Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

The Euro 2021 tournament has prompted quite a lot of noise about the relationship between the England football team and English identity. One of the reasons is that the identity of the football team—urban and multi-cultural—is completely at odds with the ideas of English identity that are being stoked by the English nationalists who run the government.

One of the best pieces I read about this was by Natasha Chahal on the LRB blog.

Somewhere between Boris Johnson’s Brexit bus and the 51.89 per cent who voted to leave, I lost my identity. I’m a British Asian Midlander, raised in a Western household. I had always prioritised the British part over the Asian and the Midlander over anything else: I’m proud of being from Derbyshire... My culture is pints (a half of Guinness, if you’re asking), the English seaside, books by Alan Sillitoe, football. I had no need to question it and by the time I reached my early thirties I was comfortable in my brown skin. Until Brexit.

As she observes, Brexit forced her to confront her identity in ways she hadn’t expected, although this was tempered by her experience of the 2018 World Cup:

The visibility of players such as Raheem Sterling, Tammy Abraham and Marcus Rashford, all vocal advocates of social change, helped remind me of an England that had got lost among the tabloid headlines and expats complaining about immigration. I didn’t know if I could support an England that didn’t support me.

The England manager Gareth Southgate has had some plaudits for a piece published just before the tournament that reflected some of the same themes. Southgate’s always been clear that in the contemporary world football isn’t just about football.

Our players are role models. And, beyond the confines of the pitch, we must recognise the impact they can have on society... It’s their duty to continue to interact with the public on matters such as equality, inclusivity and racial injustice, while using the power of their voices to help put debates on the table, raise awareness and educate.

A report published by Better Future just before the tournament captures the moment that the view of the national team changed. An essay in the report by Sunder Katwala points to the 1996 Euro tournament as a decisive transition. The flag of St George became part of a shared emblem of the team, rather than one flown by a racist minority.

