23 August 2024. Digital | Plastics #597

Saving the data that matters // Jumping to conclusions about microplastics in the brain—well, it makes a good headline

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish two or three times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Saving the data that matters

We are generating more data than ever—even as individuals, let alone as organisations—but the formats we store it in are completely ephemeral, at least by any historical standards. That’s the paradox that sits behind a long article by Neil Firth in MIT Technology Review provocatively called ‘The race to save our online lives from a digital dark age’.

The phrase “the digital dark age” was coined by the physicist and computer scientist Danny Hillis, who is now part of The Long Now project:

Hillis, an MIT alum who pioneered parallel computing, thinks the rapid technological upheaval of our time will leave much of what we’re living through a mystery to scholars. “When people look back at this period, they’ll say, ‘Oh, well, you know, here was this sort of incomprehensibly fast technological change, and a lot of history got lost during that change,” he says.

The analogy is with the Early Mediaeval European period that was called the “dark ages” for quite a long time (though no longer, at least by historians) because of the apparent lack of sources.

(‘GeoCities has closed’. Source: Wikipedia.)

Firth starts his piece by tracing the digital history of a favourite photograph of his daughter, taken on a Samsung phone, the on a hard drive, then on an external drive, and now on Google Photos, to whom he pays $1.79 a month:

That’s a lot of trust I’m putting in a company that’s existed for only 26 years. But the hassle it removes seems worth it. There’s just so much stuff nowadays.

I imagine almost everyone reading this will recognise that data journey, and also will have things they worked on in the past that they can no longer access.

There is a couple of stories in the piece. The first is the risks of leaving things that we value in the hands of corporates who don’t value our stuff the way we value it. (To put it one way, we see it as use value, but they see it as exchange value: our incentives are definitely misaligned.)

The second is a story about increasingly sophisticated approached to storing data so it stays readable.

The first of these is more obvious, but more personal. And it has already happened:

MySpace, the first largish-scale social network, deleted every photo, video, and audio file uploaded to it before 2016, seemingly inadvertently. Entire tranches of Usenet newsgroups, home to some of the internet’s earliest conversations, have gone offline forever and vanished from history. And in June this year, more than 20 years of music journalism disappeared when the MTV News archives were taken offline.

There’s also no reason to assume that platforms that seem substantial will continue to exist—or, if they exist, will wish to keep on storing all that data.

Firth reminds us of GeoCities, an early web platform, which had been acquired by Yahoo, who decided in 2009 that they couldn’t be bothered to maintain it any longer:

GeoCities was famous for its amateurish, early-web aesthetic and its pages dedicated to various collections, obsessions, or fandoms—they represented an early chapter of the web, and one that was about to be lost forever.

As it happened, a group of volunteer archivists, led by Jason Scott, stepped in and saved a good proportion of the content over a period of six months or so:

He and the team ended up being able to save most of the site, archiving millions of pages between April and October 2009... Much was likely gone for good. “It contained 100% user-generated works, folk art, and honest examples of human beings writing information and histories that were nowhere else,” he says.

Scott now works for the Internet Archive, which is perhaps the most substantial attempt to maintain a record of the internet. The numbers are huge:

Its Wayback Machine, which lets users rewind to see how certain websites looked at any point in time, has more than 800 billion web pages stored and captures a further 650 million each day. It also records and stores TV channels from around the world and even saves TikToks and YouTube videos. They are all stored across multiple data centers that the Internet Archive owns itself.

The Internet Archive prioritises material that is most at risk of being lost, which mostly means print material that hasn’t been digitised yet. It also works with libraries to help them archive material.

The relatively rapid evolution of the internet and the worldwide web since the mid 1990s also means that things get lost because they are stored on unreadable formats. There are projects designed to fix this.

The Olive project, for example, builds virtual emulators for old and defunct software. The Long Now Foundation has created the Rosetta Disc,

a circle of nickel that has been etched at microscopic scale with documentation for around 1,500 of the world’s languages.

(The Rosetta Disc, storing the world’s languages. Source: The Long Now Foundation)

In a written culture, some kinds of written documents have critical value. Harvard’s Library Innovation Lab, has been working with courts and law journals to file copies of web pages at the Harvard Law Library, where they are stored indefinitely as a record of legal precedent. The US Library of Congress has proposed standards for storing video, audio, and web files so they are accessible for future generations.

