19 April 2022. Finance | Cars

The curse of the finance sector // The future that’s already happened for internal combustion engine parts

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

(Oh, and welcome back after my mini-break last week.)

1: The finance curse and Britain’s political economy

I read The Finance Curse a while ago but have only just got round to constructing a review. The book, by Nicholas Shaxson, was published in 2018, and is about the effects of an over-developed finance sector on the British economy. As you read it, you realise also that it explains the political economy of the United Kingdom. (I’m told that something similar happens with Oliver Bullough’s two books on the same theme—Moneyland and Butler to the World—but I haven’t read these.) The review got a bit extended, so I’m splitting it over two days.

(Photo: Andrew Curry. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

By political economy, I mean that it describes the workings of the UK in a way that makes otherwise apparently irrational political decisions make sense, at least on their own terms.

In short, the book suggests that the UK economy has a financial sector that is about significantly larger than it needs to be to service the productive parts of the economy, and the effects of this are almost completely extractive.

The history is striking. Until 1970, the UK’s finance sector’s assets were worth about 50% of UK GDP. By 2007, this had reached 500%—around twice the average for Europe, four or five times the ratio for the United States.

The result is that the City of London, in effect, is a leech that sits on the economy and takes a cut wherever it can. And second, public policy decisions and public institutions routinely privilege this behaviour.

To take one example (this is mine not his): one of the reasons that the UK opted for an unwieldy student loan scheme to pump money into the university sector, rather than a simpler and cleaner graduate tax, is because it creates a loan book that needs servicing.

Or, come to that, why Britain implements a complicated and unhelpful ‘loan’ on behalf of its energy companies while France merely slaps a windfall tax on excess profits.

I realise that this story is almost the exact opposite of the one that is usually told about the City of London. If I had a tenner for every story I’ve read from some City flack about how the City of London props up the British economy because of the taxes that it pays, I would probably be writing this on the verandah of my place in the Cayman Islands.

Shaxson reminds us of all of this noise, and also reminds us that it is now completeely institutionalised. After the financial crisis, the then Chancellor of the Exchequer (UK Finance Minister) Alistair Darling and the Treasury set up TheCityUK, in the face of public anger about the role the banks had played in the crisis, and little they had been affected by this. Although created by the government, it was run by the City of London Corporation, as—in Shaxson’s words, “a one stop shot for financial lobbying (p258).”

This closeness goes back a long way: the City of London also an official—“the remembrancer”—who has the right to sit on the floor of the House of Commons in the eyeline of the Speaker of the House, to keep an eye on things. The history of how the City of London came to be a facilitator of offshore finance—which largely sits behind this story—is about a deliberate act of policy promoted by the Treasury to offset the relative decline in London’s importance after the war.

So it’s probably worth backing up a bit.

The idea of the “finance curse” is a metaphor taken from another metaphor, that of the “oil curse”. The “oil curse” is the observation that most economies that have discovered oil have been wrecked by it—with the notable exception of Norway. (That’s a post for another day). This is counter-intuitive, since finding oil historically has basically been like finding free money in a hole in the ground.

Shaxson, who worked as a reporter in Angola during its oil boom, says it works like this:

their natural resource abundance seemed to result in slower economic growth, more corruption, more conflict, more authoritarian politics and greater poverty than their resource-poor peers... The big point is that all of this mone flowing from their natural resource endowments can make their populations even worse off than if the riches had never been discovered (p5).

So, similarly, the finance curse. Financial sectors do have a function in a well-ordered economy: they channel investment towards more productive activities, they spread risk, and so on.

But when they are over-blown—and the UK finance sector is vastly over-blown, given the size of the economy—they start to become self-serving. They need to extract value to maintain themselves:

Once a finance sector grows above an optimal size, and beyond its useful roles, it begins to harm the country that hosts it. Finance turns away from its traditional role service society and creating wealth, and towards often more profitable activities to extract wealth from other parts of the economy. It also becomes politically powerful, shaping laws and rules and even society to suit it. The results include lower economic growth,steeper inequality, inefficient markets, damage to public services worse corruption, the hollowing out of alternative economic sectors, and widespread damage to society and democracy.

Well, for anyone who follows the state of the UK, that seems like a pretty familiar list. In tomorrow’s Just Two Things, I’ll discuss how the mechanism works, and what the policy implications are.

