22 July 2022. Google | Time, again

Google as the new Raj of news media. // The limits of timelines

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Have a good weekend.

1: Google as the new Raj of news media

The recently launched European Review of Books has put an article online about the dependency of publishing on Google. As Alexander Fanta writes:

Say we start a magazine, let’s call it The European Review of Books. To get started, we need to collaborate on our manifesto – let’s use Google Docs! Later, to announce our launch, we post a video to YouTube. To keep things simple, our site is hosted on Google Cloud and built with Newspack, Google’s web design tool. We ask readers to contribute via Subscribe with Google. And to earn a little cash, we sell banner advertisements through Google Ad Manager.

He suggests that this network of relationships has just evolved, rather than been designed, and that Google has had failures along the way. One result is that it’s difficult to characterise the relationship between print publishers and Google:

It is not easy to understand the role Google plays, or for that matter what Google even is: partner, competitor, benefactor. Journalists, publishers, regulators, and scholars are left grappling with our new, random god.

The piece takes a long view of this, discussing the launch of the London Review of Books during the year-long strike at Times Newspapers in the 1970s, when the magazine was laid out with cowgum and a fair bit of tippex. And the limits, or perhaps fragility of newspaper conglomerates such as News International and Axel Springer. Which takes us back to Google again.

Today, Google is the world’s foremost meta-publisher. It has turned online advertising into one of the most profitable businesses on earth, with itself the primary beneficiary... With a share of 92 per cent of all European searches, Google remains the single most important driver of visitors to news websites – for some it brings a quarter of all traffic. Publications large and small now submit to the discipline of « search engine optimization », a strange new cottage-industry. Newsrooms hire teams of specialists to make inane guesses on how to game Google’s search algorithms.

And although readers donate more than they used to journalism, and philanthropy has kicked in, Google is the largest supporter of journalism:

Foundation funding for journalism has risen steadily over the past decade; the Press Gazette has calculated a global increase from 105 million US dollars in 2010 to at least 421 million in 2020. The donor list boasts fixtures of the international world of philanthropy – the Ford Foundation, George Soros’ Open Society network, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation – but the largest single funder of journalism is Google.

This has been a strategic response by Google to pressure on the company caused by its own success in extracting advertising revenues from the newspaper industry. Fanta traces a thread that starts in France in 2013, when Google agreed to create an innovation fund for French news media, and was then quickly extended to elsewhere in Europe.

(Image via pxhere.com. Public domain)

Since then, Google has channelled some 200 million euros into European news media, along with funding for training, academic research, and industry conferences. Critics get co-opted. In turn, this affects the discourse about news media.

The tech companies’ most important achievement has been not to influence what is reported about them but to alter the boundaries of debate around the journalism's business models. The publishing business has come to accept rather than challenge Google’s gatekeeper role over online publishing as natural; it has internalized this product of Silicon Valley empire-building.

Fanta acknowledges that he has also been a recipient of Google’s money, which included a six month stint as a researcher at the Reuters Institute, itself part-funded by Google. Google didn’t interfere with his research (about innovation) or, as far he could see, seek to influence the wider agenda of the organisation. Which left Fanta with a question: “why pour so much money into journalism?”, which he explored with Ingo Dachwitz:

We found that Google has used its funding as a strategic instrument to court publishers, and to allay worries over emergence as a sort of operating system for journalism. But we kept bumping into the conceptual difficulty of naming Google’s magic money tree. Even the Google managers we interviewed couldn’t quite say whether we should call it philanthropy, lobbying, or something else.

So far, there has been little research into the effects of this dominance of the sector; Fanta found that people were surprisingly uninterested in its effects.

It’s hard to characterise it. Google isn’t a media mogul, interested in acquiring titles, nor is it trying to influence the sector through the weight of advertising. Google’s presence—or that of Facebook/Meta—in the media ecosystem doesn’t seem to have much curtailed investigations into the power of Big Tech. Fanta concludes that what Google is doing is, in effect, a form of market management:

Rather than influence what the press reports, Google harnesses the how as a horse for its money-making plough. The threat it poses is not primarily to editorial independence, but to economic autonomy. It thrives on a news ecosystem with different sources, all producing fodder for its search engine and more online real estate to place advertising.

One way of thinking about it might be as a form of capture, an idea developed by the the scholar Efrat Nechushtai, who looked at the tech companies’ control over the infrastructure of news media:

«Facebook and Google,» she observed in 2017, «now influence all three stages of news production: internal and external communications, tools and platforms for crafting stories, and platforms for news distribution.» In Nechushtai’s view, this limits the press’s capacity to exert a quasi-regulatory check on the powerful and could allow the tech giants to put pressure on journalists.

It’s a long piece, and I’m not doing the detail any justice here. But if it is a form of regulatory capture, then it requires a regulatory response, and we have started see this kind of response from the European Commission. But the billions of euros of fines levied on the tech giants for anti-competitive behaviour so far has had little effect.

Fanta has a view on why this has had little effect. He thinks we’re using the wrong metaphors to understand the role and power of Google here:

(W)e are dealing less with a form of insider trading or regulatory capture, than with something both more novel and more archaic. Our historical analogy should not be Wall Street, but the British Raj. We are witnessing the passing of the guard from the moguls of old to the new colonizing power.

