22 June 2022. Politics | Genetics

The nature of freedom. // ‘Hard work’ may be a product of your genes

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. And comments are open.

It’s a bit of a books edition today.

1: The nature of freedom

Lea Ypi’s book Free: Coming of Age at the End of History has been a surprise hit. We should probably ask why: my first thought was that at the distance of three decades there is a certain exoticism about a childhood in the most zealous Communist regime in Europe. Albania’s Communist government collapsed when she was 11.

But it’s also because of the way she writes it, through her eyes at the time when the story unfolds. Everything is taken, apparently, at face value, whether by the 11-year old girl in the Pioneers or the 18-year old who lives through the Civil War.

(Image: Penguin Random House)

She is a child of parents who both have ‘biographies’, who are always going to be outside of the Party because of their background, and who have an elaborate set of codes to talk about friends and acquaintances who are in camps or in jail—and their deaths or deportation.

Equally, she describes at face value the explanations of how the world works presented in class by her primary school teacher Nora. And, similarly, of the many reasons why there isn’t a picture of the late leader ‘Uncle’ Enver in the house: the one they had was too small, or of poor quality, or needed a new frame, and so on.

Or puzzling with her friends over the glimpses of English food shopping seen on the Albanian TV programme Foreign Languages at Home. What are the trolleys for? Where are the queues?

And then in 1990 it all comes stumbling into the sunlight. The first edition opposition paper that appears in 1990 has an editorial on the importance of truth:

”Only the truth is free, and only then does freedom become true”.

But people queuing to buy it still took empty milk bottles with them as alibis in case the secret police asked them what they were queuing for.

And some of these truths are quite hard to learn. The hated pre-war “quisling” Prime Minister Xhafer Ypi, whom the Party insisted had handed the country over to the Italian fascists at the start of the war, turns out to be her great-grandfather, a fact her parents had hidden from her; hence her father’s poor ‘biography’.

Her mother, from one of Albania’s pre-war business dynasties, throws herself into the politics of the democratic transition, preaching the “shock doctrine” at rallies. But even her things aren’t what they seem. She also plays European civil society groups at their own game, raising funds for ‘women’s study tours’ that actually enable Albanian women to see their children and relatives in other European countries for the first time in years.

Indeed, the whole eight year narrative is—hence the title—a biographical exploration of what freedom means that is painted in shades of grey.

Her father, for example, loses his forestry job when the Communist state collapses, gets another one after a while running one of the new market-based enterprises. His success at reducing its debt leads to another job running Albania’s largest post working with a Dutch World Bank expert who has lived everywhere and nowhere. (The locals nickname him ‘The Crocodile’, because of the logo on all of his short-sleeved shirts.) But her father finds it impossible to make redundant the members of the Roma community who have worked at the port for years, and who take to pleading for their jobs in his garden.

And communal life in Albania wasn’t unremittingly bleak. When Mr World Bank moves to the neighbourhood, the neighbours throw a big traditional Albanian party to mark the occasion, which everyone enjoys except for him. And, before 1990, there was a rich array of clubs: “poetry, theatre, singing, maths, natural sciences, music, or chess”, which had closed abruptly when the Communist government collapsed.

Then there is the civil war in 1997, which has to be read as a symptom of “structural reform” and economic shock—and as an effect of the unregulated collapse of the Ponzi-driven savings companies in which many Albanian families lost their savings, including Ypi’s family.

The same unfolding of the narrative follows the fate of her friends and neighbours. Elona, a bus drivers’ daughter, ends up being trafficked for sex in Italy. Flamur, the neighbourhood bully, shoots his brains out by accident while playing with a gun during the civil war.

So to come back to the question I asked at the beginning: why is the book a critical success right now?

I think it is because we have had long enough since the the fall of the Berlin Wall to see the whole cycle. From the Communist regimes to the “structural reforms” and the “shock therapy” that followed, and all of the ugly crises that this created across Russia and Eastern Europe. In Albania, that meant civil wars and refugee boats to Italy, some of which sank during the crossing.

