19 January 2024. Work | Van Gogh

Work, choice, and the politics of time // Dr Gachet, van Gogh and his last months [#534]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Work, choice, and the politics of time

The world of work is one of the most contested areas in current political discourse, and although people notice this, it’s often trivialised with tags like the “great resignation”, as if it’s somehow about particular employers rather than the issue of work itself.

There’s something much deeper going on. Stowe Boyd had a distinctive statistic in a post recently, from France:

Only 21% say work is very important (in 2022), compared to 24% in 2021 and 60% in 1990.

Two percentage points in a year is neither here nor there—it’s likely within the margin of error. But a forty percentage point fall in 30 years is cataclysmic, in terms of social attitudes data.

Which is a good cue for an extended review by Rachel Fraser in the Boston Review of two books written more than a hundred years apart.

The first is After Work, by Helen Hester and Nick Srnicek, published in the summer of last year. The other is The Right to be Lazy, by Paul Lafargue, first published in 1880 and recently republished.

At the heart of Fraser’s discussion is the distinction between employed or paid labour, and reproductive labour. Most of the discussion about “work” is about paid work, and much of it, or how little of it we need to do. Or, in the words of the song, “how can a poor man stand such times and live?”

(Source: Verso Books

And the gender matters there. Because a lot of Fraser’s discussion, and quite a lot of Hester and Srnicek’s book, is about the other part of our work, the reproductive labour, that is often unpaid or poorly paid, and is mostly done by women. Because a lot of the discourse that sits around reducing our paid work sits very uncomfortably around reproductive labour. Her description of what reproductive labour is will probably help here:

Cleaning, like cooking, childbearing, and breastfeeding, is a paradigm case of reproductive labor. Reproductive labor is a special form of work. It doesn’t itself produce commodities (coffee pots, silicon chips); rather, it’s the form of work that creates and maintains labor power itself, and hence makes the production of commodities possible in the first place.

And this gets mostly overlooked in discussions about the future of work for all of the obvious reasons. Most of the post-work literature gets excited about automation. Fraser mentions Oscar Wilde’s essay The Soul of Man Under Socialism, for example:

Oscar Wilde envisages a world in which “the machine” is made to “work for us in coal mines, and do all sanitary services, and be the stoker of steamers, and clean the streets, and run messages on wet days, and do anything that is tedious or distressing.”

And although she doesn’t mention Aaron Bastani’s Fully Automated Luxury Communism, it’s in the same vein, but 130 years later. The clue is in the “fully automated” bit of the title.

But as Fraser does observe, what do all those women do with their souls under socialism? Wilde doesn’t dwell on this, but Fraser’s point here is that even if we could automate breastfeeding, child-rearing and cooking, would we want to?

It’s one thing to imagine robots taking over the factory, the warehouse, and the office. But, as Hester and Srnicek point out, it’s quite another to envisage them in charge of the hospital, the nursing home, or the kindergarten. A world where no one spends tedious hours on the assembly line is a world worth aspiring to. But a world where no one nurses their children or cooks food for their friends? That sounds like a nightmare.

Some of the discussions of all of this tend to sweep reproductive labour off to the edges; it’s not paid, it’s mostly done in the home, and so on. Hester and Srnicek don’t do this; instead they talk about time: about “temporal sovereighty” and “free time”. This makes sense to me, because much of the conflict about work at the moment is about the claims it makes on our time—and indeed the way that it encroaches on our time at both ends of the labour market—zero hours contracts make our time impossible to manage, digital work and remote access endless blur the edges of the working day.

“The struggle against work,” they say, “is the fight for free time.” And free time matters because, they argue, it is only when we have free time that we can engage in activities that are chosen for their own sake: activities in which we can “recognize ourselves in what we do.”

(And as Mark Fisher wrote in his K-Punk blog,

Most political struggles at the present moment amount to a war over time.)

