19 December 2023. Work | Politics

Business, time, innovation and culture change. // How populism works. [#526]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Business, time, innovation and culture change.

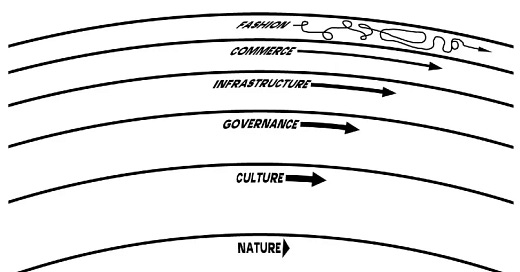

At his Substack, Stowe Boyd has had the interesting idea of using Stewart Brand’s pace layers model to think about work. Brand developed the idea of pace layers from the thinking of Freeman Dyson, and first applied it to buildings in his book How Buildings Learn, and then to societies in The Clock of the Long Now. Here’s the model for societies.

(Source: Stewart Brand: The Clock of the Long Now)

Here’s Brand’s description of the principles of the pace layers.

From the fastest layers to the slowest layers in the system, the relationship can be described as follows:

Fast learns, slow remembers. Fast proposes, slow disposes. Fast is discontinuous, slow is continuous. Fast and small instructs slow and big by accrued innovation and by occasional revolution. Slow and big controls small and fast by constraint and constancy. Fast gets all our attention, slow has all the power.

All durable dynamic systems have this sort of structure. It is what makes them adaptable and robust.

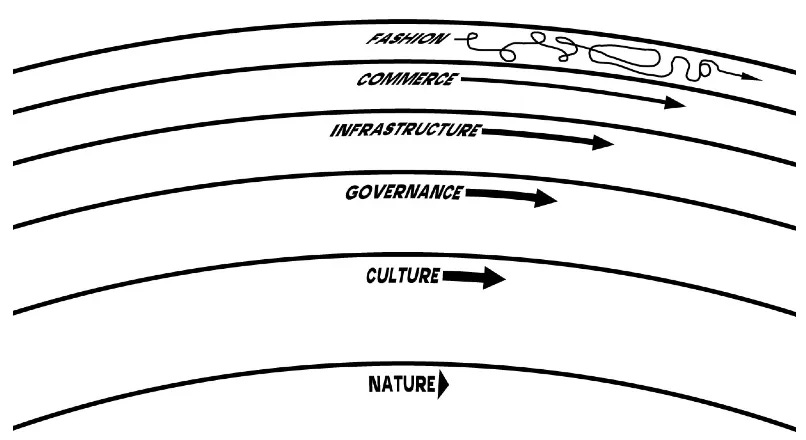

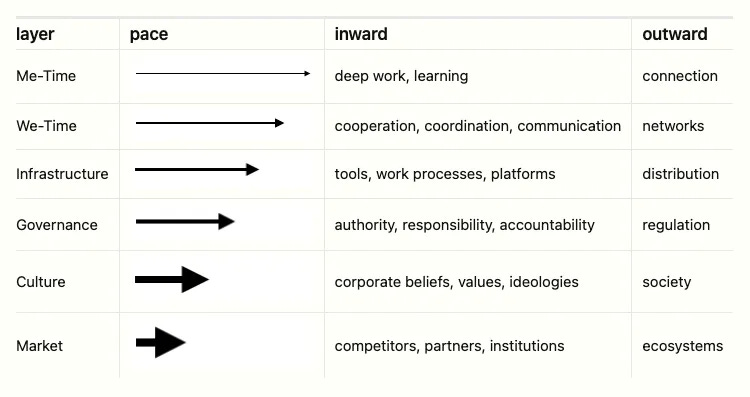

Boyd’s article also includes Brand’s table of how these work. The length and weight of the arrows represent speed and power, in that order.

(Stewart Brand, Pace Layers of Civilisation)

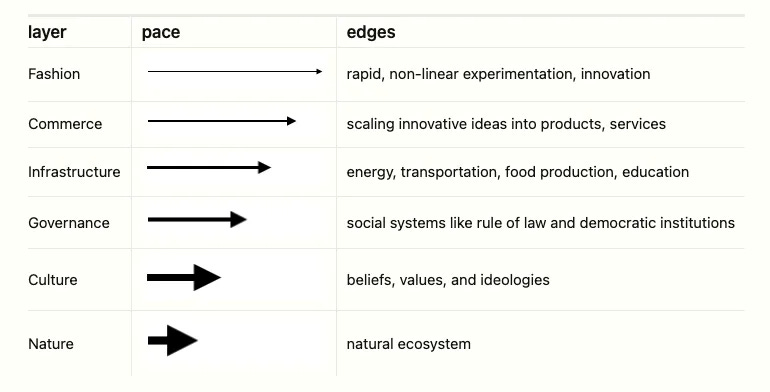

So Boyd adapted this to match some of his own writing. A couple of lines of explanation first, since he changed a coule of the labels.

