19 July 2022. Heat | Time

Cities aren’t prepared for heat. // The invention of the ‘time line’.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter.

1: Cities aren’t built for heat

With perfect timing, the Bulletin of the Atomic scientists has launched a series on whether we are ready for the world of heat that is coming our way. (I’m writing this in the UK, which has seen its first ever ‘Red’ warning for heat, and where temperatures may touch 40 degrees today, against for the first time ever.

But obviously this is not just a local concern. This is the context setter from Jessica McKenzie’s introduction:

The United Kingdom will be one of the hottest places on earth today, reaching temperatures more commonly seen in the Western Sahara and the Caribbean. Temperatures in Portugal and Spain soared to triple digits last week as wildfires ripped through both countries. The heat wave that has engulfed Western Europe could last for weeks; meteorologists say it could be the worst Europe has seen since 1757.

China, too, issued alerts to residents of nearly 70 cities as temperatures rose to 104 degrees Fahrenheit last week. According to a state news agency, Shanghai has only experienced temperatures greater than 104 degrees Fahrenheit on 15 days since 1873.... Earlier this month, at least 10 cities in Arkansas, Colorado, Oklahoma, and Texas broke high-temperature records, some by as much as six degrees Fahrenheit.

It’s an American article, so all the temperatures are in Fahrenheit, but 104 degrees F is 40 degrees C.

The first article in the series is about whether cities are designed for the heat. Of course, they’re not.

The problem with heat is that it kills, but it kills quietly. Heat related deaths are up everywhere, as John Morales notes in his article on cities:

Heat-related deaths are up across all continents over the last three decades. Since 1991, research published in Nature Climate Change found that approximately 37 percent of those can be attributed to manmade global warming. In the United States alone, hotter temperatures could lead to 110,000 premature deaths per year by the end of the century if warming continues unabated, a Geohealth study asserts.

One of the problems for cities is that they are hotter. The built environment both retains heat and reflects it:

Contributing factors include excess warmth generated by car engines, air conditioners and other equipment, as well as the lack of evaporative cooling from rainfall runoff that is removed by design as quickly as possible from the urban core.

Another is that typically poorer areas tend to be less protected from heat than rich areas (‘climate change is racist’, as Jeremy Williams reminds us—and also inegalitarian).

(Pinecrest, Florida (left) has a median income of $164,419, compared to $38,471 in Hialeah. And a lot more trees. Satellite images via Google Earth: image Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists).

This is because poor areas have far less tree cover than rich areas, and in American cities in particular this discrepancy can be striking:

Lack of vegetation compounds the problem for residents of hotter cities, exacerbating existing inequalities. “The heat islands in the city—the places where it gets really hot because there are no trees—are disproportionately concentrated in poor neighborhoods. And that leads to, along with a host of other factors, really negative health outcomes,” says Mario Alejandro Ariza, author of Disposable City: Miami’s Future on the Shores of Climate Catastrophe.

In response, some cities, such as Miami-Dade in Florida have appointed Chief Heat Officers. One of the first things Miami’s Chief Heat Officer, Jane Gilbert, did was to start declaring heat emergencies at slightly lower temperatures. The threshold used to be 108F (42C); now it is 105F, or just over 40C:

“Most of our heat-related deaths happen at thresholds lower than the 108 threshold, not because it’s a higher risk at the heat index of 105 or 102, but because we just have that many more days at that heat index below 108,” Gilbert says.

Miami-Dade may experience 105F degree heat for three months of the year in the near future. And again: the poor get the worst end of this:

Yes, air conditioners are nearly ubiquitous in South Florida. But the unhoused and the air conditioning insecure—anyone who must choose between putting food on the table and paying the electric bill—are still exposed to high heat index values. In prolonged power outages, like those brought on by hurricanes, the heat danger extends to everyone.

What can cities do? In real emergencies, they can move people to places like shopping centres, where the air conditioning works.

In the medium to long term, they need to plant more trees and greenery, especially in poorer areas—vegetation can reduce surface temperatures by 20C. They can also add shade into the urban mix—in playgrounds, at bus stops, and so on. It’s doesn’t have the same impact as vegetation, but as Gilbert says: “All shade is good”.

And they can also create more awareness by naming extreme heat events in the same way that storms are given names, as Sevilla has done in Spain.