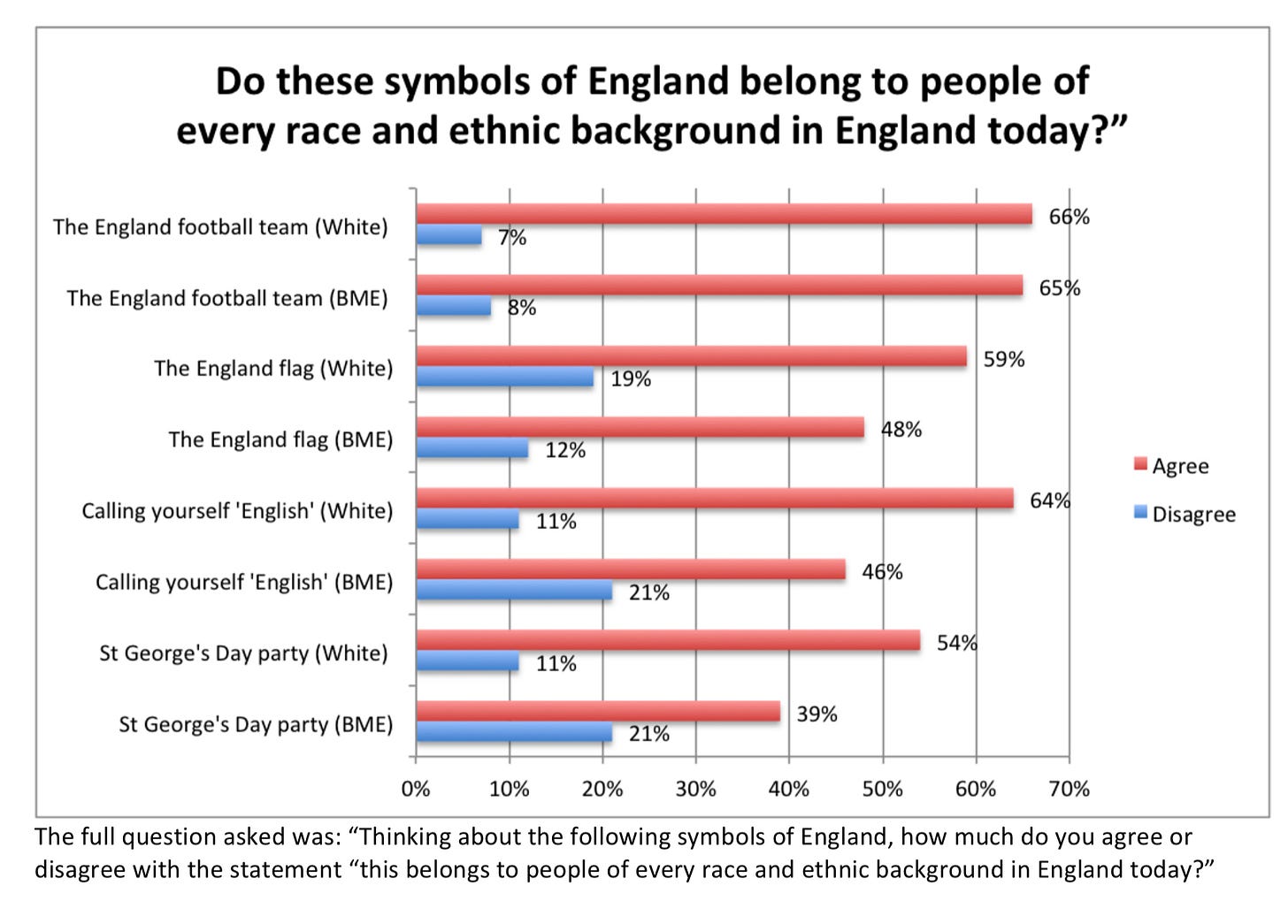

The question that’s put by the report is whether an inclusive English identity is possible outside of the stadium as well as inside it. Research for the report found that as symbols of English identity go, the football team is far more inclusive than others.

(Source: British Future (2021) Beyond a 90-minute nation: Why it’s time for an inclusive England outside the stadium.)

Some of the detail in the research also suggests that the St George’s flag is only inclusive when associated with the England football team, and not even then for many younger respondents.

And although the (British) national anthem is still played at the start of England matches, Katwala suggests that the 1996 tournament song, Three Lions, has come to represent the team rather more accurately:

The song rewrote the narrative of England’s football history. A dominant charge against English football had often been that of arrogance: that the country that invented the game had never come to terms with losing to foreigners. Yet Three Lions disrupts and rejects this notion. A tournament single sung from the viewpoint not of the players, but the fans, could reveal a different truth. England no longer expects.... Rather, supporting England involves a triumph of hope over experience... So Three Lions is an anthem that captures what it is to be a nation: the shared moments we experience together... 25 years on, Three Lions could even be understood as an English anthem about how to be at ease with being a middling power.

You can overstate this—it’s also the song that gave us the notion that “football’s coming home”. And the challenge is moving England—or the idea of Englishness—beyond being a ‘90 minute nation’. It’s a challenge that Scotland has met far more successfully:

England could learn from Scotland, once thought of as a ‘90-minute nation’. The Scotland of the 2020s is much less dependent on the vicissitudes of sporting success for its sense of status, both at home and abroad. In qualifying for Euro 2021, its team will not carry the burden of national identity that the Scottish teams of the 1970s and 1980s once did.

For Chahal, watching the England-Croatia game last week in a pub, even while reflecting on the deep racism experienced by several of its leading players, the identity of the football team gives her something to hold on to:

Not to support this team would be to shun the achievements and faces of Sterling and the other black players. To reject my stake in England’s national team would be to concede that England doesn’t belong to me. And it does.

#2: Under-used, mostly parked

Anna Rothnie, who’s a colleague on the work I do for DfT Futures, has a short video on LinkedIn talking about cars. Her brief from Mott MacDonald, where she works, was to talk about what sustainability meant to her, but she turned this on its head and talked instead about what unsustainability meant to her.

She goes through the numbers:

In the UK, there are more than 66 million people, and around 32 million cars. When they’re used, typically they carry one person rather than the five they are designed for. One of the comments adds that cars are parked on average for 95% of the time. Which is why they take up one-third of the space in cities. They also cost us £60 a week to run and kill or seriously injure 27,000 people a year.

It’s sometimes said that one of the purposes of futures work is to make the present strange, and listening to Anna present these numbers you realise how plain weird the normalisation of car culture is.

j2t#118

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.