It wasn’t the end of history after all—I’m sure that the sub-title of Free is meant ironically. It would be hard to match the deliberate cruelties of the Albanian regime, but the incidental cruelties that were a direct and indirect result of privatisation and structural reform were neither trivial nor casual.

This isn’t attempt at equivalence or equivocation, but a simpler thought: that all political systems include elements of violence. And we aren’t really free to choose the types of political or economic violence that we prefer.

Ypi’s mother ends up in Italy with her brother, cleaning and caring. Her father dies of asthma in Tirana, from the city’s pollution, having moving there to look for work. (The family comes into some money when it is able to reclaim some reasonably desirable land confiscated by the Communist government).

And Lea Ypi’s ‘biography’ here turns out to enable her to navigate through these transitions, and what freedom means within them. The evident hero of the book is her grandmother Nini, who has clearly lost the most. She was the daughter of an Otttoman pasha and had attended King Zog’s wedding; she had had the chance to leave Albania but had declined; her husband, Xhafer Ypi’s son, was a socialist who was jailed for 15 years for ‘agitation and propaganda’.

My grandmother was not nostalgic for her past... She was aware of the privilege into which she had been born and suspicious of the rhetoric which justified it. She did not think class consciousness and class belonging were the same thing point she insisted that we do not inherit our political views but freely choose them, and we choose the ones that sound right, not those that are most convenient or best serve our interest."We lost everything," she said, "but we did not lose ourselves. We did not lose our dignity, because dignity has nothing to do with money, honours or titles."

Lea Ypi is a Professor of Political Theory at London School of Economics now, and teaches and researches Marxism. A cousin, she says, remarked

“that my grandfather didn’t spend fifteen years locked up in prison so that I could leave Albania to defend socialism.”

But thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, and after thirty-five years of neoliberalism, questions of what it means to be free are more alive, and more problematic, than ever. And, along the way, it’s a delight to read, and often quite funny.

2: ‘Hard work’ may be a product of your genes

Peter Curry has a long review-cum-discussion of Kathryn Paige Harden’s book The Genetic Lottery at his newsletter King Cnut. (By long, I mean around 5,000 words’. It’s in six sections, and with his permission I have pulled out one of the sections here.

Every so often a certain news story repeats itself. A rich celebrity, or business leader, or influencer, makes a comment like: “I've worked my absolute a** off to get where I am now.” That was Molly Mae-Hague, a successful instagram influencer, who took a lot of heat for the Thatcherite tone of her comments.

Kim Kardashian infamously made a similar comment:

I have the best advice for women in business. Get your f*cking ass up and work. It seems like nobody wants to work these days.

She later apologised for this comment, but even in her apology did not shy away from her core message, that she has earned her position by hard work:

Having a social media presence and having a reality show does not mean overnight success. And you have to really work hard to get there, even if it might seem like it’s easy and that you can build a really successful business off of social media and you can if you put in a lot of hard work.

There is an almost infinite list of such ideas drifting through the internet, all revolving around the idea that anyone can work hard, and it’s the difference in the amount of hard work that people do that justifies wealth inequalities.

The traditional left-wing counter-argument to these stories is to label such ideas as ‘Thatcherite’, and to point out that those at the top sit in a nexus of socioeconomic privilege and advantage which is difficult for them to see, adroitly summarised in this cartoon. That nexus of privilege enables these people to work hard, and to work hard at things that enable bigger rewards, such as unpaid internships, or orchestrated sex tapes feat. Ray-J (click the link, I dare you). The point about privilege is legitimate, but if we accept Harden’s conclusions, and again, that’s a big ‘if’, we should also make a secondary point, about the inequity of genetics.

