Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: Why “intelligence” fails

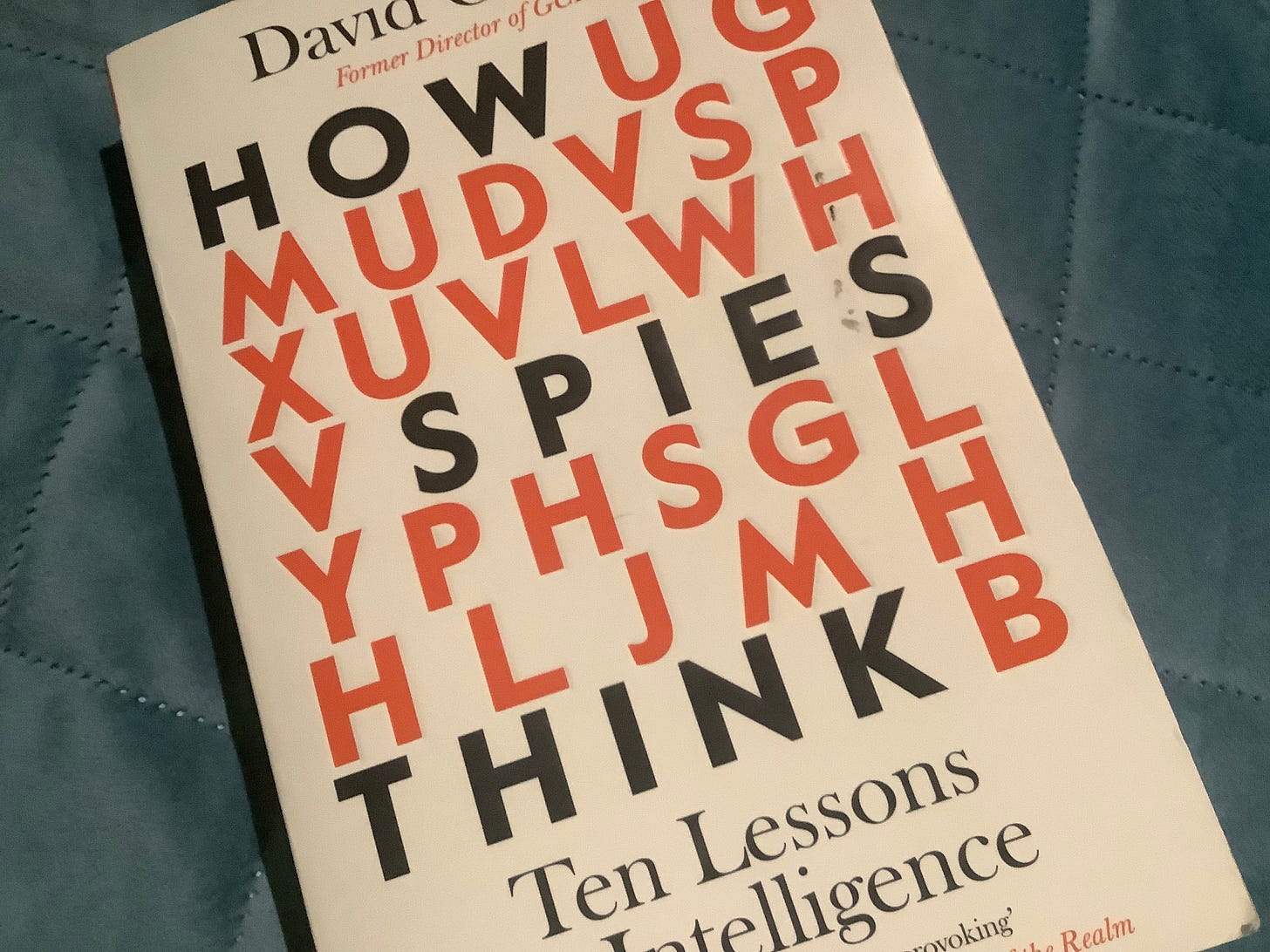

It was an odd experience to be reading David Omand’s book How Spies Think during the American departure from Afghanistan, prefaced by what Paul Rogers called (in Open Democracy) “appalling intelligence failures by the US, the British and their NATO allies”.

Omand is, if you like, the urbane face of intelligence, after a career spent in and out of places like GCHQ, the Ministry of Defence, and the Home Office. These days he lectures at King’s College London and serves on the boards of a couple of arms companies, according to Wikipedia.

How Spies Think lays out a structured approach to “intelligence” that is supposed to improve the use of evidence in intelligence analysis and to reduce the risks of blindspots and groupthink.

