21 June 2022. Work | Noise

Amazon is running out of workers. // It’s loud out there in the city.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. And a reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. There wasn’t a Just Two Things yesterday.

1: Amazon is running out of workers. It can blame itself

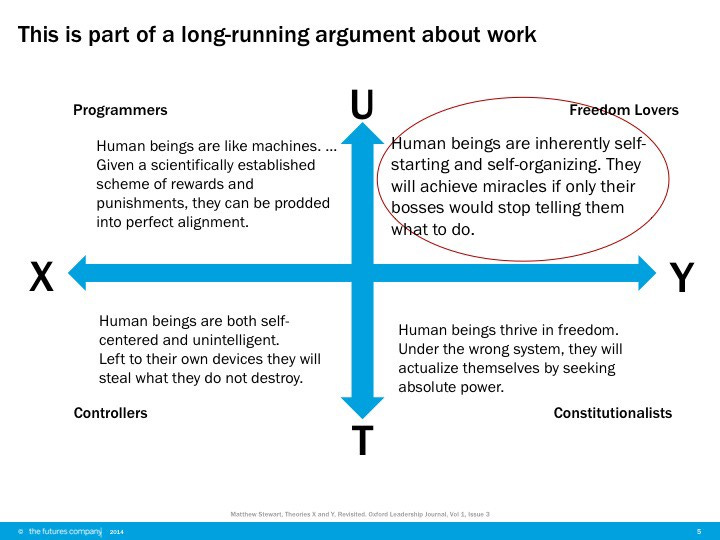

A few years ago I wrote a report for the Association of Finnish Work in which I explored the trends around work, exemplified by a 2x2 that Matthew Stewart had developed based on Douglas McGregor’s work on Theory X and Theory Y. There’s a longer article about that work on my Medium page.

In Theory X, paraphrasing quite a lot, people don’t want to have to work, and have to be coaxed into it. Management is all sticks. On Theory Y, people want to work, especially if they get some scope for self-management. The job of management isn’t carrots, but more precisely to put some guardrails in and then get out of the way.

To this, Matthew Stewart had added an axis about conflict, running from‘T’ to‘U’. ‘Tragic’ represents a worldview in which conflict is inevitable and not resolvable; ‘Utopian’ a world in which conflict stems from misunderstandings that can be resolved. We can park any misgivings about these labels for the moment, but the 2x2 looks like this:

(Source: Matthew Stewart/ Douglas McGregor)

As can be seem from the helpful circle, my personal view is that business in general is heading in the direction of the top left, and not just in areas of knowledge work. Both the social care business Buurtzorg and the materials company A.L. Gore (makers of Gore-Tex) tend in this direction, for example.

And every time I presented this diagram, someone in the audience would put their hand up and say, ‘Yeah, but what about Amazon?’. Because Amazon is definitely sitting down there in the bottom left ‘Controllers’ quadrant.

And this was a pretty compelling argument. Amazon employs even more people now than it did then, and was growing. So I typically ended up saying instead that this was a battle between management types, and we’d see how things turned out. I’d usually mention that Zappo’s, owned by Amazon was also in the top right quadrant. There was nothing inevitable about selling things online and being a Controller.

Well, it turns out that systems continue only until they stop continuing. Their reinforcing loop sooner or later runs out of steam as it hits the buffers of a balancing loop.

At least, that’s the conclusion I reach from an article in Vox’s Recode section that reports on an internal memo from mid-2021 that Amazon is running out of workers.

Amazon is facing a looming crisis: It could run out of people to hire in its US warehouses by 2024, according to leaked Amazon internal research from mid-2021 that Recode reviewed. ... “If we continue business as usual, Amazon will deplete the available labor supply in the US network by 2024,” the research, which hasn’t previously been reported, says. ... The leaked internal findings also serve as a cautionary tale for other employers who seek to emulate the Amazon Way of management , which emphasizes worker productivity over just about everything else and churns through the equivalent of its entire front-line workforce year after year.

Amazon has a labour recruitment model that looks at the available labour pool of the type of people who’d be likely to work in an Amazon warehouse in each area where it operates, by qualifications, wages, and so on. The trouble is that Amazon’s labour model is so punishing that it its turnover rates are ludicrously high. The Recode article reports that turnover was 123% in 2019, and hit 159% in 2020. In other words, in 2020 it replaced the equivalent of its labour force in less than eight months.

Comparable rate for the US transport sector in 2020 are 46%, 59% for warehousing, and 70% for the retail sector. A relatively mild decline in labour force turnover would push Amazon’s labour crunch back a couple of years.

So although some of Amazon’s issues are down to the fact that people do turn to warehouse work when other things fail for them, most of them are down to Amazon’s management choices:

In a company survey of 31,000 workers who left Amazon that was referenced in the report, some former Amazon workers say it’s worse to work at Amazon than some big-name competitors like Walmart or FedEx. In that survey, those who joined another employer soon after leaving the tech giant “rated Amazon significantly worse on work fitting skills or interests, demands of the work, shift length and shift schedule.”

Competitors like Walmart are currently paying more for warehouse staff with less of Amazon’s abrasiveness. In geographical areas like California’s ‘Inland Empire’, a big logistics hub near Los Angeles, people can more or less just walk across the road and be re-hired by a competitor.