The cities article comes with a couple of clever interactive diagrams. Over the course of the week the the Bulletin there will be a piece on the rise globally or air conditioning, the impact on livestock and wildlife, the effects on the body, and on the challenge that heat poses to agriculture.

2: The invention of the timeline

I’m doing a little light research into notions of time at the moment, and so found myself listening to a recent episode of Justin Smith’s ‘What Is X’ podcast in which he discussed the notion of time with the British philosopher Emily Thomas.

One of the elements that came out of their conversation was the relationship between linear portrayals of time and the application of geometry in the early parts of the Industrial Revolution.

During the conversation, one of the pair observed that it was the British scientist and radical Joseph Priestley who first developed the idea of the ‘timeline’ in 1765. That was too interesting a thought to leave dangling, so I did a little more research, and found Priestley’s first ‘chart of biography’ at the History of Information site, in all of its multicoloured glory:

(Priestley’s Chart of Biography. Via HistoryofInformation.com)

Each of the individual bars represents the life of an individual, and more than 2,000 people are fitted onto the chart:

From the site:

The Chart of Biography covers a vast timespan, from 1200 BC to 1800 AD, and includes two thousand names. Priestley organized his list into six categories: Statesman and Warriors; Divines and Metaphysicians; Mathematicians and Physicians (natural philosophers were placed here); Poets and Artists; Orators and Critics (prose fiction authors were placed here); and Historians and Antiquarians (lawyers were placed here). Priestley's 'principle of selection' was fame, not merit; therefore, as he mentions, the chart is a reflection of current opinion. He also wanted to ensure that his readers would recognize the entries on the chart.

