22 November 2021. Racism | Productivity

Cracking racism in cricket—and elsewhere—involves dealing with the ‘bystanders’; why our obsession with productivity is an environmental curse

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: The role of ‘bystanders’ in racism

If you aren’t in Britain and aren’t interested in cricket, you might have missed the fact that the English cricket has been plunged into a deep crisis about its evident racism. The cricketer Azeem Rafiq—who has doggedly pursued a complaint about racism against Yorkshire County Cricket Club in the face of their repeated attempts to bury it—appeared in front of a House of Commons Committee to tell his story.

(Azeem Rafiq giving evidence to the UK Commons DCMS Select Committee. Photo: UK Parliament)

Many of the details are shocking, but what has been more telling has been the story of both the drumbeat of everyday casual racism, and everybody’s complicity in it. It’s difficult to believe, for example, that the then Yorkshire captain Gary Ballance thought it was acceptable in the mid-2010s to use the P***-word as a form of ‘banter’ between team-mates. (He hasn’t denied using the word).

And although the England cricket captain Joe Root (a Yorkshire player) gets a pass from Rafiq (“he’s never used racist language”), Root was clearly there when others were using it, without saying anything. Rafiq used this as an example of how normalised racist behaviour was in the cricketing culture:

“You had people who were openly racist and you had the bystanders. No one felt it was important.”

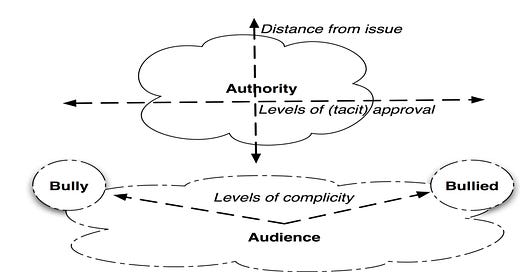

His language about bystanders reminded me of a framework (downloads pdf of book, p47 of 140) that my wife Sue Robinson developed with a colleague, Suki Macpherson, to think about cyber-bullying when they were working with young people.

Anti-racism campaigns, like anti-bullying campaigns, tend to focus on the racists (or, equivalently, the bullies). But if you take a systemic view, the role of the audience is critical.

And taking a systemic view, all bystanders aren’t equal. The article argues that there are four different types, and the mix determines the culture.

Starting closest to the bully, these are as follows:

- The Sidekick: “The sidekick enjoys the bullying and encourages and exacerbates it from the sidelines... Their support and involvement sustains the bullying and enhances the self-esteem of the bully.” In Rafiq’s testimony, Alex Hales—who allegedly named his black dog ‘Kevin’ after a name used as a generic name for black cricketers by Gary Ballance—comes across as a sidekick.

- The Satisfied Watcher: “This person does not actively participate in bullying. They look on at the actions of the bully, reading posts, perhaps laughing and enjoying the experience.”

- The Immobilised: “Often, this person is perplexed and worried about what is happening but feels immobilised to stand up against the bully and sidekick(s)... (they) often do not know how to act in response.”

- The Active Critic: “Members of this group are likely to intervene to stop being bystanders and take action... They have feelings of shock, sadness or disgust, which provoke them to action.”

In terms of the diagram, these four types range from left to right, with the Sidekick close to the Bully, and The Active Critic close to the Bullied. When there is an effective group of Active Critics, the Immobilised group can find a voice.

And it’s also worth noting that this doesn’t usually play out in private. There are always authorities in the system, who may, or may not, get involved. Levels of approval of bullying, and levels of complicity, are high to the left, and low to the right:

The audience plays itself out between the bullied and the bully under the aegis of an authority or authorities who will have a tacit view of the degree of acceptability of bullying and a greater or lesser distance from its incidence (see figure).

In terms of both Yorkshire County Cricket and the ECB (England and Wales Cricket Board), it is pretty clear that Yorkshire was completely complicit in condoning racism, while the ECB chose to be too far away to make a difference. (It allowed Yorkshire to hold an internal inquiry into Rafiq’s allegations, because Yorkshire told the ECB that this was what wanted to do. Really.)

One of the issues here might be that elite sportspeople tend to need to bond around a set of norms to be effective as a competitive team—but that they’ve clearly bonded around the wrong set of norms. Yorkshire appears to be only the worst example of this, and that might just because Rafiq has been tough enough to see it through rather than folding.

But if cricket is going to fix this, the authorities and the players need to find ways to deter the behaviour of the sidekicks and watchers, and support the active critics. In a sport marked by a combination of significant privilege and institutional racism—4% of professionals are British south Asian, against 30% of recreational players—it’s going to be a tough process.

#2: The idea of ‘productivity’ is an environmental curse

A short piece on Medium by Adam Lent suggests that we should be grateful that Britain’s productivity is low.

The conventional wisdom on productivity—effectively the value created by each worker—is that we need more of it. Higher productivity enables greater social spending, or creates the opportunity to work less while earning the same amount. But it is also leads to more stuff:

Contrary to widespread opinion, improved productivity does not lead to less use of material resources in the production process, it leads to more — much more. The reason is simple. Higher productivity means products can be made more cheaply which allows more of them to be sold. Equally it means existing products can be enhanced with the use of more materials without a consequent rise in price.

Now, this version of events is contested by some economists. They say that we’re starting to see some disconnection between resource use and productivity. But Lent quotes Vaclav Smil’s data on mobile phones:

(W)hereas mobile phone ownership was once reserved for the minority, the world is now awash with phones. As a result, the environmental scientist, Vaclav Smil, estimates that while the average weight of an individual phone may have fallen from 600g in 1990 to 118g in 2011, the overall weight of all mobile phones in use rose from 7,000 tonnes to 700,000 tonnes over the same time period.

(The material weight of mobile phones. Photo by believekevin/flickr, CC BY 2.0)

And you can see the same phenomenon everywhere:

The overall result has been a growth of all the materials used in the economy from around 8 billion tons per year in 1900 to around 90 billion tons today — a figure that is still rising and accelerating rapidly.

And to put that in context, that’s a 11-fold increase in materials, against a three-and-a-half-fold increase in population over the same period. And, as he notes:

It is this unceasing expansion of material use that is destroying the planet.

Lent thinks that economists are still trapped in a mindset that developed before the extent of the environmental crisis. There are things they can do to change this.

You could, for example, ensure that the benefits of productivity gains were taxed to provide environmental goods. And you could broaden the notion of economic ‘welfare’ so it focussed more on wellbeing, once basic standards of material welfare are met. Economists do discuss this—but not mainstream economists.

Adam Lent doesn’t mention it, but one of the other reasons that productivity may be falling is because services are becoming a more important part of the economy. Generally, it’s hard to improve productivity in services without making the service worse. (Think about ‘raising productivity’ in a care setting by having carers visit 16 people a day rather than 10, say). The economic theory on this was developed by Baumol, and is known by economists as ‘Baumol’s cost disease’. Language always gives you away eventually.

Update: For anyone who got engaged in the piece on Friday on versions of Beowulf, Tolkien’s version (probably the most literal) translates ‘Hwaet’ as ‘Lo!’.

j2t#212

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.