I have included the terms ‘me-time’ and ‘we-time’ from Fighting for Time and True Asynch , where they are synonyms for ‘individual deep work’ and ‘group cooperative work’, respectively.

He has also added a column, “adding a distinction between the inward-centered and the outward focuses of each layer.”

(Stowe Boyd, Pace Layers of Work)

Boyd is thinking about this through the lens of innovation, specifically business innovation, and so he starts with the individual and “deep work”, which is a theme of his. Then it moves from the individual to the group, which might build on it or might reject it. (Fast proposes, slow disposes.)

And so innovations spread through the business, and perhaps into the wider market:

But at every interface, slow has the power, while fast gets the attention.

Boyd is using this as a way to understand why so much innovation fails, and also why so much cultural change in businesses fails:

To succeed, some group has to formulate a change plan, and then push down through the pace layers of work, fighting the inherent (and inescapable) inertia of each deeper level. This requires ongoing and constantly renewed pushing, where individuals have to convince groups to buy in, groups to build corresponding infrastructure, for governance models to adapt to new ways of doing things, and causing widespread shifts in cultural beliefs.

80% of change initiatives fail. In fact, as he says, when you look at it this way it is astonishing that 20% succeed.

And it also helps to understand why a new CEO who wants to change the culture finds it such a struggle. They’re starting from a long way down the system, in among the slow parts.

(W)hen a new CEO comes aboard and wants to decrease high degrees of damaging burnout, she may have a yearslong campaign ahead of her, since workers across the company have internalized the ethical system of overwork, deeply, and it influences hiring, promotion, planning, and everything else it touches.

If I have a criticism of this, it’s that the ‘market’ level is too far down. They are a form of regulation: markets are rule-based systems, which should be sitting alongside the regulation layer. (Who benefits from them depends on the way that the rules are configured, which tends to be shaped by the culture layer below.)

But anyway, they’re only ‘ecosystems’ in that lightweight version of the business’ transactional/operating environment that the shiny shoe management consultants talk about when they’re trying to make business seem more complicated than it is. And the culture layer should probably have ethics in it, although you can’t fit everything into a box in a diagram.

The layer below the culture layer ought to be the nature layer, since we know from other models—Kate Raworth’s Doughnut model, for example—that the limits on business come from nature. And nature, of course, is the slow layer that will be shaping businesses in quite drastic ways if business doesn’t adapt.

The post is part of three part series on the relationship between work and time. The first post is here. The third one is due in the next few days.

2: How populism works

It was International Migrants’ Day yesterday, and by chance I had spent some of the weekend working on a draft of a report on migration. The usual adjective to describe the politics around migration is “toxic”, and the reason for this is broadly because far-right populists, across Europe, have found it a useful way to catalyse support.

Of course, it’s more complicated than that, and I’m not going to rehearse the argument in the report—it’s a couple of months before the final version will appear—but one of the things you understand quite quickly is that many of the things that would improve the lives of migrants would also improve the lives of poorer workers in the bottom quartile. (Better quality labour markets, for example).

Some of this is because—and this is a diversion from my story here—migration happens in response to labour demand, rather than being an extra supply, which is why it has almost no impact on wage levels. And so the only people who benefit from undocumented workers are employers, especially unscrupulous ones.

So this is an extra long way of saying that having spent some of my weekend on the relationship between populism and migration, I was interested to come across a reference to Eva Illouz’ book The Emotional Life of Populism, which tries to work out why people who don’t benefit from right-wing politics are willing to support it.

The book was published earlier this year, and I found an extract onlinefrom The Montreal Review:

In my book I argue that populist politics blends together four specific emotions – fear, disgust, resentment, and love – and makes these emotions dominant vectors of the political process. The mixture of these emotions forms the matrix of populism because they generate antagonism between social groups inside society and alienation from the institutions that safeguard democracy.

