22 December 2022. AI | Protest

Meaning, language, machines and being human. // The power of art and slogans

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Meaning, language, machines and being human

Heavens knows I’ve read a lot about ChatGPT recently. Everyone has an opinion about what writing generated by machine-learning large language models might mean for the future.

Some of this commentary has been excitable, but from the material I have seen the consensus so far is that if you give a large language model the internet to play with, and insert some rules on tone and style, the outcome is competent but bland. With the usual collection of concerns about what this might mean, say, for academics setting essays to students and so on.

So I was intrigued by Robert Cottrell’s attempt to do something a bit different with this “What about ChatGPT” genre. Cottrell is a former journalist and the founder of the Browser, and sends a letter to subscribers most weeks, often on what he’s been reading.

He had the intriguing idea of using a work by the modernist poet J.H. Prynne as the basis for his ChatGPT interaction:

For dent inflict yet amuse enamel will livid exceed

tactic nursing humid loss, nolore even alert at numb

unwind entry. Level ground pacific inversion has

wasted trapper, has few slicks. Run out portal upper

It comes from a book of Prynne’s called Streak—Willing—Entourage Artesian published in 2009. It consists of 72 quatrains similar to this one. And, well obviously, it makes no sense in terms of normal meaning and syntax.

John Clegg reviewed Streak for Poetry London, and makes this point:

Clearly, it’s unreadable in any conventional sense. There is no surprise, because the syntactic units are too small to provoke any expectation. Connections exist only between individual words... If we had a sense of the process by which this stuff is produced, we might know better what to do with it; but it is just this process which Prynne has withheld from us.

Cottrell asks if we’d respond differently to Prynne’s work if we thought it had been produced by a computer:

Even a piece of writing without any apparent literal meaning will appear to us somehow changed, foreshortened, stripped of its possibilities, if we are told it is the work of a machine and not of a person.

He doesn’t take this part of the argument much further than this, but it does seem to me that there’s a question in here somewhere about meaning. Prynne’s decision to remove conventional syntactical meaning from Streak is itself an act of meaning making.

Anyway, Cottrell, playing with ChatGPT, decides to ask the program to write in the style of J.H.Prynne, feeding it the quatrain above as a prompt. The program isn’t happy about this: not at all.

I'm sorry, but it seems that the text you provided does not make sense. Could you please provide more information or context about what you are trying to ask or discuss? I'll do my best to help with any questions or problems you have.

So he explained where it came from, and that he was having problems making sense of it: could the machine help?

It is difficult for me to accurately guess the meaning of the text you provided, as it is unclear and abstract, and does not seem to follow a traditional poetic structure or use familiar language. Without more context or information, it is challenging to discern a specific message or theme in the poem.

However, one possible interpretation of the text could be that it is describing a series of events or actions that are confusing or chaotic, and that involve some kind of physical or emotional injury or loss.

(There’s more here, and as a review of the quatrain it is, well, competent but dull.)

So Cottrell’s next question was to ask ChatGPT to continue the poem in the style of the original. And away went ChatGPT:

The darkness swirls, the void expands

A void of nothing, a void of all

The emptiness fills, the loneliness stands

The loneliness that greets, the loneliness that calls

By his account he tried to remind it

that Prynne's sample poem had neither rhyme nor meter, nor much recognisable syntax, and certainly no narrative. But still, each time, ChatGPT came back with an offering which resembled the lyric of a rock ballad much more closely than it did a modernist poem.

I had this down as late-Victorian lyric bombast rather than a rock ballad, but the point is the same. As Cottrell says:

Even this was, in its way, a perversely impressive performance. The machine was so well-trained that it simply could not bring itself to generate apparent nonsense.

(‘Three Machines’ (1963) by Wayne Thiebaud. Via rulenumberone2/flickr, CC BY 2.0)

Cottrell’s conclusion from this intriguing exercise is quite long and quite rich, and I am paraphrasing quite a lot here. The first:

we no longer need humans to produce conventional and mediocre verbiage. AI can now do that for us consistently and well. Pop-song lyrics and school essays are a solved problem.