2: The future that’s already happened for internal combustion engine parts

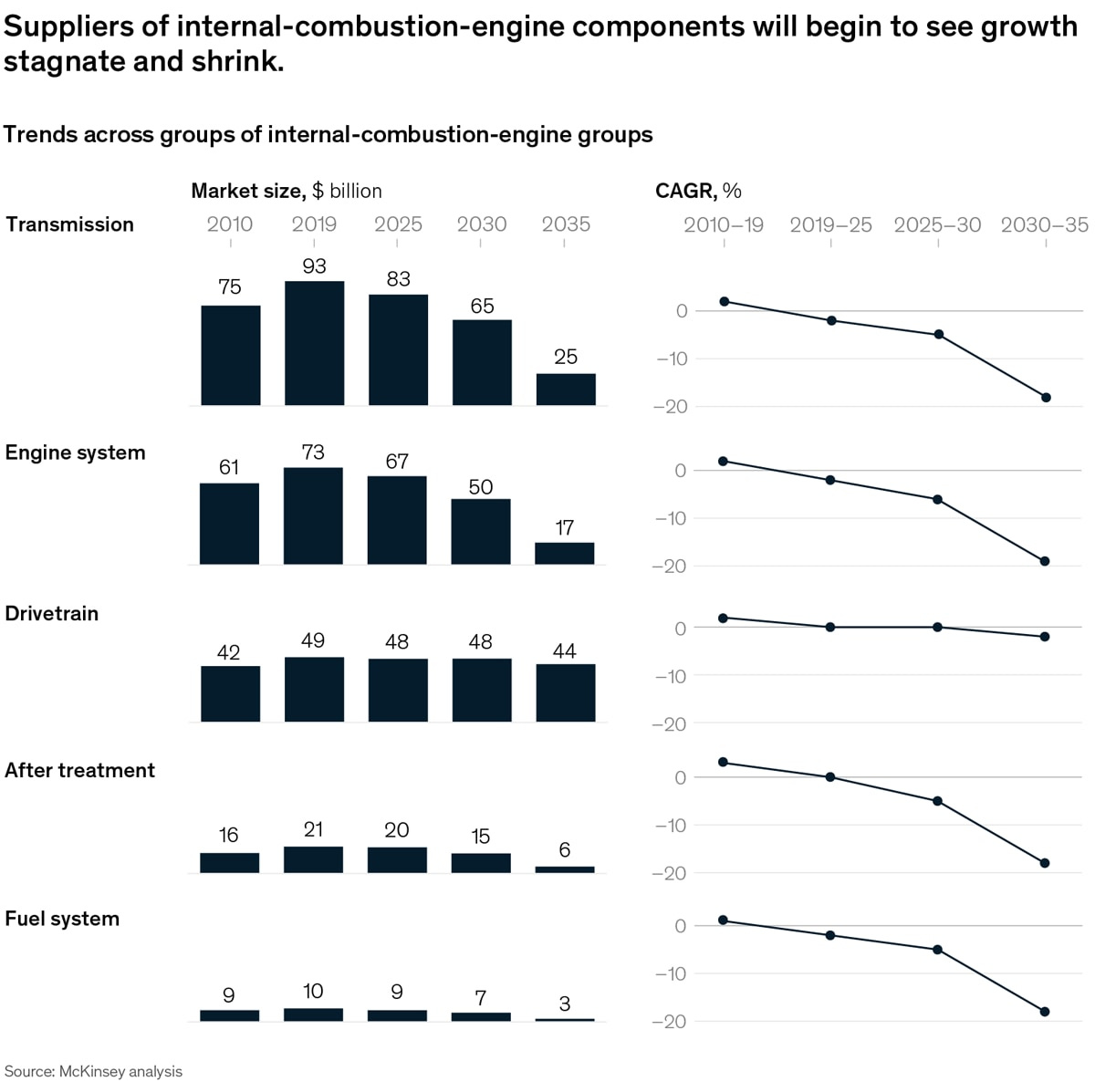

McKinsey has done a bit of analysis forecasting demand for internal combustion engine (ICE) suppliers, and obviously concludes that most types of demand are heading downward. It has one of those recklessly precise charts that breaks the data out over different types of service type. Reading between the lines, it’s probably global data, but the article is shockingly vague on this point.

Given the general projections for demand for electric vehicles, with their vastly simpler engines (a handful of moving parts as against 10,000 or so), these rates of decline make sense, although analysts such as Gregor MacDonald would probably suggest they should be steeper—the market may reach a tipping point more quickly than this. (Also: once this cycle starts, it accelerates, as everything involving an ICE vehicle gets harder to do). Whichever way you position it, this is “a future that has already happened”, to borrow Peter Drucker’s phrase.

The piece generally is a ‘come and get me’ plea to companies that might need some of McKinsey’s consulting magic (yes, irony off) to help them manage their decline more effectively.

One of the things it made me think about was the secondary market for repairs, which is also likely to show steady declines—albeit as a bit of a lagging indicator. Engines apart, the repair market for combustion engines is going to take a downward turn, but there’s still going to be a chunk of garage work that needs doing, such as bodywork repairs, windscreens, smashed lights, tyres, brakes, and so on. Garages—at least in the UK—will likely continue to give cars annual roadworthiness certificates on behalf of the government.

I don’t have a breakdown for what these are worth, but overall the market is going to shrink. For garages there might also be some quite big bets to be made. There’s going to come a point where an investment in a tens-of-thousands of pounds diagnostic system for the engine of a particular manufacturer’s ICE vehicles may no longer be worth the cost because the returns won’t be high enough.

j2t#299

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.