The software company Github is storing some of history’s most important software, deep underground in Svalbard, in Norway, on special film that is designed to last more than 500 years. This includes the source code for Linux, Android, and Python. The same facility, the Arctic World Archive, stores data from the Vatican and the European Space Agency.

Microsoft Research, in Cambridge, UK, is working on a project that will create long-term storage on glass squares that can last hundreds of years.

Each one is created using a precise, powerful laser, which writes nanoscale deformations into the glass beneath the surface that can encode bits of information. These tiny imperfections are layered up on top of one another in the glass and are then read using a powerful microscope that can detect the way light is refracted and polarized. Machine learning is used to decode the bits, and each square has enough training data to let future historians retrain a model from scratch if required, says Black.

Of course, you need to include instructions for use. We argue about the speed at which to play back Charlie Chaplin’s early films because people simply assumed that the projection machinery would stay the same in the future.

A collection of issues bounce around in the article. The first is that corporations don’t care. Jack Cushman, of Harvard Library points out that if you use AWS to host your data, and you don’t pay your bill one month, your data has gone.

The second is that we can’t judge what might be regarded as important by future historians. It might be more valuable for them to have people share a slice of their data (their emails or photos for a week, for example) than trying to store everything.

The third is a theme about looking after data as part of being “a good ancestor”. (Vint Cerf, one of the founders of the internet, uses this phrase specifically). Some of these projects—such as The Long Now’s language disc—are clearly designed as cultural back-up devices.

But there’s a fourth thought here that goes unmentioned in the article. This is that we had better hope that these non-data storage devices work—the films, the discs, the glass. Because there’s at least one future out there where, from the perspective of a sustainable civilisation, the energy and water costs of maintaining data centres just become too high.

H/T to The Browser.

2: Jumping to conclusions about microplastics in the brain

The Guardian published an alarming looking story about the spread of plastic microplastics into the brain last week. The headline read:

Microplastics are infiltrating brain tissue, studies show: ‘There’s nowhere left untouched’.

On the face of it, this fits with everything else we know about microplastics: they are everywhere. On the other hand, a researcher at Our World in Data, Saloni Dattani, spent some time reading carefully the study which provided the data that sat behind the headline and the article. She’s not sure that it can take the weight that has been put on it.

Let me do the news version first.

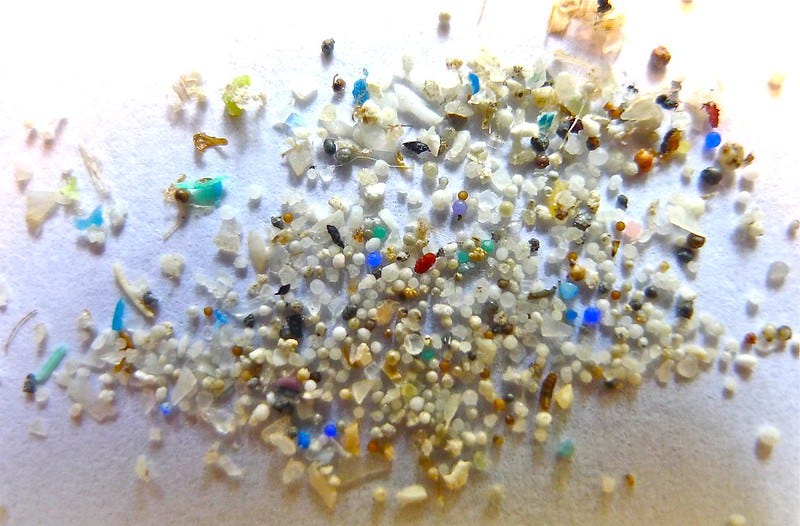

In one of the latest studies to emerge – a pre-print paper still undergoing peer review that is posted online by the National Institutes of Health – researchers found a particularly concerning accumulation of microplastics in brain samples. An examination of the livers, kidneys and brains of autopsied bodies found that all contained microplastics, but the 91 brain samples contained on average about 10 to 20 times more than the other organs.