This is the four-stage SEES model: first, Situational Awareness; then Explanation; then Estimate and Model; then Strategic Notice. (There’s something about the defence and security industries that loves these sorts of acronyms.)

Here’s an extract from the article linked just above:

Situational awareness: the “what, when, where” type of facts that show what is happening. “We need reliable, consistent situational awareness of what we face, before we start arguing about what policy choices we may have.”...

Explanation: the “how and why”. Facts can be interpreted in different ways, so all possible options need testing. “Providing a sound evidence-based explanation involves methodically testing alternative hypotheses against the data.”...

Estimate and model. This step asks: what will happen if we take a particular line or act in a certain way?...

Strategic notice. This refers to the “possible future challenges that might come and hit us, especially when we are pre-occupied with the current crisis”. Such foresight helps governments prepare for – and even avert – long-term risks...

And on the face of it, this all seems sensible enough. It doesn’t’ seem to be that far away from a typical futures approach that would start by Scanning and sensing, then would order the data, then investigate the implications, and then decide how to act.

But, but, but... Although I haven’t got the time here to do a full review, there’s a lot of spurious process in the detail in the book that attempts to reduce complexity to probabilities.

Stage 2, for example, depends on lots of Bayesian inference as a way to get to likelihood. There’s not much space here for the sort of emergence you see in complexity.

Which in turn, I’d say, means that there’s not much in the estimate and modelling stage that allows for resilience in response; a lot of potential options appear, on my reading, to have been closed off by the end of Stage 2.

There’s also not much room for the bigger picture. Omand spends a lot of time on the threat to democracies of digital subversion, as he puts it in some places (it’s “digital sedition” on other places). But he spends no time at all on the economic destruction caused by the pursuit of shareholder value and the enclosure of public assets by finance capital that creates an arena for such destabilisation.

There’s precious little upframing here, in other words.

Which is a long way back to Paul Rogers, who has over a long period of time been a measured voice on security, largely because he sits a long way outside of the security establishment in the department of Peace Studies at Bradford University.

It may be relevant that he has to do most of his thinking by using what the intelligence services would call “open source” information—published material, in other words—rather than “secret” information, which seems repeatedly to lead to errors of judgment (as for example in the case of Iraq’s non-existent weapons of mass destruction).

Rogers notes that the wider jihadi movement barely needs a Taliban government in Afghanistan to prosper, because climate change and COVID-19 will do the job of radicalisation just fine.

On COVID, the less than half-hearted attempts by Western governments and pharma companies to enable the distribution of vaccines to the poorer world has caused resentment.

The acceleration of climate change is similarly going to have far more disruptive effects on the poor world than the rich world, which will “exacerbate the risk of revolts from the margins.” He continues:

Unless the elites of the world transform their understanding of security, things are going to look good for extreme movements in the 2030s and beyond, whether they stem from perverse religious identities, ethnicities, nationalisms or political ideologies.

But you don’t get any sense of this from reading How Spies Think.

#2: Paying for rainforests

Gabon has become the first African country to be paid for preserve its rainforests, under a pioneering scheme underwritten by Norway.

It works like this.

Norway has committed $150 million to pay Gabon if it protects its rainforests by reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation (REDD+), and the first payment, of $17 million, was made earlier this year.

(88% of Gabon is covered in tropical rainforest. Image by jbdodane via Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0).

The article is stuffed full of acronyms—it’s almost as if we’re not meant to understand the processes that are designed to slow global warming. But REDD+ works something like this:

The idea that underpins REDD+ is that developing nations should be able to financially benefit from the ecosystem services that their forests provide, such as carbon storage and as reservoirs of biodiversity. The REDD+ concept has been around since 2005 and trialed in various forms, with varying degrees of success.

Gabon is a relatively unusual case. It is sparsely populated, with a population concentrated in its cities. Oil revenues, now declining, have underpinned the economy, so it hasn’t needed to plunder its forests. But most of its food is imported, and it is trying to use ecosystem services as a way to support its economy. It plans to use the forests in a sustainable way, and to keep the value of processing its timber in the country. But we all need its rainforests to be preserved, desperately:

What is undeniable is the value of the Congo Basin and the global consequences if countries like Gabon cannot find a way to achieve the development they need without sacrificing their rainforest.

“The Gabonese and Congolese forests help to create the rainfall in the Sahel, so if we lose the Congo Basin we lose rainfall across Africa,” (Gabon’s Minister of Forests, Lee) White said. “If we lose the carbon stocks in the Congo Basin, which represent about 10 years of global emissions of CO2, we lose the fight against climate change.”

j2t#151

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.