He extends this metaphor into some of the deals made by even the largest media companies, such as Axel Springer and News Corp with Google Facebook. Mathias Dopfner of Springer, and also the chair of the German publishers’ association, used to be a critic of Big Tech. No more: he had a celebrated rapprochement with Mark Zuckerberg in 2019:

(I)n a chat with Zuckerberg in Berlin, a neatly produced video of which can be found on Facebook’s corporate news site, Döpfner comes across less as an outspoken critic of Big Tech than as a local chieftain seeking to extract concessions from his new digital ruler. «I hope that you want to be a neutral platform that helps that ecosystem to generate money also for others and have that plurality».

And similarly, Murdoch, who has agreed to a global licensing deal for his content with Google said to be worth $50 million a year, which seems on the cheap side to me. The detail seems less important than the tone: “historic multi-year partnership”, etc etc etc:

With this sweetheart deal Murdoch, who previously attacked Google and Facebook sharply, has effectively bound his business in an ever-closer union as a supplier to the giants’ content-processing machine – a subservient position that, once assumed, will be hard to escape from.

2: The limits of timelines

After I published the piece on time and timelines this week, Richard Sandford sent me an article by Daniel Rosenberg called ‘The trouble with timelines’. It was published in Cabinet magazine almost a couple of decades ago.

There are some immediate points of interest.

The first is that Joseph Priestley wasn’t the first to publish a timeline (in 1765). That honour goes to

Jacques Barbeu-Dubourg’s 1753 Chronological Chart and earlier roots in chronologies and genealogies, calendars and canon tables, and traditional forms of narrative imagery depicting historical events.

The second is that, all the same, when Priestley published his timeline, the concept was sufficiently strange to need defending, even explaining:

the idea of a timeline was still strange enough in the mid-eighteenth century that it required a certain amount of explanation. In his accompanying pamphlet, Priestley argues that although time in itself is an abstraction that may not be “the object of any of our senses, and no image can properly be made of it, yet because it has a relation to quantity, and we can say a greater or less space of time, it admits of a natural and easy representation in our minds by the idea of a measurable space, and particularly that of a LINE.”

The idea caught on, perhaps because of its simplicity—the visual reference of time as a line is easy to grasp, after all. But that brought its own problems.

History had never actually taken the form of a timeline or of any other line for that matter. And simplicity, the great advantage of the form, threatened also to be its greatest flaw... (A) century later, Henri Bergson would refer to the “imaginary homogeneous time” depicted by the timeline as a deceiving “idol.”

But even in Priestley’s time, the notion of time as a straightforward progression was being undermined. Laurence Sterne’s book Tristram Shandy, which was published in successive volumes between 1759 and 1767, made much of digressions and deviations:

For Sterne, the linear representation of time is a construction. “Could a historiographer drive on his history, as a muleteer drives on his mule,—straight forward;—for instance, from Rome all the way to Loretto, without ever once turning his head aside either to the right hand or to the left,—he might venture to foretell you an hour when he should get to his journey’s end,” Sterne writes. “But the thing is, morally speaking, impossible.”

The novel even includes timelines of Tristram Shandy’s journey, which are as much wiggle as line.

(Source: University of Utah Library blog)

There seems to be something of a cultural and technological history here, since as the idea of the timeline became more normalised, so the technology required to sustain their increasing complexity also became increasingly complex:

Dubourg’s Chronological Chart, mounted on a scroll and encased in a decorative box, was already fifty-four feet long. Later attempts to re-anchor the timeline in material reference, as in the case of Charles-Joseph Minard’s 1869 diagram, Figurative Chart of the Successive Loss of Men in the French Army in the Russian Campaign, 1812–1813, produced results that were beautiful but ultimately put into question the promise of the modern timeline. The visual simplicity of the diagram is paradigmatic as is the numbing pathos of its articulation across the space of the Russian winter. At the same time, through color, angle, and shape, Minard’s chart marks the centrality of the idea of reversal in the thinking and telling of history... The same could be said for the branching timeline in Charles Renouvier’s 1876 Uchronia (Utopia in History): An Apocryphal Sketch of the Development of European Civilization Not as It Was But as It Might Have Been, depicting both the actual course of history and the various alternative paths that might have been if other actions had been taken.

(Minard’s ‘Carte Figurative’ of the ‘successive loss of men’, via Wikipedia.)

Minard’s chart is a famous infographic—if I recall correctly, it gets a decent of airplay in Edward Tufte’s book on The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. I wasn’t aware of Charles Renouvier’s ‘Sketch’, which might be both an alternative history and even an early attempt to shape the idea of multiple possible futures (because if the past could be different...). The idea of ‘uchronia’ is a play on utopia: Not what was but what might have been.

It’s worth noting that the same edition of of Cabinet also has an infographic history of timelines that is well worth exploring.