This comes quite a long way down the article, which collects other data and reports on the microplastics problem. (Microplastics are defined as fragments smaller than 5mm in diameter.) Even just reading this as a one-time journalist, I had some misgivings.

The article starts this way:

A growing body of scientific evidence shows that microplastics are accumulating in critical human organs, including the brain, leading researchers to call for more urgent actions to rein in plastic pollution.

A couple of paragraphs later, we get one of these urgent calls:

Given the research findings, “it is now imperative to declare a global emergency” to deal with plastic pollution, said Sedat Gündoğdu, who studies microplastics at Cukurova University in Turkey.

(Microplastic. Photo: Oregon State University/flickr. CC BY-SA 2.0)

The article moves on to note the increasing numbers of studies on increasing levels of microplastics in animals, and references later a number of studies that suggest that microplastics are increasingly found in human bodies.

But it pulls up a bit short when it comes to effects:

The health hazards of microplastics within the human body are not yet well-known. Recent studies are just beginning to suggest they could increase the risk of various conditions such as oxidative stress, which can lead to cell damage and inflammation, as well as cardiovascular disease.

One of the reasons that this is structured like this is that the legwork has been done by a publication called The New Lede, which is a project run by the Environmental Working Group. It publishes its stories under a Creative Commons licence and encourages others to republish them.

The New Lede describes itself this way:

We are a news initiative specializing in coverage of environmental issues that are critical to the health and well-being of people everywhere.

It is a non-profit news organisation, and describes itself as non-partisan, but clearly (looking at its other stories) it has an environmental agenda. The Guardian’s use of its materials is a function of the fragility of the news sector these days.

Before I get to the study that drives the headline, I should be clear: I believe that the level of microplastics in species of all kinds is most likely increasing, and is much more likely to be bad for us than good for us. But the journalism in this article is a kind of belief-driven journalism. Because of my prior beliefs I nodded along with it, until I read Saloni Dattani’s critique on Twitter.

So let me get to the study that provided The Guardian with its headline.

It is published by a group of researchers in New Mexico in a pre-print by the National Institutes of Health, and has not yet been peer reviewed. They analysed two sets of samples of “de-identified, post-mortem human liver, kidney, and brain (frontal cortex) samples”, one from 2016 and one from 2024. Most of the organs that provided the samples came from the Albuquerque, New Mexico, office responsible for investigating “untimely or violent deaths.”

It’s worth noting that:

Most of the organs came from the office of the medical investigator in Albuquerque, New Mexico, which investigates untimely or violent deaths.