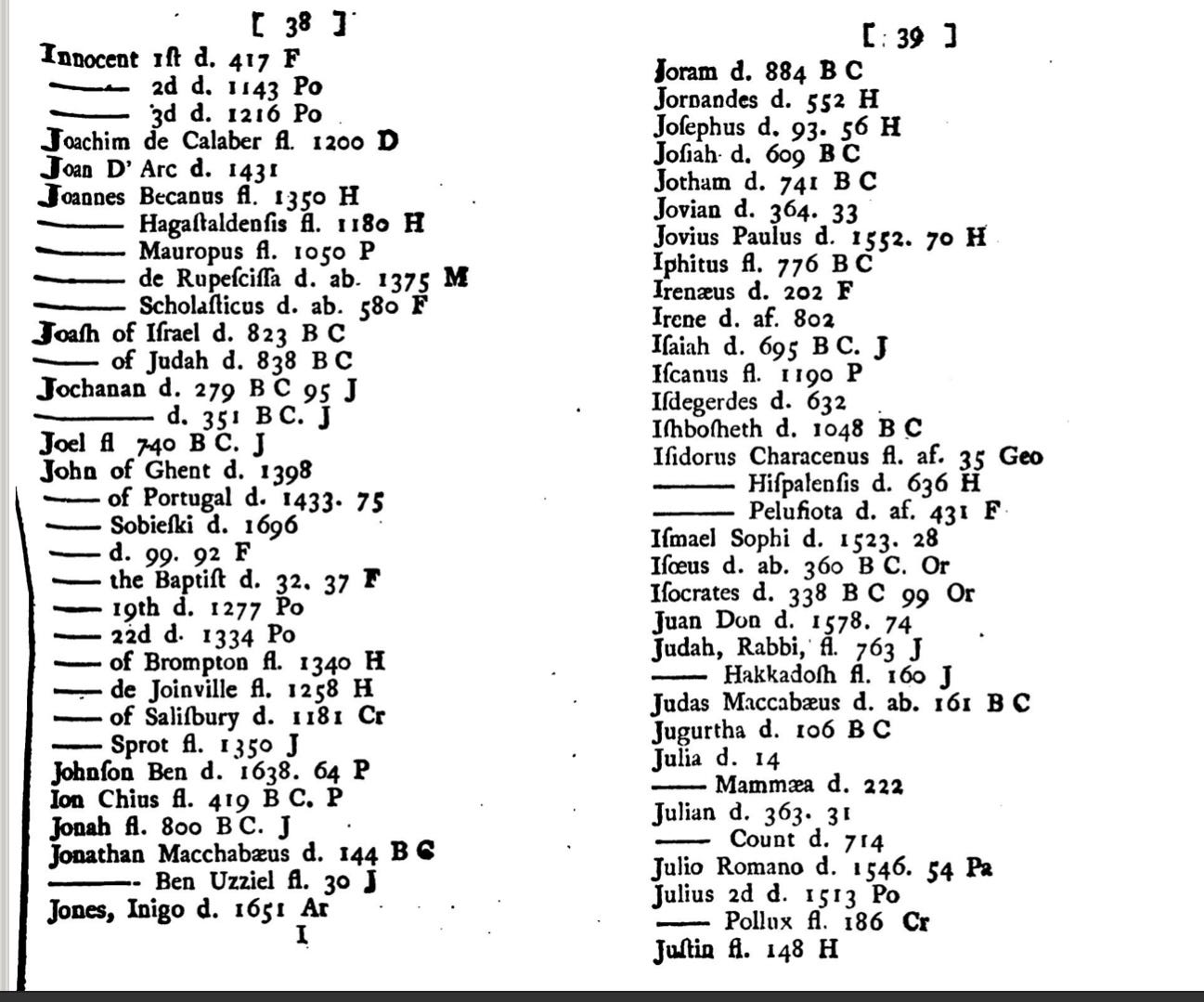

This image, taken more or less randomly from the index of an online facsimile of the book, gives a sense of the range of people on the chart:

(Online facsimile from the index of the Chart of Biography)

Priestley also published A New Chart of History, and the idea of using the horizontal axis to represent time influenced contemporaries who were also trying to visualise data, as an article in the Financial Times (possibly paywalled) notes:

William Playfair, a Scottish engineer and economist who invented the basic chart forms that still dominate the business world today (bar chart, pie chart, line chart), acknowledged Priestley’s use of the horizontal axis as an influence on his own financial time series charts.

The idea that time might exist in space, as it were, also led to the conceptualisation of time travel in the following century, notably by H.G.Wells. (Previous writers who had wanted to transport their readers to different worlds either took them to somewhere as yet undiscovered on earth, as Thomas Moore did in Utopia, or have them fall into a dream, which happens in News From Nowhere, published only a few years before The Time Machine).

Wells’ conceit in The Time Machine was that time could be conceived as the fourth dimension—effectively taking the spatial model proposed by Priestley and extending it.

There’s also an extended discussion on the podcast of McTaggart’s 1908 argument about the A-Theory and the B-Theory of time (there’s more about this on the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, and it’s quite dense). Emily Thomas notes that it is now one of the most cited papers in the field, but that it was more or less ignored for several decades, which suggests that it was comfortably ahead of its time.

A-theorists... believe that at least some important forms of change require classifying events as past, present or future. And accurately describing this kind of change requires some tensed propositions—there is a way reality is (now, presently) which is complete but was different in the past and also will be different in the future. These tensed propositions also explain why we tend to attribute significance to the past-present-future distinction.

I’ll be out of my depth if I go any further with this here (hence the research) but A-theorists tend to speak to our personal experience of time, and point to the laws of thermodynamics, which seem to imply a strong past-to-future direction to time.

On the other hand:

B-theorists think all change can be described in before-after terms. They typically portray spacetime as a spread-out manifold with events occurring at different locations... B-theorists typically emphasize how special relativity eliminates the past/present/future distinction from physical models of space and time. Thus what seems like an awkward way to express facts about time in ordinary English is actually much closer to the way we express facts about time in physics.

One of the things I took away from the podcast was the extent to which conventional futures work tends not to test much of this. There might be good reasons for this—much of futures practice is cognitively difficult enough (e.g. just talking about multiple possible futures) without stretching people’s notions of time.

And there may be swathes of literature that I haven’t come across yet. I know that the Anticipation group has started to problematise some of this, and that Anthony Hodgson discusses multiple perspectives of time in his recent book Systems Thinking for a Turbulent World. Some futures work has also drawn on indigenous views of time.

But just as our talk of ‘drivers of change’ essentially takes a Newtonian view of social change, our dominant models of of time seem to be rooted in post-Enlightenment science. The A-Theory, after all, might just be a form of social construction. So this may have consequences for some of our futures shibboleths—for example, that “there are no future facts”.

As an interviewer, Justin Smith asks good questions, but has some annoying mannerisms. Nonetheless, this podcast conversation was certainly stimulating.

j2t#347

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.