And as he says, if ChatGPT can already write like he can,

then at some point it will be able to write like J.H. Prynne, or like Jane Austen, or like Thomas Pynchon. In some respects this should be a case for celebration: We can have endless new writing on tap, all perfectly done, as if by our favourite authors... If readers obstinately go on preferring new human authors to new AI authors, publishers can camouflage their machine-made products with human branding. The machines will be our new ghost-writers.

But there’s a longer and more complex point about the relationship between language and the idea of being human. Because to a significant extent, our knowledge of the world comes through books (and perhaps more broadly, texts). Machines can’t ‘know’ the world in any meaningful sense. But they can know the texts.

The real question, however, is surely a somewhat different one: Can machines plausibly represent how humans might think and feel? I believe they will be able to do just that, since they will be able to draw upon the totality of world literature and the totality of the humanities and the social sciences... I see no reason why a machine infinitely better-read than me should not serve up as fiction a version of the world which I find richer and more persuasive than my own.

There are some implications here as well. The training set of words will have, over time, a larger share of AI-generated text to draw on. The process, in other words, will become recursive:

Human-made language will reduce to smaller and smaller percentages of any training corpus, especially if the corpus is weighted for recency. Instead of maintaining a language that machines can use, humans will become users of a language that machines will maintain.

And that leads to a further thought: that humans have elevated the importance of language perhaps because they have thought that it distinguishes us as a species. But if machines can pick it by crunching datasets, perhaps we have over-rated its importance:

Our instinct is to raise the status of the machines ("they are like us!") whereas what we should be doing is lowering the status of language.

In which case, why stop at human language? Why not the language of other species as well?

the machines would be able to interpret between humans and other animals, allowing for conversations that humans throughout their history have not merely never troubled to attempt, but have actively shunned, on the grounds that animals, being animals, could not possess language as such.

2: The power of art and slogans

(Harriet Richardson, Never Look Directly at The Sun © Harriet Richardson, 2022)

There’s a nice piece at It’s Nice That on the work of the designer Harriet Richardson. She became a ‘political’ designer slightly by accident, after getting 15 seconds of online fame at the 2019 Youth Climate strike. She had quickly knocked up a poster that said, “Leonardo DiCaprio’s Girlfriends Deserve a Future”—referencing DiCaprio’s penchant for girlfriends under 25. A clip went viral on Twitter, amassing 2.5 million views, and interviews in more conventional media followed:

But instead of simply providing Harriet with a sweet moment of internet stardom, the event also made Harriet aware of the power that simple, well-executed design could have. “The real time mass-acknowledgement of a piece of design that I’d created was incomparable to anything I’d felt before. Added to this, the fact that the motivation behind it was for a greater good was truly a wonderful feeling,” she reflects. “I remember thinking: ‘I wish I could do this all the time.’ And then realised the only thing stopping me was the belief that I couldn’t.”