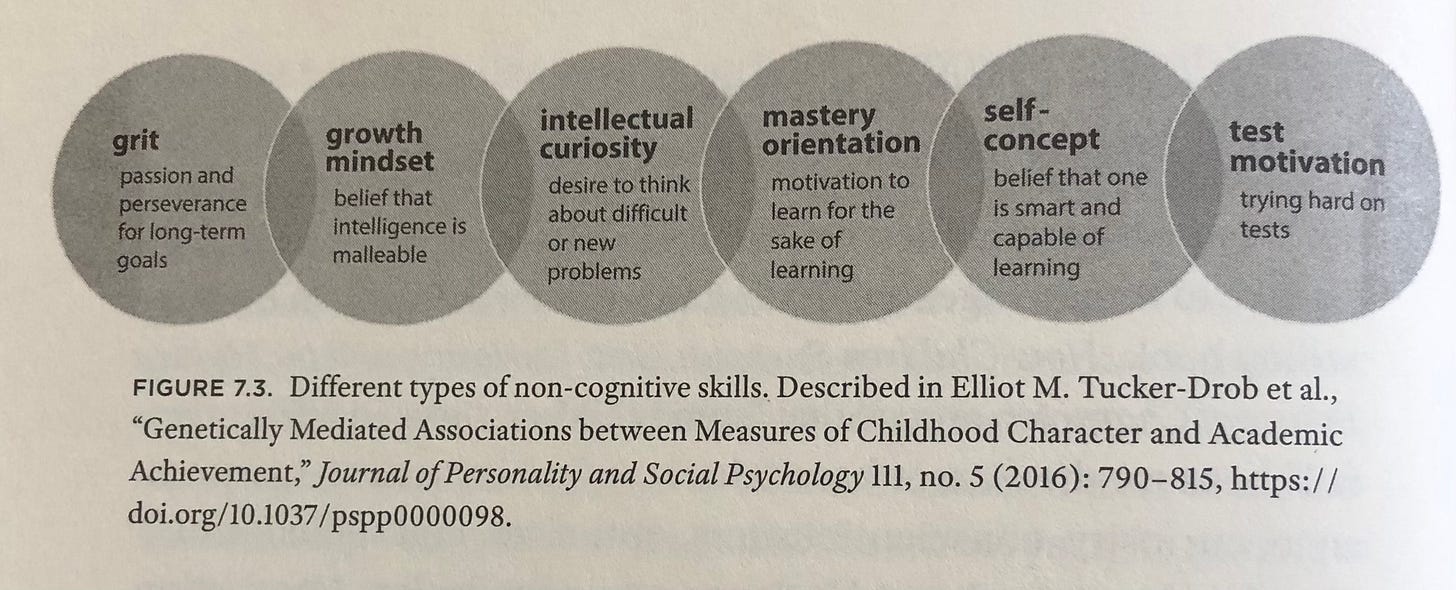

Geneticists and neuroscientists spend a lot of time debating a set of skills known as non-cognitive skills. The title is a misnomer, because most of the genes and neurons involved in the development of these skills are instantiated in the brain. You’ll almost certainly recognise some of them because they spend a lot of time in the public eye being pushed by various psychologists and educational reformers:

These are taken from a paper by Tucker-Drob et al. (et al. here including, the protagonist of this story, Kathryn Paige Harden) on non-cognitive skills. ‘Hard work’, the concept that the influencers above love so much, is perhaps most closely reflected in ‘Grit’, or the ability to keep going even while surmounting difficulties. But all of these non-cognitive skills are likely to be relevant to the ability to work hard…

Tucker-Drob et al. suggest that all of these skills are moderately heritable (~60%) in the same way that cognitive skills are moderately heritable (~50-80%). All of which suggests that a significant amount of your ability to concentrate, your ability to focus, your ability to sit there and not get distracted by Candy Crush, or Facebook, or a slot machine, or a bird, or Superman, is genetic in origin. Or rather, your ability to focus better—relative to your peers—is partly genetic in origin.

To put it yet another way, differences between people in their ability to work are not immune to the randomness of genetics. Genetic and environmental randomness play large roles in determining people’s skillsets, and importantly, their ability to work hard, sustain their concentration and avoid distractions. Tucker-Drob et al. focus on the ability to succeed in academic environments, but there’s no reason the ability to apply yourself in a disciplined manner wouldn’t be present in other places. Justifying wealth inequalities off the back of these skills is thus a deeply damaging idea. Life isn’t as simple as saying “I work hard, so I deserve this”.

j2t#334

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.