Of course, by the time we get to the 20th century, time is being stretched in both directions: the very short and the very long. As Rosenberg says:

In 1945, it became relevant for the first time to tell world history in terms of milliseconds, and, very soon, it also became necessary to start thinking in practical terms about the transmission of information over the course of the very long term. There is something more than a little sobering about the recurrence of the cyclical form in the US government glyph for the declining radioactivity of nuclear waste stored in Yucca Mountain.

But that takes us into a different realm, and a different futures problem. How do you tell people 10,000 years away into the future—further from us in time than Ninevah and the Hanging Gardens of Babylon—that something is dangerous? It’s a reminder that all of this is culturally specific.

Notes from readers

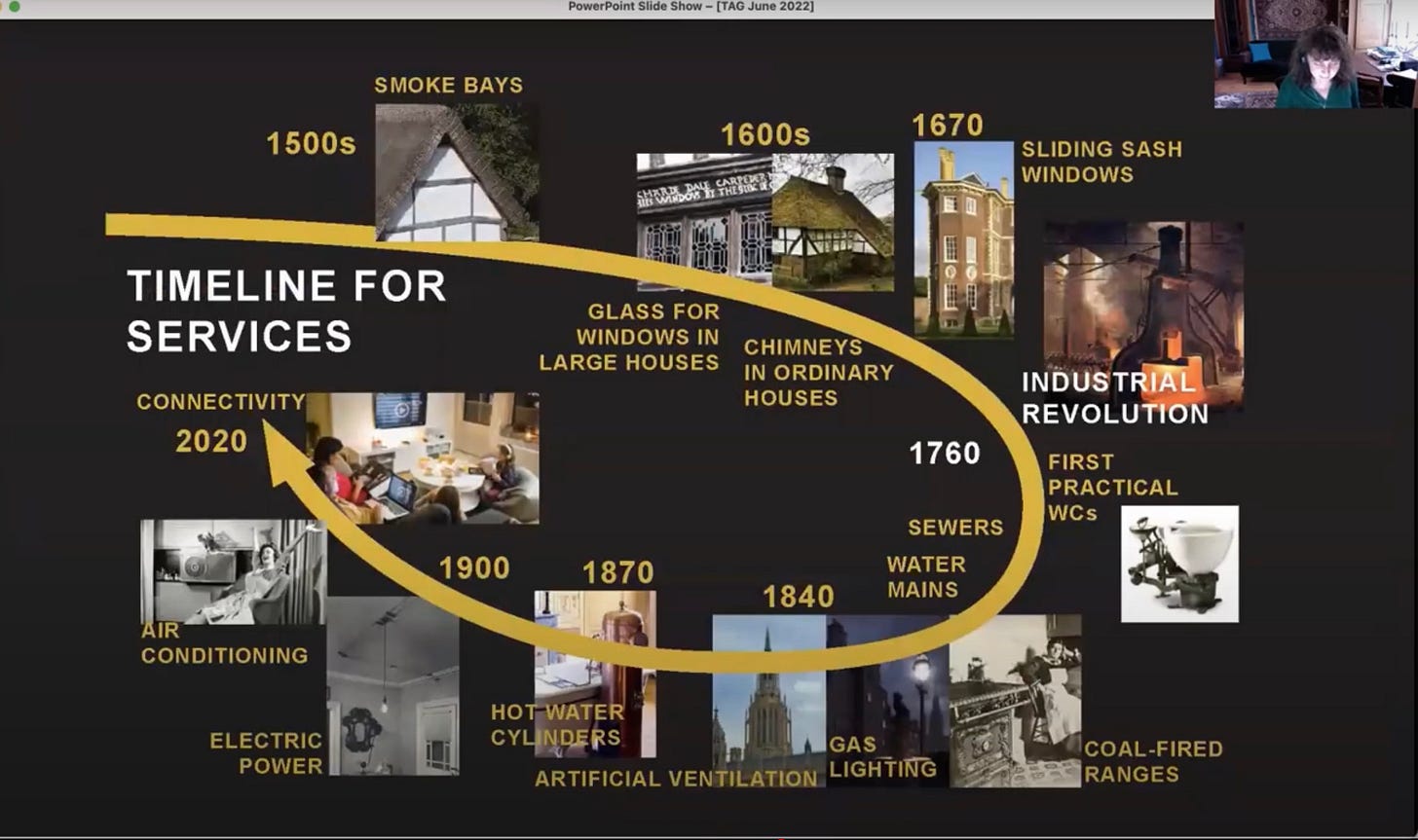

Robin Pender sent me a note after my piece on heat and cities about the way in which sash windows and the awning were introduced into building design as a response to solar gain as a result of domestic glazing, which came into British houses in the the 17th century. They disappeared again in the late 20th century, by which time we had forgotten what they were for. She sent me a link to a recent talk on how energy availability has influenced building form over the past few centuries, which inclueds a timeline of sorts:

Source: Robyn Pender)

Her email also reminded me that cities can influence developers and property owners to increase the amount of shade by making it a planning consent requirement for new buildings and renovations.

Also thanks to Simon Binhgam, who took the trouble to let me know that the environmental quarter being built on the site of Tegel Airport, which I wrote about yesterday, is named after the politician Kurt Schumacher, rather than EF or Michael - there is a Kurt Schumacher Platz alongside Tegel airport.

j2t#349

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.