20 October 2021. Political economy | Power

Goodbye Washington Consensus, hello Cornwall Consensus; the four approaches to organisational power.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. (For the next few weeks this might be four days a week while I do a course: we’ll see how it goes). Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: Goodbye Washington Consensus, hello Cornwall Consensus?

The UK-based, Italian-born academic Mariana Mazzucato is having one of those moments that academics rarely see: her ideas about innovation translated into policy. Her books on The Entrepreneurial State and The Mission Economy, with one or two others in between, have challenged the way that states—notably within the EU—think about public innovation.

The idea of public-private ‘missions” is that the state needs to use its capacity to shape the economy at a scale that’s appropriate to the scale of the challenges that we now face. The state, in other words, is an actor in the economy rather than being some kind of combination of referee and groundskeeper. That doesn’t mean that the private sector has no role. But when it comes to mobilising capital, the state can do it better than the private sector can.

This represents—her phrase in an article in Social Europe—the ‘Cornwall Consensus, which emerged from the recent G7 meeting in St Ives, chosen to contrast with the ‘Washington Consensus’, which has dominated the international discourse about economics and the role of the state for several decades:

Whereas the Washington Consensus minimised the state’s role in the economy and pushed an aggressive, ‘free-market’ agenda of deregulation, privatisation and trade liberalisation, the Cornwall Consensus (reflecting commitments voiced at the G7 summit in Cornwall last June) would invert these imperatives. By revitalising the state’s economic role, it would allow us to pursue social goals, build international solidarity and reform global governance in the interest of the common good.

