2 April 2024. Chocolate | Economics

The chocolate crisis // What’s wrong with mainstream economics [#556]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: The chocolate crisis

One of the warm-up exercises I sometimes use in futures exercises is to think of a food they like that they think will be a lot more, or a lot less, available in 20 years time. Chocolate usually appears on the list as you go round the room.

But looking at the recent spike in world chocolate price, it looks as if chocolate may be a lot less accessible a lot sooner than that. Hannah Ritchie has just published a useful guide on her newsletter on what’s happening. Sadly, it doesn’t seem likely to improve the incomes of West African cocoa farmers, or not in the short term.

(Source: Bloomberg)

Of course, when you see a market price chart that looks like that, the first thought is “speculators”, and that is inevitably part of the story here. But the beginning of the increase in price was caused by a combination of increasing demand and tightening supply; climate change has something to do with the supply issues.

Two thirds of the world’s cocoa comes from West Africa—in fact almost all of that comes from Cote d’Ivoire, the world’s largest producer by a distance, and Ghana. (A bit less than a sixth comes from Latin America and Asia respectively. Indonesia is the largest producer in Asia and Brazil, Ecuador and Peru are the leaders in Latin America).

In West Africa, cocoa production has been affected by El Nino, but more seriously extreme rainfall has meant the crop has been hit by two different viruses:

West Africa experienced extreme wet conditions late last year, driving an outbreak of “Black pod disease”. This is a fungal disease which tends to spike just after the wet season. If it’s not treated, it can destroy an entire harvest... This extreme rain was followed by extremely dry conditions, which has helped the spread of another disease: the “Swollen shoot virus”. This disease only occurs in West Africa and is spread by insects called “mealybugs”.

The second one of these—which Ghana has been trying to eradicate for a hundred years now—leads to a 25% decline in output in the first year, and 50% in the second year, and seems currently to have no fungicide-based solution. There are some fungicides that can address the first problem, but farmers don’t always have access to them, or can’t afford them.