Fraser reads this, probably rightly, as a version of the argument about alienation from our labour being the central problem of capitalism, and Hester and Srnicek make something of the idea of what we choose freely to do:

”Laboring over a hot stove,” Hester and Srnicek write, “can take on the quality of being a freely chosen activity in the arc of a larger self-directed goal.” Hester and Srnicek, then, are not advocating indolence. For them, the problem with work is not that it is effortful. Humans are agents. We make and we do. Work, though, catches our making and doing in a trap: it is caged agency.

Writing in the 19th century, Paul Lafargue had a different perspective. He identified the same problem that Keynes tried to solve 50 years later: the workers need to buy the things that they produce. There’s always a mismatch.

In Keynes’ thinking we manage demand to ensure that workers have jobs to go to. (Although, in his essay about Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren, which I wrote about here a couple of years ago, he did imagine that we might work less as productivity increased.

Lafarge skips all of this: the way to solve this problem is just to work less. Hence the title of his essay:

Thus, Lafargue posits not so much a right to be lazy as a duty. Those who shirk it are to blame for overproduction. “The proletarians,” he writes, “have given themselves over body and soul to the vices of work (and so) they precipitate the whole of society into those industrial crises of overproduction that convulse the social organism.”

Lafargue thought that working less would encourage automation-as has happened in Japan, where the working less has been caused by demographic shift.

It is an extended review essay, and the whole thing is worth your time. But this piece is probably long enough, so I’ll just quickly summarise the way that Hester and Srnicek try to deal with this issue of reproductive work.

The first is just to lessen the burden—nobody really needs to do any ironing, for example. The second is to incorporate this care work into the idea of a flourishing life. (This is what seems to happen when people move to a four day week: their time gets taken up with forms of care that they choose to give.) But that still leaves an irreducible burden of work that needs to be done, but no-one wants to do. They suggest sharing it out.

As Fraser points out, that takes us into the realm of social relations, and she thinks that here After Work falls short:

(S)ocial relations are the real springs and cogs of justice. What really matters, when it comes to work, is not whether we can realize ourselves through it or whether we identify with its purposes.

2: Van Gogh, Dr Gachet and his last months

There’s quite a long piece by Christopher Turner at Apollo magazine on the last days of van Gogh in the care of Dr Gachet, and the history of the idea of the ‘mad genius’ that follows from that. It seems to be outside of their usual paywall.

The occasion for the article is an exhibition at Musee d’Orsay that runs until 4th February.

Van Gogh came to be in Gachet’s care after he had been consigned to a series of asylums for a year after cutting off his ear. During his time there, he wrote to his brother Theo that

“little by little, I can come to look at madness as a disease like any other’.

Gachet believed that the mentally ill should not be isolated from society, but should also “work a great deal, boldly”. He was a painter himself, and well-connected with many of the artists in the Impressionist movement, and others. Through this, he amassed a fine collection of their paintings.