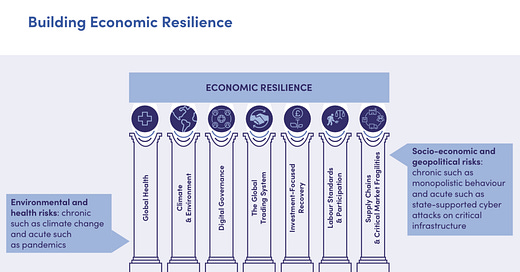

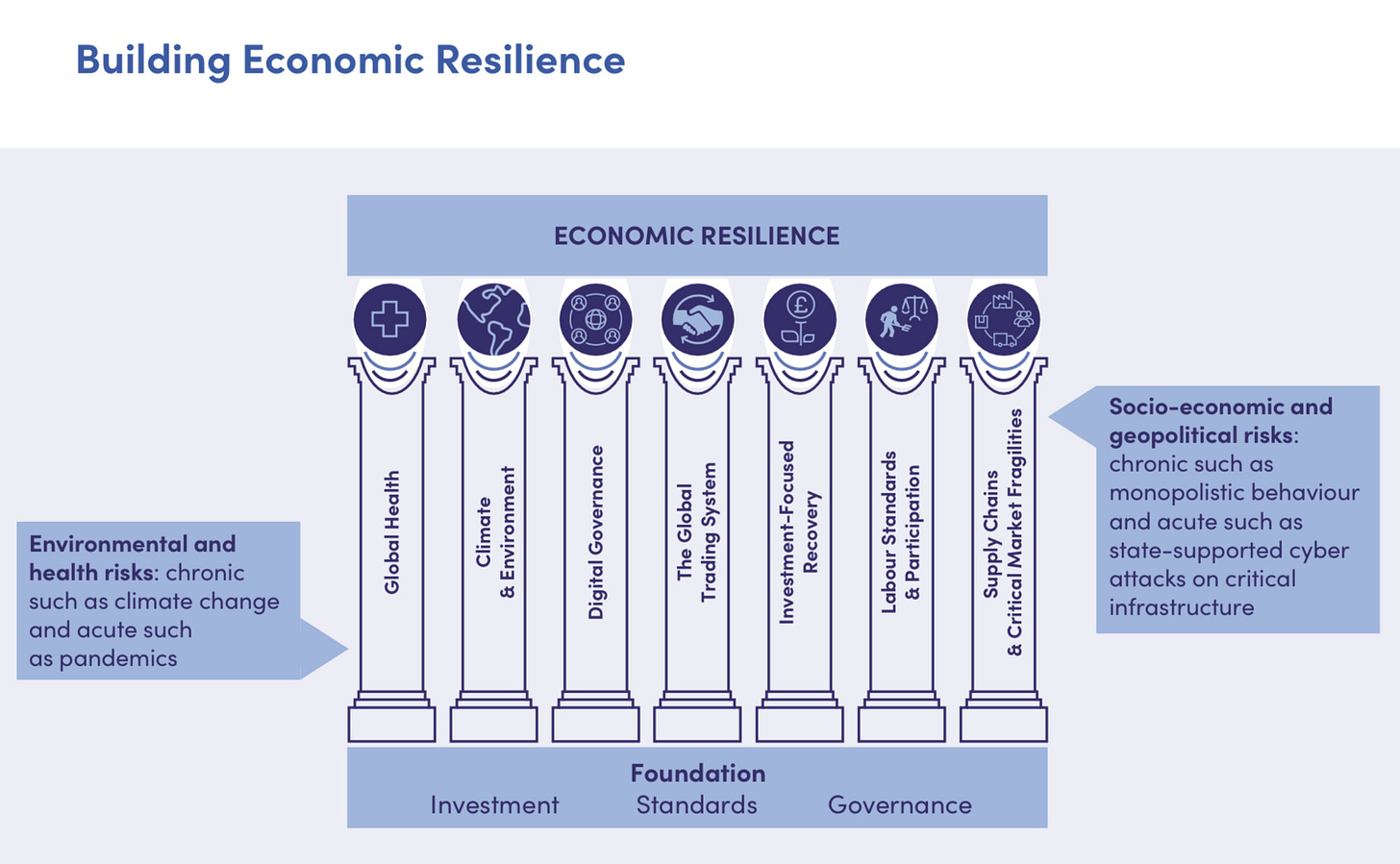

(Source: the G7 Panel on Economic Resilence)

Part of her evidence that we may be seeing such a transition is that the G7 Panel on Economic Resilience, on which Mazzucato sits, has just released a report promoting the ‘Cornwall Consensus’. The Panel reports directly to G7 leaders, and so has some influence. Here’s a flavour from the Executive Summary:

There are three big themes – investment, standards and governance – which we bring together in proposals to tackle market failures in critical minerals, semiconductors and digital/data - the oil, steel and electricity of the 21st Century economy.

The underlying idea of mission driven economies is that we need to reconsider the relationship between the state and markets. Of course this perspective has its critics. The economist John Kay, no great fan of markets, thinks it invites the state to develop missions where there is ambition and scale, but little sense.

In contrast, a review of her book at the LSE blog thinks that state-driven missions may not be enough to deal with a levels of dysfunctional capitalism we see.

This is Mazzucato’s version of this, in her Social Europe article:

The Cornwall Consensus would also have us move from reactively fixing market failures to proactively shaping and making the kinds of markets we need to nurture in a green economy. It would have us replace redistribution with pre-distribution. The state would co-ordinate mission-oriented public-private partnerships, aimed at creating a resilient, sustainable and equitable economy.

In truth, we’ll get some clues as to whether she is right at the end of this month, when the G20 nations meet in Rome to discuss ‘how to overcome the great challenges of today’, potentially informed by the Economic Resilience report. We clearly need our economies to move faster, and at greater scale, towards the carbon transition, and markets won’t do that on their own.

From a futures perspective, the timing of all of this is interesting. The political scientist David Runciman once noted that—at least in the UK—there had been a pattern of financial crisis about every 40 years, going back a century or so, with a restructuring of political systems about a decade later (1906–1945–early 80s). We also see 40- and 80-year cycles in the Strauss and Howe work on the ‘Fourth Turning), although it’s not clear why. (Generations are a bit longer than 20 years these days; it might be a function of career length).

All the same, the sceptic in me worries that old systems take a long time to die, even when they are producing outcomes that are bad for almost everyone. This is especially true when so many politicians and officials have done so well personally from the old model. The UK Chancellor’s austerity-oriented response to the public debt created by the pandemic is a case in point. Almost everything we’ve learned about austerity in the last decade says this is a mistake, but he advocates it and Treasury officials do it anyway.

#2: The four approaches to organisational power

There’s an interesting article in Strategy+Business discussing a new book, Power for All, by Julie Battilana and Tiziana Casciaro which offers a model of the sources of power in the contemporary organisation.

I’m short of time, so this note will be little more than a list. The authors—academics at Harvard and the Rotman Institute respectively—seem to have breathed some new life into the idea of power dependence theory, first developed by Richard Emerson.

As Battilana and Casciaro tell it, it’s not your personal or positional power that determines your effectiveness in any given situation. It is your ability to understand what resources the involved parties want and how the resources are distributed—that is, the balance of power. “We find this extremely compelling,” explains Casciaro, “because it brings power relationships—whether they are interpersonal, intergroup, interorganizational, or international—down to four simple factors.”

From this ‘power as access to resources’ perspective, they argue that there are basically four strategies to gain and manage power.

- “If you have resources the other party values, attraction is a key strategy. You try to increase the value of those resources for the other party. “

- “If the other party has too many paths to access your resources, consolidation is a key strategy. You try to eliminate or otherwise lessen the alternatives.”

- “If the other party has resources you want, withdrawal is a key strategy. You try to reduce your need for the resources.”

- “If you don’t have enough alternatives to the other party’s resources, expansion is a key strategy. You try to find outside options.”

Some quick examples of these: attraction might lead you to build networks, so increasing the perceived value of your resources. Consolidation sits behind a lot of corporate M&A. Withdrawal, in the business context, might be about automating processes so as to reduce dependence on labour. Expansion sits behind outsourcing and offshoring of production.

Of course, one of the catches is that you do need to understand what the other party values. And that requires empathy—something that those close to power don’t always have.

j2t#191

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.