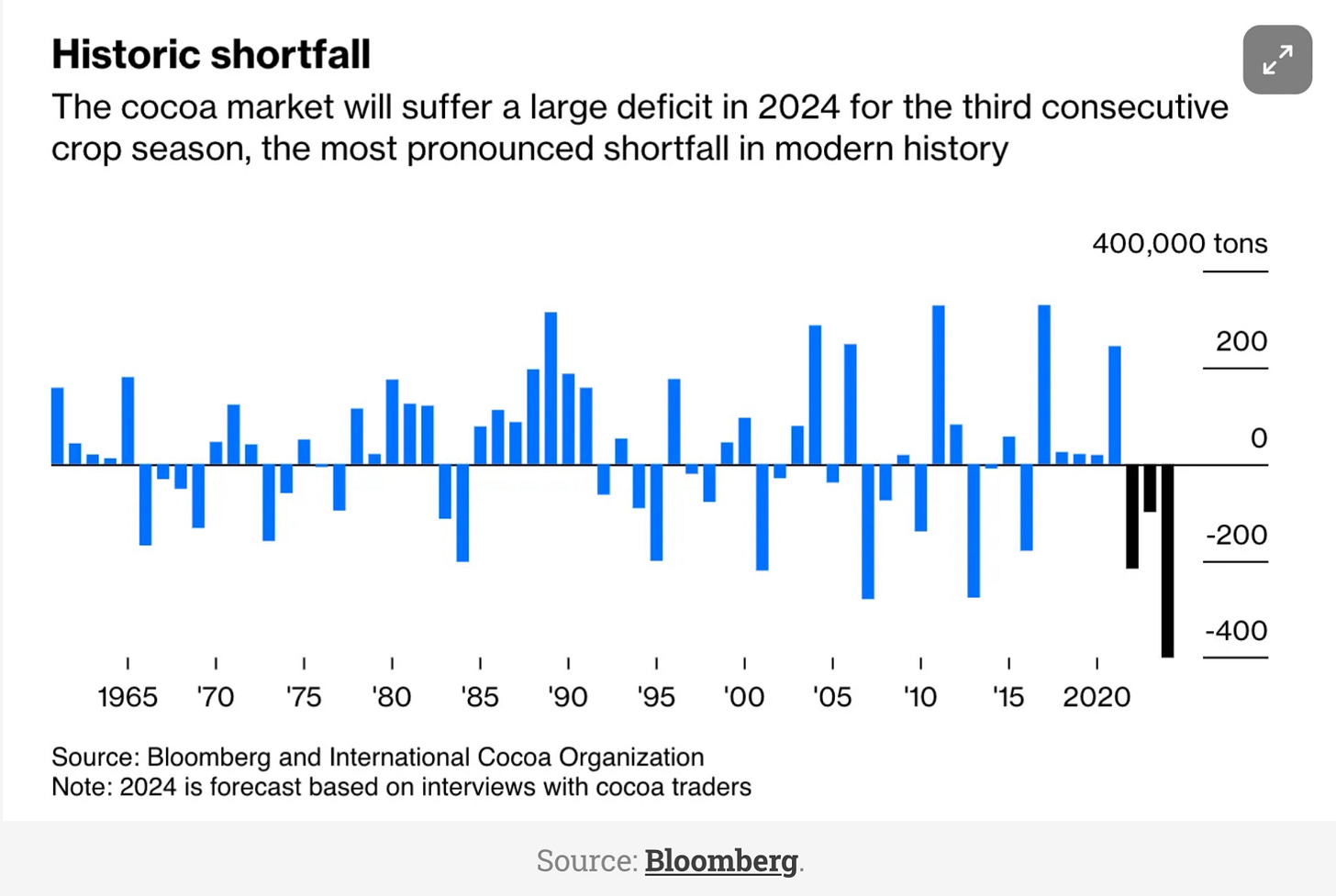

In a normal year, world global production is around six million tonnes. The International Cocoa Organization is projecting a half million tonne shortfall this year, and that’s on the back of shortfalls in both the previous years, as another Bloomberg chart shows.

(Source: Bloomberg)

One of the issues that Hannah Ritchie doesn’t mention here but was picked up in an Financial Times Long Read (likely paywalled) is that global chocolate demand is also rising, and that the big producers are short on cocoa stocks, so they’re also pushing up prices as they scramble to secure supplies. This is from the FT:

Demand for cocoa has doubled in recent decades, creating a massive shortfall. According to the International Cocoa Organization’s forecasts demand is set to outstrip supply by more than 370,000 tonnes this year. Deficits are only material if they move the stock to consumption ratio — the amount of stock in the world versus the total consumption — “and is it bloody moving it,” says Nicko Debenham, managing director of Sustainability Solutions, which advises companies.

Margins at the big chocolate manufacturers have been squeezed, and there have been layoffs. They may only have themselves to blame, of course. With a few honourable exceptions, mostly they have been happy to take the low prices the market offered and were uninterested in where it came from. One of the observations I’ve discussed on Just Two Things before is that in a climate change world, “security” extends to food security.

If you’re a chocolate manufacturer and you’re not investing in your primary producers in a way that also keeps them in business, in a climate change world you’re likely not to be in the chocolate-making business for much longer. Mostly the only companies who understand this are those who have an ethical approach to their businesses, such as Chocolonely.

(Cacoa pods. Photo: USDA Agricultural Research Service. Public domain.)

One of the problems of the cocoa market, especially in West Africa, is that the producers have been impoverished for a long time. Many live below the international poverty line, and do not make enough for a “living income”. This makes it impossible for them to invest in their farms.

As a result, in Ghana, farmers will rent their land to illegal gold miners, who pay them more than they make from cocoa. Cocoa production has also been a source of deforestation in west Africa, and this is a looming regulatory problem, because the EU—its biggest market—is about to introduce regulations banning the import of coca beans grown on recently deforested land.

In recent years, the two west African governments have developed a cartel that has put a floor price underneath the market, designed to give farmers a living income. It’s based on a premium against the cocoa futures price. However, it’s set against last year’s prices, so west African cocoa farmers there won’t see an increase in prices until next year. (This isn’t the case in Latin America, where farmers’ incomes have increased).

According to Susannah Savage in the FT:

Alex Assanvo, one of the premium’s architects, who heads the initiative that oversees the Ivory Coast and Ghana cocoa alliance, says that today’s supply crunch is the legacy of unfairly low prices, proving that “we were totally right to build a system that would protect farmers and farmgate prices from this current speculative market.”

The way Hannah Ritchie summarises the issues here is as follows:

The world’s cocoa is produced is a small number of countries that are highly vulnerable to climate change and other threats;

The farmers haven’t been paid enough historically to invest in crop protection or crop management;

Diversifying the crop into more countries might help, and this might happen with higher prices;

But if we’re serious about sustaining cocoa production, the farmers need to be paid more.

This is likely to might mean that Western consumers have to pay more for their chocolate. Already, the manufacturers are reducing bar sizes. But the way to make that a sustainable business is to turn chocolate into a premium product that is more of an occasion, rather than an impulse buy on the way past the checkouts.

2: What’s wrong with mainstream economics

There’s a short article by the economist Angus Deaton on ‘Rethinking My Economics’ at the IMF’s website, in which he discusses what’s wrong with the way economics thinks about the world.

It’s part of a section that the IMF included in a recent edition of its magazine (pdf) Finance & Development, and as well as Deaton, the other contributors to the section include Jayati Ghosh, Diane Coyle, Atif Mian, John H. Cochrane, and Michael Kremer.

(Angus Deaton in 2015. Photo: Bengt Nyman via Wikipedia. CC BY-SA 4.0)

Deaton is best known for his work with Anne Case (who’s also his wife) on America’s ‘deaths of despair’, and he in his late 70s now, so he has a perspective on that period when neoclassical economics became the dominant way of understanding the world, especially the policy-making world.