The memo anticipates that Amazon will be out of its labour pool in Phoenix by the end of 2021, and in Inland Empire by mid 2022. The Phoenix warehouse hit 205% labour turnover in 2020–the entire workforce, or its equivalent, in less than six months. So, given this, we can test what’s happened, since the Phoenix warehouse is still operating.

Amazon seemed to have reversed, or stopped enforcing, some workplace policies at Phoenix warehouses amid the labor shortage, according to a former manager.

“They were so concerned about attrition and losing people that they rolled back all the policies that us as managers had to enforce,” Michael Garrigan, a former entry-level manager at Amazon warehouses in Phoenix from 2020 to early 2022, told Recode. “There was a joke among the … managers that it didn’t matter what (workers) got written up for because we knew HR was gonna exempt it. It was almost impossible to get fired as a worker.”

This is the place where I need to say that Amazon “didn’t refute the contents of the memo”, but declined to comment either on its contents or on Michael Garrigan’s claims about Phoenix’s HR operations.

(Amazon warehouse in Maryland during an official visit by the Governor. MarylandGovPics/flickr, CC BY 2.0.)

Of course, historically, Amazon has used turnover as both a management policy, to deal with peaks and troughs, and a way of enforcing discipline, as we have seen in its recurring fights over unionisation. Right now, because they are over-staffed in some parts of the country (a COVID-19 staffing effect) they are likely to use attrition to reduce numbers in those areas. But this isn’t a long-term business strategy.

There are ways to at least delay these problems. Higher wages help to keep staff, as would removing aggressive HR policies such as automatic termination. (There’s a telling story in the article about a worker being automatically terminated because he took longer than advised to sort out an abscess on a tooth, but couldn’t use his vacation time to sort the problem out, because vacation needs to be applied for in advance.)

Less aggressive applicant screening would improve recruitment numbers; increased automation would reduce labour demand, but wouldn’t help reduce Amazon’s injury and safety issues unless the tightly monitored Taylorist work regimes also changed.

Ironically, some of the benefits that would come with union recognition—better wages and conditions, less arbitrary management, even a little bit of respect for the workforce—would reduce turnover and give Amazon a bit more labour slack. The chances of the allegedly rationally run Amazon business looking at the available data and coming to this conclusion? Less than zero.

2: It’s loud out there in the city

We’ve known for almost two decades now that noise is a killer. Successive reports from the World Health Organisation have pointed this out. here’s a summary from their 2010 Factsheet:

Noise is an underestimated threat that can cause a number of short- and long-term health problems, such as for example sleep disturbance, cardiovascular effects, poorer work and school performance, hearing impairment, etc.

And it also described the incidence of noise issues:

According to a European Union (EU) publication:

- about 40% of the population in EU countries is exposed to road traffic noise at levels exceeding 55 db(A);

- 20% is exposed to levels exceeding 65 dB(A) during the daytime; and

- more than 30% is exposed to levels exceeding 55 dB(A) at night.

But unless urban noise vanishes, as it did for a glorious period during the first lockdown in 2020, it’s hard to remember how much noise there is out there in cities, and how bad it is for us. (The brain is quite good at screening noise out, even while it’s being stressed by it). So we should be grateful that Possible has put together noise maps for London, Paris and New York.

(London noise map. Source: Possible)

Inevitable, the biggest noise corridors are to do with roads, or others transport. The big ugly red triangle to the west on the London map is Heathrow Airport. London does seem quieter than Paris, perhaps because it’s more spread out.

(Paris noise map. Source: Possible)

The maps are interactive, in that you can mark them for somewhere you live or work and get the specific noise reading highlighted.

As Possible reminds us, decibels are not a linear scale, but a logarithmic one. Every increase of 10 decibels represents a doubling of the ambient noise levels: 80 decibels is four times as loud as 60 decibels.

There’s also a class gradient: poorer people are likely to live, and work, and go to school in noisier places.

Which is probably a good place to mention that a study of the effects of noise on pupils at 38 primary schools in Barcelona found that pupils who were exposed to more noise experienced slower cognitive development. It is just published, although the fieldwork was done between 2012 and 2013. The researchers assessed the impact on attention and working memory:

(T)he findings showed that the progression of working memory, complex working memory and attention was slower in students attending schools with higher levels of traffic noise. By way of example, a 5 dB increase in outdoor noise levels resulted in working memory development that was 11.4% slower than average and complex working memory development that was 23.5% slower than average.

Poorer student performance was associated with both higher average noise levels, and greater fluctuation in noise levels. School noise levels seemed to be the critical factor. Noise levels at the pupils’ home location seemed to have no effect on cognitive development, but this may be because these were estimated for the study, rather than being measured. And fluctuations seemed to have a big effect, which matters for policy, since at the moment policy focusses on average noise levels, not peaks.

Updates

While looking for the piece about the future of work, quoted in the Amazon piece above, I also stumbled across a blog post I’d written in the immediate aftermath of the Grenfell Tower fire, describing it as an example of ‘slow violence’. (I wrote about Grenfell last week). The concept of slow violence was developed by Rob Nixon as a way to understand environmental disasters, and was explained by Subhankar Banerjee in the Los Angeles Review of Books like this:

Slow violence, however, as Nixon points out, occurs “out of sight.” He also works with two concepts of time: strictly temporal (slow or fast) and aesthetic (spectacular or unspectacular). Slow violence occurs, needless to say, “gradually”; the “insidious workings of slow violence derive largely from the unequal attention given to spectacular and unspectacular time.”

j2t#333

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.