decay and lose its vitality, however, the culture does not long survive.

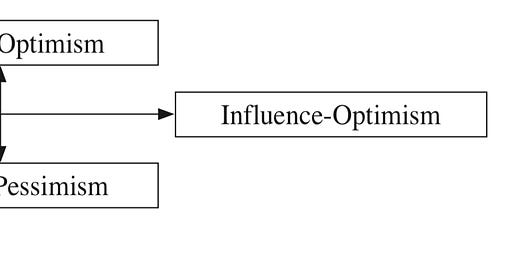

There’s quite a lot of discussion in the book about our attitudes to the future, that can be distilled, with a little interpretation, to two axes. (This is what Peter Hayward and Stuart Candy did in their paper in the Journal of Futures Studies.)

The detail is in the paper, but here’s the summary diagram:

(Source: Hayward and Candy, Journal of Futures Studies).

The ‘essence’ axis is about your expectation of the world: at the top, the overall trend is that it’s getting better; at the bottom, the overall trends is that it’s getting worse. The ‘influence’ axis is about what you can do about it—at the left, not a lot. At the right, you have quite a lot of influence.

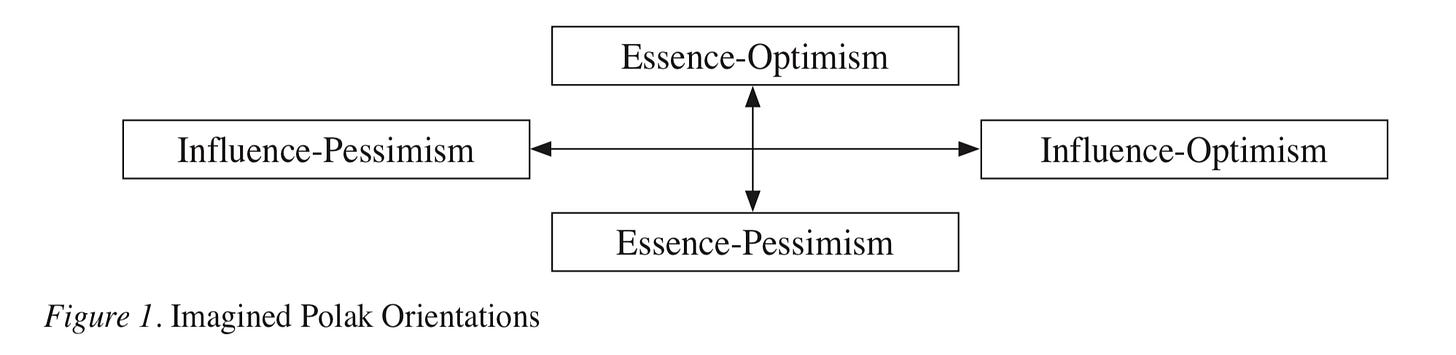

So, as you build this out, you get a 2x2 that looks like this. Again, the image is taken from their paper.

(Source: Hayward and Candy, Journal of Futures Studies).

In their work, they actually do this in the room—getting people to move to the quadrant of the room that reflects their view, and using that to start conversations within the four groups that emerge about why they feel like that, and also how they feel about the people in the other groups. In the paper there’s an interesting section on the self image of each group, and the language they might use to describe the other.

For example, the Upper Right group will often describe themselves as ‘powerful’; the other groups may perceive them as being ‘deluded’, or even ‘oppressors’. Similarly, the Lower Left group might think of themselves as ‘free’; other groups might think of them as ‘losers’, or ‘lazy’.

When deployed in an organisation the dynamics of the game can get very interesting. Once I worked with an executive group who all huddled in the UR, almost competing to be furthest into that optimistic-optimistic quadrant. As if channelling the UL’s critique, I asked: “How do you know you are not deluded?” When a group of decision-makers cluster in the UR, you can ask, “Where are your staff standing?” “Where are your customers?” The realisation may start to dawn that others are not necessarily energised by the same image of the future.