After the briefest of nods to some of the things that economics might have been useful for in that period, his starting point is that the profession is “in some disarray”. For example:

We did not collectively predict the financial crisis and, worse still, we may have contributed to it through an overenthusiastic belief in the efficacy of markets, especially financial markets whose structure and implications we understood less well than we thought.

And so, as he says in the article, he has in recent years found himself “changing my mind”. You have to have some respect for someone who is willing to do this after 50 years immersed in the metier of a particular discipline.

Helpfully he lists out the factors he is changing his mind about, so I’ll just abbreviate them a bit here. I’ve added the numbers to his headings. He’s also clear that he’s talking about mainstream economics, while being aware that there are many non-mainstream economists out there.

1. Power

Our emphasis on the virtues of free, competitive markets and exogenous technical change can distract us from the importance of power in setting prices and wages, in choosing the direction of technical change, and in influencing politics to change the rules of the game. Without an analysis of power, it is hard to understand inequality or much else in modern capitalism.

2. Philosophy and ethics

...(W)e have largely stopped thinking about ethics and about what constitutes human well-being. We are technocrats who focus on efficiency. We get little training about the ends of economics, on the meaning of well-being—welfare economics has long since vanished from the curriculum—or on what philosophers say about equality.

3. Efficiency

He thinks that economists have over-rated the value of efficiency, possibly by paying too much attention to Lionel Robbins’ definition of economics as “the allocation of scarce resources among competing ends”. Versions of this suggest that

economists should focus on efficiency and leave equity to others, to politicians or administrators. But the others regularly fail to materialize, so that when efficiency comes with upward redistribution... our recommendations become little more than a license for plunder... (S)ocial justice can be an afterthought.

4. Empirical methods

He reviews in a line or so the reasons why empirical methods have such sway—basically a reaction to what he drily describes as “the identification of causal mechanisms by assertion”. But this has created a vast blindspot, with too much attention on “local effects”,

and away from potentially important but slow-acting mechanisms that operate with long and variable lags. Historians, who understand about contingency and about multiple and multidirectional causality, often do a better job than economists of identifying important mechanisms that are plausible, interesting, and worth thinking about.

5. Humility

We are often too sure that we are right. Economics has powerful tools that can provide clear-cut answers, but that require assumptions that are not valid under all circumstances.

The second part of the article, headlined ‘Second Thoughts’ includes some areas where he thinks the world has changed since when he first learned his economics, or perhaps where economics has over-stated the way it thinks the world works.

One of these is trades unions. He acknowledges that (as with many in his cohort) he regarded unions as institutions that interfered with economic efficiency. But since then, corporations have become far more powerful—actually he says “corporations have too much power over working conditions, wages, and decisions in Washington”:

Unions once raised wages for members and nonmembers, they were an important part of social capital in many places, and they brought political power to working people in the workplace and in local, state, and federal governments. Their decline is contributing to the falling wage share, to the widening gap between executives and workers, to community destruction, and to rising populism.

Having been brought up in a family that believed that unions were useful social institutions, almost all of the things he says about unions now were true in the ‘60s and ‘70s, when he learned his economics: they raised wages for members, they were an important of social capital, and they were a source of political influence for working people. I’m not sure why it should take 40 years of neoliberalism to notice these things, unless it’s because you don’t know what you’ve got until it’s gone.

He’s mostly writing about the US, and he’s also sceptical of “the benefits of free trade to American workers.” He’s also no longer sure that “globalisation was responsible for the vast reduction in global poverty over the past 30 years, which seems quite a big step to me. (His emphasis).

I believe that the reduction in poverty in India had little to do with world trade. And poverty reduction in China could have happened with less damage to workers in rich countries if Chinese policies caused it to save less of its national income, allowing more of its manufacturing growth to be absorbed at home.

For him, this has also raised ethical questions about responsibilities to different workers in different locations:

I had also seriously underthought my ethical judgments about trade-offs between domestic and foreign workers. We certainly have a duty to aid those in distress, but we have additional obligations to our fellow citizens that we do not have to others.

Finally, he also has a view on the economic effects of immigration that goes against the mainstream. The prevailing view is that migration has little-to-no-cost to domestic workers, and great benefit to the migrants.

Picking up on his note above on the value of longer-term perspectives, he says that a longer view suggests a different story, at least in the US:

Inequality was high when America was open, was much lower when the borders were closed, and rose again post Hart-Celler (the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965) as the fraction of foreign-born people rose back to its levels in the Gilded Age.

I’m assuming that when he says “the borders were closed”, he’s referring to the immigration controls imposed in 1924. I’m wondering about the relationship between correlation and causality here—because I suspect that inequality has more to do with power.

But it’s possible that tighter controls on migration gave trades unions more leverage over US labour markets, which they were able to use effectively during the years of the New Deal. Immigrants also bring economic and cultural innovation with them. I suspect this needs more research.

j2t#556

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.