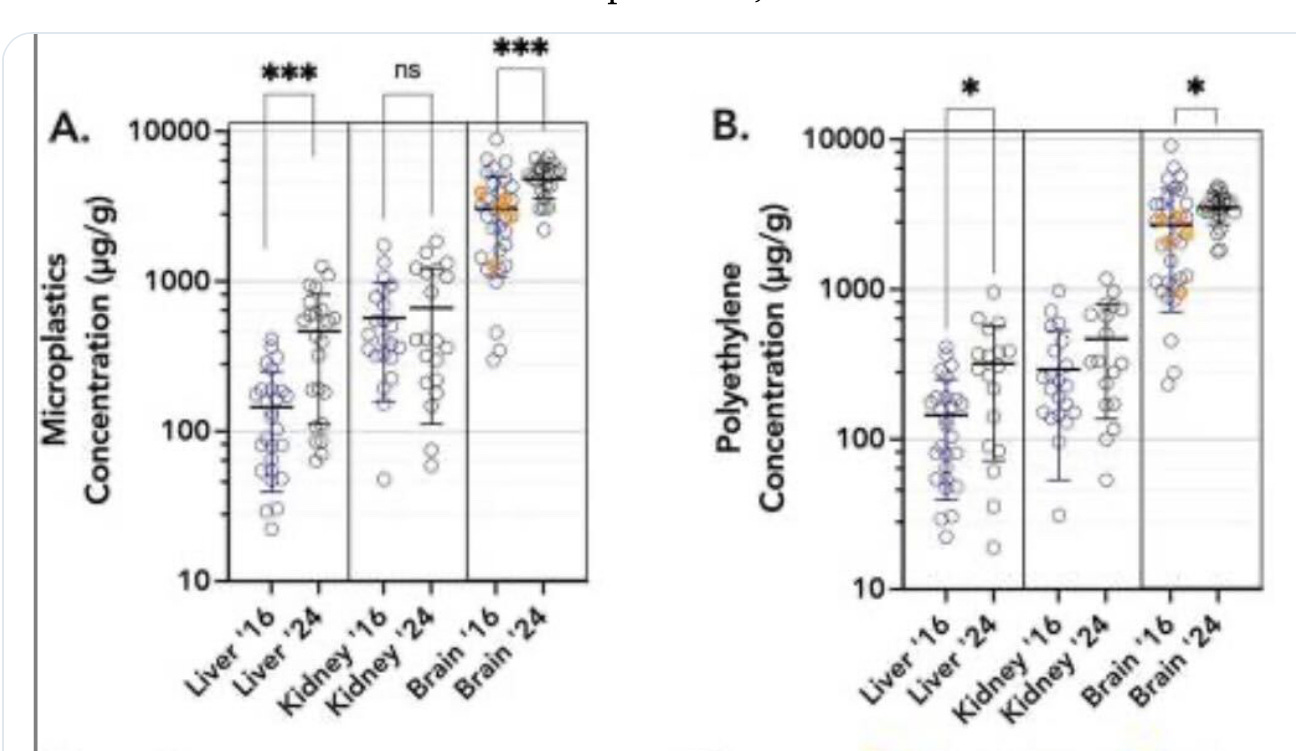

They found higher concentrations of microplastics in the brain samples than in liver or kidney samples. (This is from the paper). The level of microplastics in the 2024 brains was around 50% higher than the 2016 brains. This is possible: it is in line with the overall increase in microplastics in the environment.

The New Lede/ Guardian story quoted the lead researcher as follows:

“It’s pretty alarming,” Campen said. “There’s much more plastic in our brains than I ever would have imagined or been comfortable with.”... “I don’t know how much more plastic our brain can stuff in without it causing some problems,” Campen said.

The researchers also looked at 12 brains with dementia, including Alzheimers, and found that they had 10 times as much plastic by weight as healthy brains.

Since Our World in Data is a reputable research organisation, I thought it was worth reviewing Saloni Dattani’s critique of this.

She obviously notes that the article hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed, and that although the article suggests the prevalence microplastics is increasing over time, that’s an inference, given that we have only two data points. The information about Alzheimer’s isn’t in the referenced paper—the article says that isn’t yet released.

The sample sizes are quite small: 27 from 2016, and 24 from 2024:

That's seems fine for a preliminary study. But I question how much we can learn from these specific samples about microplastics concentrations across New Mexico, let alone at a global scale.

But the actual method of analysis seems relatively experimental, when you read the paper’s own statement of Limitations:

The present data are derived from novel analytical chemistry methods that have yet to be widely adopted and refined.

These have been designed, say the researchers, to deal with one of the problems of microplastics research, which is that contamination happens during the research process. There’s quite a lot of detail about why this might be in the Limitations statement, but it isn’t referenced elsewhere in the paper.

Dattani also looks at the charts in the paper, and notes that the 2016 brain samples have much more variation than the 2024 samples, while the kidney and liver samples from the two years have similar ranges, but this difference isn’t explained in the paper.

(Campen et al, (2024) Bioaccumulation of Microplastics in Decedent Human Brains Assessed by Pyrolysis Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry)

In response to her thread, another researcher, Oliver Jones, also noted that the method they used might just be picking up increases in types of fat in the brain.

[P]yrolysis GC (which is what they used) can give false results when used to measure plastics because saturated, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats give the same pyrolysis products as polyethylene leading to inaccurate measurements.

This piece is longer than I intended it to be. But it’s meant as a cautionary tale. Even when we think something ought to be true—and if it is true, it ought to be the proper subject of policy concern—journalism needs to tread carefully. At best, the New Mexico study is at present no more than a weak signal, the equivalent of a single pilot project in social research. At best, even if it passes its peer review with flying colours, it is a hypothesis that needs more research. It can’t carry all of the journalism that’s been laid on top of it.

j2t#597

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.