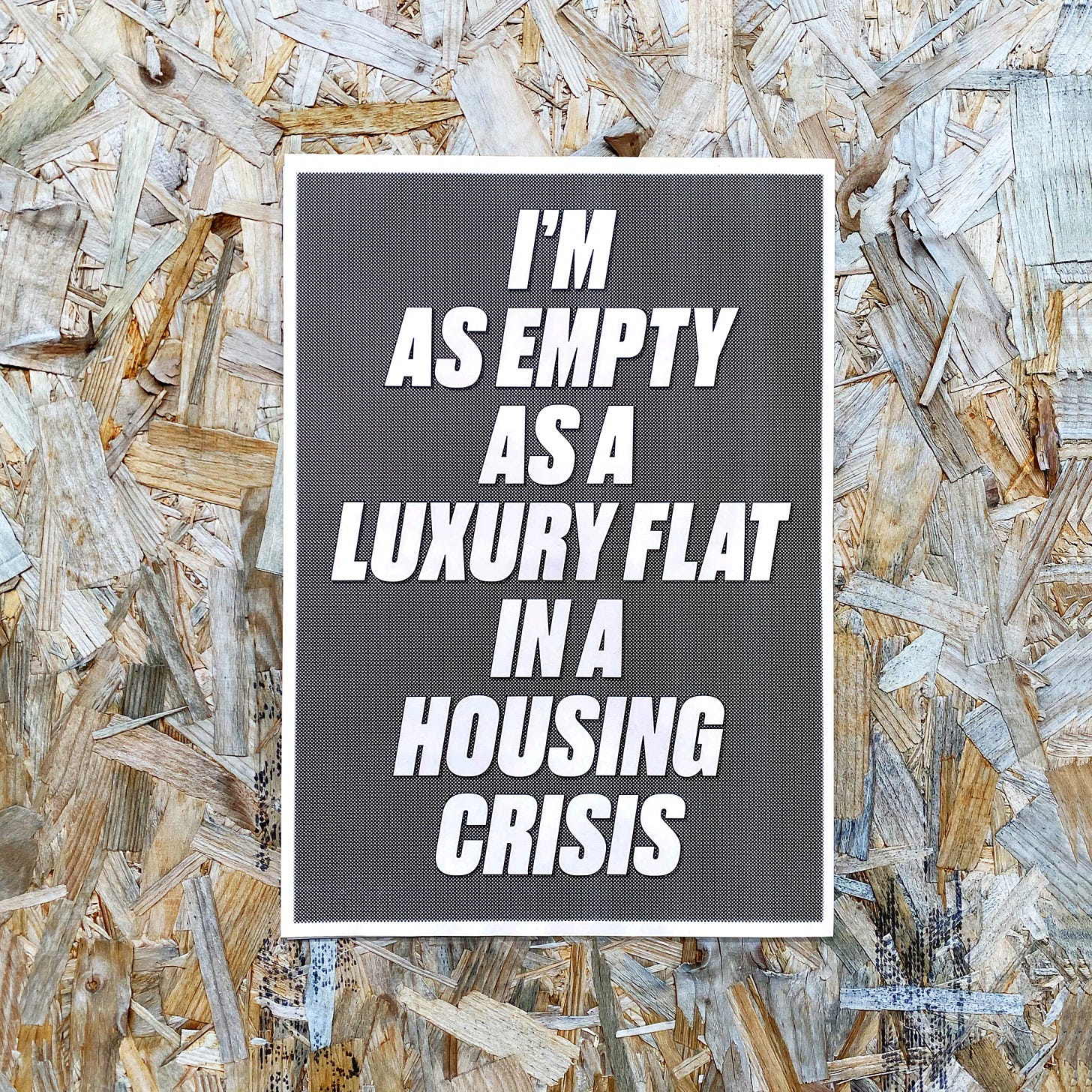

Her current work sits somewhere between graphic design and art, using a wide range of media, although she’s a fan of the punchy slogan. She says that 20 years ago she’d probably be knocking out copy lines for razors, but these days she can choose not to work with companies that don’t align with her ethics and values:

Actively choosing to not take work from companies that don’t align with her ethics is also something that has come with Harriet’s career progression. “You would think the hardest part of my development as a designer would be turning away well-paid work for big capitalistic corporations, but it feels fucking great,” she laughs. “Once you start turning down immoral work, you’ll never look back.”

(Harriet Richardson: Fragile Girlie © Harriet Richardson, 2022)

Her current work is looking at mental health, and sex and violence. She has been touring universities with a talk called ‘Why I Am Having a Nervous Breakdown and How You Can Benefit’, which seems to be linked to her work Fragile Girlie.

which Harriet explains errs much more to the art side of her work, using fragile box tape to realise its message. “This was inspired by a much-needed breakdown I had following the cancer diagnosis of my mother,” she says. “It’s also been the inspiration behind a body of work named Femme Fatality, which I am currently working on.”

Femme Fatality is scheduled for an exhibition at the Barbican in London next year.

(Harriet Richardson: Luxury Flat © Harriet Richardson, 2022)

j2t#409

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.