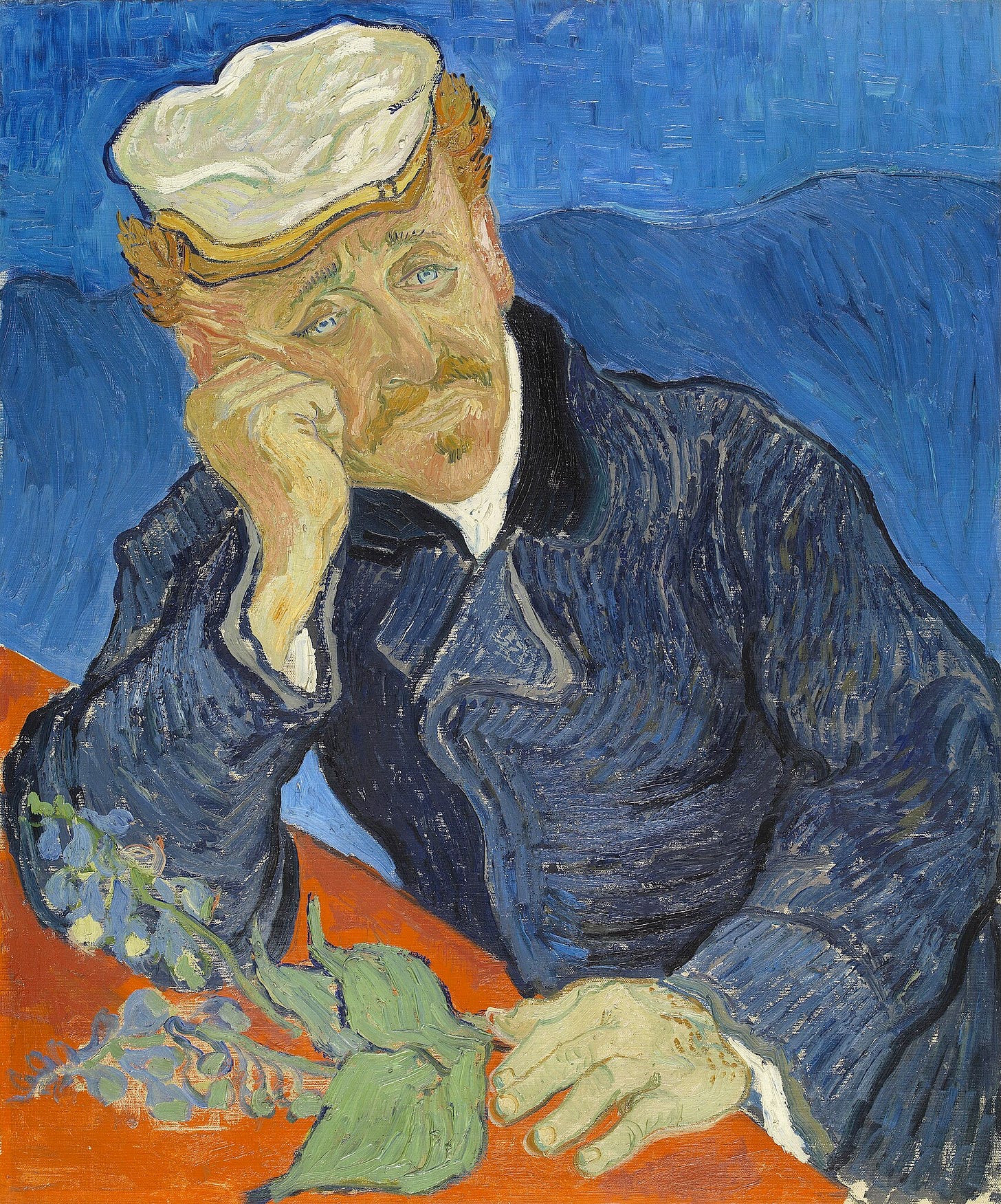

(Vincent Van Gogh, Doctor Paul Gachet. 1890. Musee d’Orsay)

After van Gogh was discharged from the Saint-Paul asylum, which believed him cured, the artist put himself into the care of Dr. Gachet, partly because he thought it meant he was less likely to be arrested and returned to the asylum if he had another attack. He took cheap lodgings in the same village. And, of course, he worked a great deal:

The artist completed almost a canvas a day in his final months in Auvers-sur-Oise, 30 kilometres north-west of Paris.

Gachet had written a thesis on melancholia, and had worked in a number of asylums, sometimes sketching patients, including a woman in a straitjacket at the hospital in Gentilly, where the device was invented. He visited the engraver Charles Meryon in the asylum at Charenton, and diagnosed him as having delirious melancholia:

Meryon sometimes refused to leave his bed, thinking himself marooned in a sea of blood, and had paranoid fears about a Jesuit conspiracy. He was furnished with a studio and added curious monsters, horse-drawn chariots and flying fish into the skies of his pathological cityscapes.

Van Gogh knew of Meryon, although he write to his brother that

‘I keep thinking of so many other artists suffering mentally, and I tell myself that this does not prevent one from exercising the painter’s profession as if nothing were amiss’,

which was Gachet’s prescription against melancholia. But he also wrote that he risked his life for his work and that “my reason has half-foundered with it”.