Peter Hayward, the co-author of the piece, says that he has found this most effective in trying to get people to agree on visions of the future—because it requires people to build some empathy with others about how and why they might feel differently about the future, before they build a vision.

For example, in a different futures conversation I had recently we were talking about images of space exploration. Clearly someone with a ‘To boldly go’ image of space as a Star Trek frontier is going to be a different quadrant from someone who is more sympathetic to Gil Scott-Heron’s song ‘Whitey’s on the Moon’.

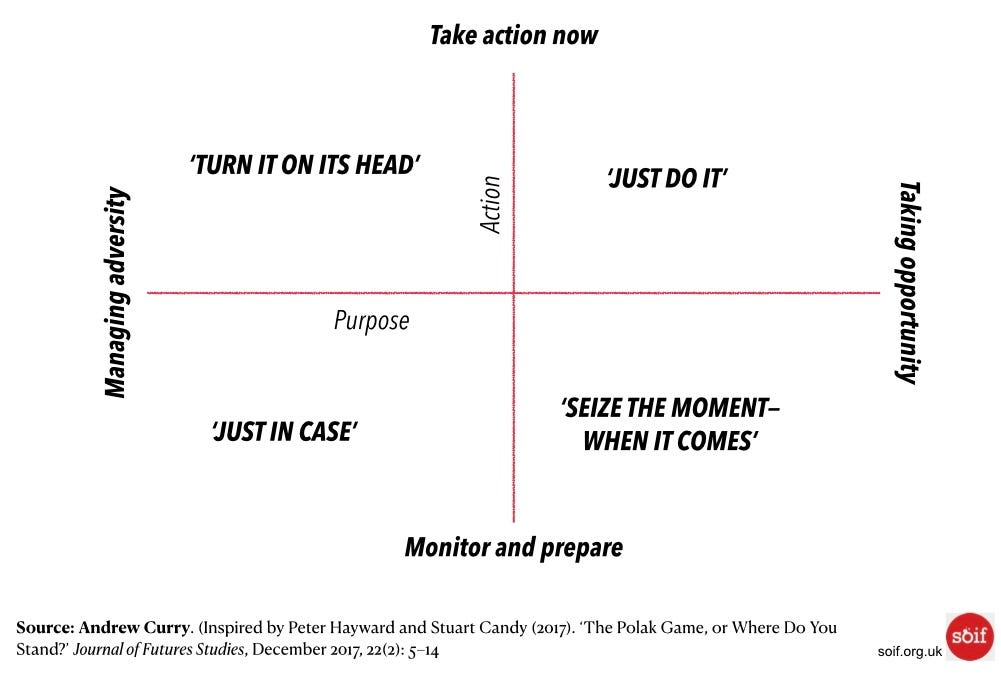

I was looking at this model as I was designing a strategic futures workshop and realised that—with a bit of adaptation—it might also map on a set of strategic perspectives that might help build more inclusive strategy.

In this version, the left-to-right axis is about purpose, and runs from ‘managing adversity’ to ‘taking opportunity’. The vertical axis is about the nature of action, and runs from ‘monitor and prepare’ to ‘take action now’.

(Source: Andrew Curry, inspired by Hayward and Candy, JFS).

So it’s worth running round the model to explain what each of the quadrants might mean for strategy. In the top left (managing adversity + take action now) I have called ‘Turn it on its head’. It’s about sources of abundance in the community that are currently regarded as a problem or a burden. So a council that has a problem with empty buildings, and turns them over to—say—artists on a peppercorn rent to see what happens, would be operating in this space. A lot of Hilary Cottam’s pioneering social design is also in this space.

Below it (managing adversity + monitor and prepare)—the ‘just in case’ space—are those things that you do as precautions. (The name at the bottom of this axis might not be right). Restoring or creating a water meadow in the expectation that both the number of floods and their intensity will increase is an example of ‘Just in case’.