Populism lives somewhere in the space between reality and fear. Part of what populists do is to name real issues that affect parts of the working class. The other is to create a permanent state of fear, which involves maintaining whole groups within and outside of society as “the other”. This has consequences for political rhetoric and strategy:

Fear provides compelling motivation to repeatedly name enemies as well as invent them, to view such enemies as fixed and unchanging, to shift politics from conflict resolution to a state of permanent vigilance to threats, even at the price of suspending the rule of law... (Populists) all express fear of a shifting balance of power between majority (racial, ethnic, religious) and minorities and has become existential, about the very existence of the nation.

The second part of the quartet, disgust, stems from the first. Disgust, she writes,

creates and maintains the dynamic of distancing between social groups through the fear of pollution and contamination: it helps separate ethnic or religious minorities and, by the logic of contamination, it also contributes towards separating the political groups who either support or oppose the minorities.

Self-victimisation is an important part of this process. Ressentiment is a form of hostility that is directed toward an object that one identifies as the cause of one's frustration, in a way that allows you to blame it for that frustration. Illouz writes that

it redefines the political self in terms of its wounds... When all groups are victims of each other, it creates antagonism and changes ordinary notions of justice.

Of course, those wounds are created by those others, which means that ordinary politics, which require dialogue and negotiation, become impossible.

And, of course, this is a form of in-group politics that requires its members to to believe that they belong—especially to a version of the nation—and that all of these others don’t. They are dangerous members of the nation, or even “citizens of nowhere”, in former UK Prime Minster Theresa May’s insidious phrase (she was a non-populist leader of a populist party).

We should not underestimate the deep relationship that nationalism entertains today with religion and tradition. Trump’s white supremacists, Giorgia Meloni, Orbán – all claim that their countries and nations must defend their Christianity against atheists and non-Christians. They also call for a return to traditional family values and oppose gender politics and reforms that would bring equality to homosexuals.

In Illouz’ framing, this cocktail creates large imaginary spaces in which conflict is fuelled by unavenged wounds inflicted by imaginary enemies who do not share your authentic view of the nation or its people.

All of these emotions, together, create large imaginary spaces impervious to the real; these spaces are filled by emotional projections and scenarios which become prone to a paranoid interpretation of social and political life.

Illouz is Israeli, and much of her thinking about populism has emerged from watching the construction of far-right populism in Israel. But it’s also clear that she regards this as only a particular case of a more general phenomenon, albeit one with endless national flavours:

populism must be understood in the plural mode: its expressions vary from country to country and do not always arise from the same reasons.

There are some similarities here. There’s a contradiction around democracy, for populists uphold democracy, at least at the level of rhetoric, while doing whatever they can to subvert democratic values such as “fair institutions”. Populism is also “masculinist” even when it has femaile leaders such as Meloni. Illouz describes this as a form of “gender washing”. And it is “anti-cosmopolitan, anti-globalist, and anti-European”:

This deep suspicion of outside cultural forces goes hand in hand with an affirmation of one’s primordial cultural identity, which is antithetical to the supposed recourse to international law of “elites,” courts and norms.

Mention of elites points to the biggest trick that the populists have managed to perform:

leaders from the extreme right have successfully severed the traditional relationship of the left with the working classes and have cast it as representing the elites. If there is one process which the Israeli case illustrates most cogently, it is exactly this: the conflation of a left-wing agenda (based on universalism, human rights, redistributive justice, and cultural pluralism) with “elitism” and with the idea that the elites no longer care (or never cared) for their own people.

What this creates is a set of familiar tensions. Between the “populist” periphery and the “elite” core, for example; between an idea of “the family” and values around gender autonomy and reproductive rights; between an idea of “the nation” and forms of internationalism.

One of the critical ways that this set of beliefs is maintained is through strong codes of good and bad, which are used to police the edge of the in-group and to create conflict around political solutions to problems that might undermine the populist base. On migration, for example:

Populist leaders know to recode problems to be solved by experts (for example, how much immigration should or should not be encouraged for the economy) into moral ones (how much immigrants threaten our way of life).

But she suggests, the progressive left has recast political problems in the same way, but from a different set of perspectives. It has, she says,

entirely recoded social problems into moral struggles and economic policy into identity, a fact that explains why the political terrain has become so polarized and why it is now played on the terrain of morality.

I’m never sure about this argument, to be honest. I see plenty of parts of the progressive left working hard at projects that are about relatively old-fashioned elements of social, economic, and climate justice, in the workplace and in communities. And the whole point of intersectionality is that identity is only ever a marker for other inter-connected forms of disadvantage. But the fact that this view is so widespread—she’s not the only person to express it, by any means—says something about the success of populists in recasting politics as morality.

j2t#526

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.