This is the foundation of the idea of van Gogh as being the epitome of the mad artistic genius, cemented in popular culture by Vincente Minelli’s film Lust for Life. The Apollo article cautions against this idea:

His distinctive style was developed before any bouts of schizophrenia or manic depression and few in his lifetime made the equation between his mental illness and his work.

But there is also a long history of dismissing modern art as the work of the mad. Van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr Gachet became one of the first of his works to enter a public museum, in Frankfurt, in 1911, but when the Nazis came to power they branded the work as ‘degenerate’—this was even before they held their notorious exhibition of ‘degenerate art’. It was sold by Goering in 1937.

But as the article also notes:

At the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874, Cézanne’s A Modern Olympia, which Gachet owned and had loaned, was dismissed by a reactionary critic as the work of a ‘lunatic, painting under the effects of delirium tremens’.

Gachet himself suffered from depression, which van Gogh attributed to the death of his wife 15 years ago. But he seems to have been fragile enough for van Gogh to notice. He wrote to his brother:

‘he is sicker than I am, I think (…) Now when one blind man leads another blind man, don’t they both fall into the ditch?’

Gachet was, apparently, surprised when van Gogh shot himself, and looked after him for two days until he died. When Gachet told the artist he hoped to save him, van Gogh told him that in that case he would have to do it all over again.

There’s some evidence that Gachet identified with van Gogh.

He sketched the artist on his deathbed and in a letter of condolence to Theo he compared the artist to the Stoic philosopher Seneca, who also committed suicide and suffered a slow death by bleeding. He described Van Gogh as having a proud ‘sovereign disdain for life’ and admitted that he too was sometimes tempted by ‘the void’ that had consumed him.