Moving across to the bottom right—(monitor and prepare + taking opportunity)—is ‘Seize the time—when the moment comes’. This is about things that you can’t do anything about yet but can be anticipated: so you get ready. The famous story about Steve Jobs in 2000 or so, running an Apple that had narrowly escaped bankruptcy, waiting for the next digital technology wave, is an example of this. Similarly, you could have looked at the decade-long pattern of decline in price to performance of solar energy in 2008 or 2010, and known that it would reach grid parity sooner or later. When was inexact, but doing some preparation—in skills, pilots of technology and so on—would allow you to move when that moment came.

The top right quadrant is the simplest one; there are always things in a strategic futures analysis that are ‘imperatives’—they jump off the page at you. They are the easiest things to see.

It’s early days with this model. I don’t know how useful or not it might turn out to be. But—as with the Polak Game—looking at strategy through a Polak lens does mean that you end up thinking about the beneficiaries of strategic action in a different way. And maybe also have to spend a little time on questions of power, purpose, and distribution.

2: The ‘intangible’ economy is bad for our wealth

Stian Westlake and Jonathan Haskel have published a follow up to their book Capitalism Without Capital, and it is reviewed by Diane Coyle on her blog.

As she points out, there was a word missing from the title of the first book—it’s about the declining importance of physical capital to contemporary businesses, and the increasing importance of a whole range of intangible assets:

the point was to underline the relative importance of intangible capital in the economy now – everything from patentable drug formulae to reputation to social trust to the tacit know-how that makes complex organisations function. While intangibles have always been important in the economy, they now predominate in the creation of economic value.

The original book offered a model of how ‘intangible capitalism’ differed, based on ‘Four Ss’—scalability, sunk cost, spillovers and synergies. These pull in different directions. We’ve heard a lot about how firms based on software can scale rapidly, but less about the write-off of such ‘sunk’ assets if it goes out of business (unlike buildings or vehicles, that can still be sold.

Innovation is also hard to protect; yes, patents tend to work, but improvements in knowledge or processes tend to move around, spilling over to competitors. Synergies tend to exist, between hardware and software, and with physical investments. Warehouses are much more efficient when managed through digital logistics systems, for example.

If the first book was more analytical, the sequel is more about the policy implications of this intangible economy. Because, as we all know, our economies aren’t doing well at the moment. They suggest—by Coyle’s account—that we need new institutions:

They note... that investment in intangibles has slowed down markedly. Their diagnosis is that while existing institutions (in the broad sense in which that term is used in economics) were able to support intangible growth up to a point, progress now will depend on institutional reform: “institutions are out of sync with the intangible economy”. In their sights for reform are institutions and policies to support better (and fund) research and development, a redesigned competition policy, improvements to the financial architecture and monetary policy, and fixing cities.

Coyle is a self-critical economist with a strong interest in policy, and her short review suggests that this is another example of how the mental and market models of the last 40 years—individualism, “free” markets, and so on—are no longer fit for purpose:

Their fundamental point about institutions lagging the structure of the economy is spot on, as is the implication that different kinds of collective approaches are needed to the economy. In the world of the four Ss, individualism and market-knows-best policies make for stagnation and discord.

Ukraine notes:

There’s a fascinating interview with the French intellectual Olivier Roy at the European University Institute website that links the Russian attack on the Ukraine with Samuel Huntingdon’s theory of ‘the clash of civilisations’. The thing that jumped out at me was the idea that much of Putin’s ‘soft power’—certainly in the USA and the UK, and perhaps also in France—has been based on—successfully—fostering white grievance. But all of those gains have been destroyed by the military attack:

Putin's Russia was perceived by many conservative Christians (see the “Salon Beige” website for French Catholics) as the bulwark of traditional values, anti-LGBT and anti-abortion, whilst the Orthodox Church appeared as the champion of the reconquest of souls, in cooperation with the political power… Putin sacrificed all the soft power he had acquired over the last twenty years, which allowed him to be a global player, for a purely territorial vision of Russian power. The whole geostrategy of alliance with the populist right and Western religious conservatives, which made it difficult to exert pressure and sanctions against Moscow, vanished in thin air.

j2t#285

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.