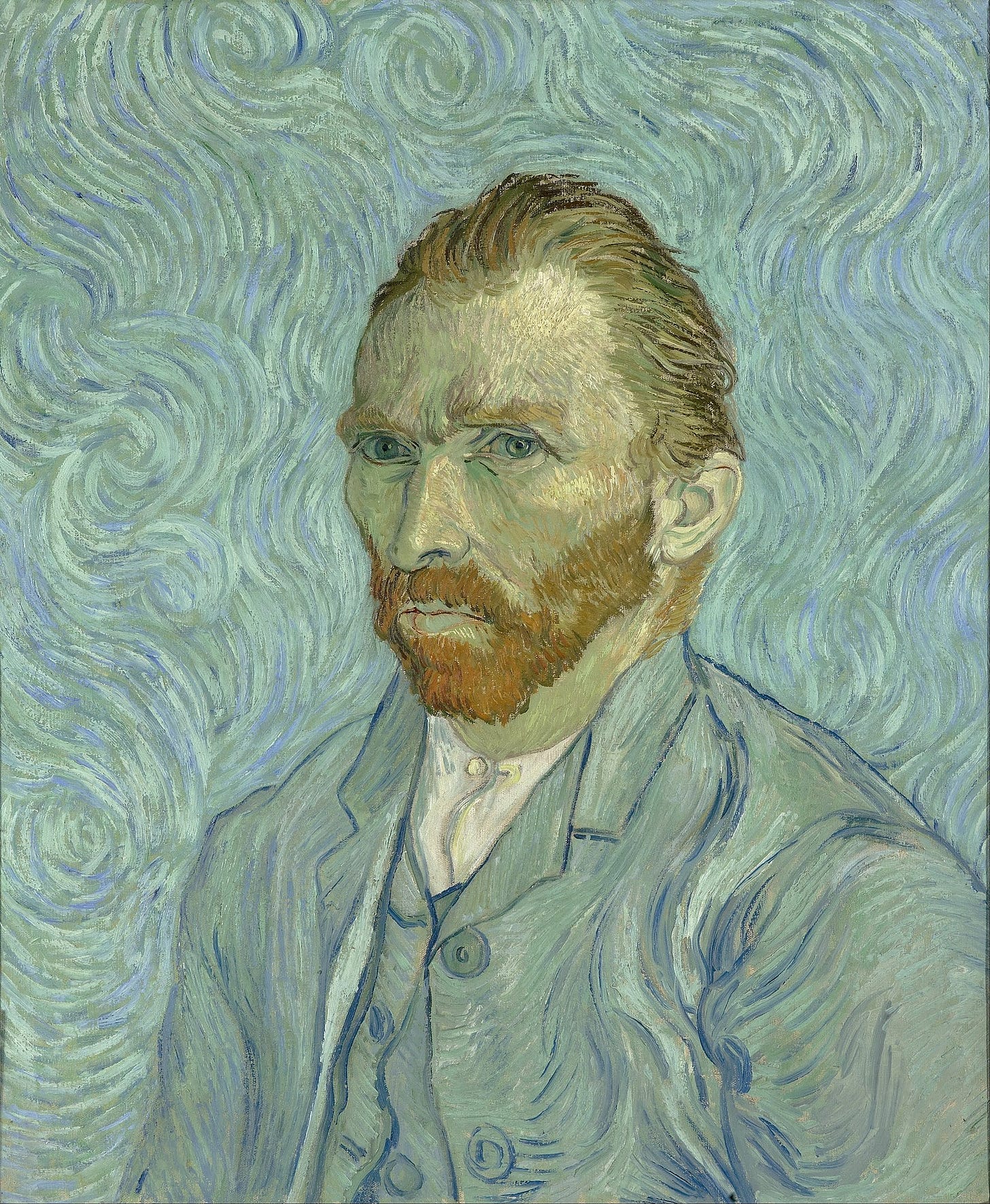

(Vincent van Gogh, Self portrait, 1889. Musee d’Orsay)

When Theo’s wife published the letters between the two brothers she said that no-one understood Vincent as Gachet had done. Gachet devoted his last years to writing an unpublished biography. In 1905, for the only time, he loaned two van Gogh portraits to an exhibition, one a painting of the doctor, one a self-portrait of the artist.

These were the portrait of himself with a grief-furrowed face and the self-portrait the artist had made in Saint-Rémy the year before, his head haloed in blue swirls, which Gachet acquired from Theo right after the artist’s death. It was as if he wanted to link himself irrevocably with Van Gogh, as a kind of alter ego and witness to his final days. The melancholy, red-headed doppelgängers, Van Gogh wrote, were painted with the ‘same sentiment’.

Other writing: Brains and ballads

Lenin’s brain

Peter Curry has a new post at his King Cnut Substack on the long and often controversial project of trying to deduce intelligence from brain size and other measurements. Since we’re only a few days away from the centenary of Lenin’s death, let me share an extract about the research on his brain after his death:

(T)he Soviet High Command decided to prove that (Lenin) was a genius via brain analysis. To do this, they asked the preeminent anatomist of the time, Oskar Vogt, who was based in a Berlin laboratory, to examine Lenin’s brain. The information about this program is conflicting. Multiple sources differ on whether Vogt had access to the entire brain or a tiny slice of frontal cortex, and how exactly he performed his analysis. He seems to have been shown the entire brain in Moscow, but then only been allowed to take one cortical slice back home to Berlin.

The whole post is here.

Music: Tam Lin and Benjamin Zephaniah

At Salut! Live I have been writing about the old Scottish ballad Tam Lin, as a belated way of acknowledging both Benjamin Zephaniah and the musician and producer Simon Emmerson, who both died last year:

Tam Lin is one of the oldest ballads in the British repertoire... It is a tale of Scottish magic The idea of getting Benjamin Zephaniah to rewrite and record Tam Lin came from Martin Carthy. Emmerson visited Cecil Sharp House with Tim Whelan of Transglobal Underground, and met the Vaughan Williams librarian Malcolm Taylor, who helped with the task.

Zephaniah updates this story—hence the new title of Tam Lyn Retold—and in his retelling, Tam Lyn is a refugee who faces deportation. There’s a magical twist here too, in the Immigration Tribunal.

j2t#534

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.