18 October 2023. Sustainability | Technology

Taking stock of sustainability // The geo-politics of global tech regimes (#505)

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Taking stock of sustainability

Gillian Tett, the Financial Times journalist who launched the paper’s Moral Money newsletter in 2019, has been appointed as the Provost of King’s College, Cambridge, which means she’s stepping back from most of her journalism commitments, including Moral Money.

In her final contribution, she took stock of what had happened over those four years. Although it’s behind the FT’s paywall (I think), there’s some interesting points in here that are worth sharing, in particular about the ESG (Environment/ Social/ Governance) agenda.

The first is that the hunch the MM team had in 2019 that sustainability was ready to jump out of the shadows into the journalistic mainstream has been proved correct. She suggests that there have been several phases to this growth:

In 2019, Moral Money readers wanted to understand the “why” of ESG. In 2020, as these ideas went mainstream, there was more demand for the “how”. So we reported on the struggle to create credible ratings, accounting frameworks, talent pipelines and so on. This tale continues since... This year, however, the focus has shifted again: ESG has been weaponised. That is partly down to rising energy costs after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It also reflects a rightwing hunt for political weapons to use against the left.

And this is a depressing litany, whether it is US Republican state legislatures trying to push through legislation to restrict or prevent ESG investing, or Rishi Sunak in the UK winding up rhetoric that undermines climate change investment, or anti-ESG sentiment in the Netherlands.

As she points out, when she talks to scientists in her new job in Cambridge, and heaven knows we shouldn’t have to say this, they are unanimously clear on the risks of two degrees of warming.

(Photo: Alisdare Hickson. CC BY-SA 2.0)

Tett says that in 2019, she had hoped that climate change might create greater international co-operation, but this doesn’t seem to have happened. Instead we have seen conflict between the Global South and the Global North over the North’s responsibility to reduce emissions, and economic competition between countries to secure the critical minerals for the post-carbon transition.

But, she says, there are signs of change. I hadn’t come across Andrew Forrest before, but he is the chief executive of the Australian mining group Fortescue, and perhaps further evidence that climate champions can pop up in unlikely places. He has been touring European universities:

He is seeking to build public support for a campaign to stop climate change by illuminating the threat of deadly humidity. He is also appealing for countries such as China and the US to remove all tariffs on the trade in green minerals and tech. The IMF agrees: its new World Economic Outlook calls for the creation of a tariff-free “green corridor” in global supply chains to enable a more co-ordinated fight against climate change.

It sounds like a no-brainer, but like other such ideas that might accelerate the green transition, it won’t happen soon, because—more conflict—green supply chains are an area of geo-political competition, as the adjacency of the words “China” and “the US” in quote above might suggest.

All the same, Tett does identify some reasons to be cheerful—four of them in fact, which sounds like a cue for an Ian Dury song.

The first of these is that although right-wingers have spent time criticising ESG, and introducing proposed legislation, they haven’t proposed a coherent alternative,

or called explicitly for a return to the shareholder-only mantra of Milton Friedman. I think this is because even rightwing commentators know that it is unrealistic to expect businesses to ignore the social, political and environmental context in which they operate.... If Friedman were alive today, I suspect he would argue that companies should watch stakeholders too, to protect shareholders’ interests.

And a lot of those US Republican bills have failed or been withdrawn.

The second is the actual behaviour of large global companies, even those operating in places like the US where ESG has been aggressively politicised. Tett suggests that they have concluded that it is more expensive to operate outside of ESG guidelines than within them:

(C)onsider events in California. Its legislature recently backed a bill that will require all large businesses which operate in the state to provide Scope 3 reporting by 2027. Many executives might hate this. But few global entities can afford to stay out of the state. So most will probably comply and impose it across the company, to avoid running different accounts in different regions — no matter what Washington (or West Virginia) says.

A third factor is the investment and innovation boom in clean energy. The former Bank of England governor Mark Carney reckons that there will be $1.8 trillion investment in green investment this year. Looking around Cambridge, Tett notes that the university is teeming with green research projects.

And the fourth factor is generational: Millennials and GenZ are more interested in, or concerned about environmental issues than older ones. Tett quotes a multi-country survey released last week by Newgate, which polled 12,000 people in 12 countries. It found

a significant increase in both awareness of (53 per cent aware, up from 46 per cent last year) and interest in ESG issues, with 67 per cent rating their interest at 7 or more out of 10, up 11 per cent since 2022”... Public awareness around that ESG term varies between countries, with the UK at the low end of the scale, while places such as the UAE or Singapore are near the top. But one common theme is that millennials and Gen-Z are far more aware of the climate issues than their parents and grandparents.

I saw similar data for the UK from Edelman last week, although I don’t have it to hand right now.

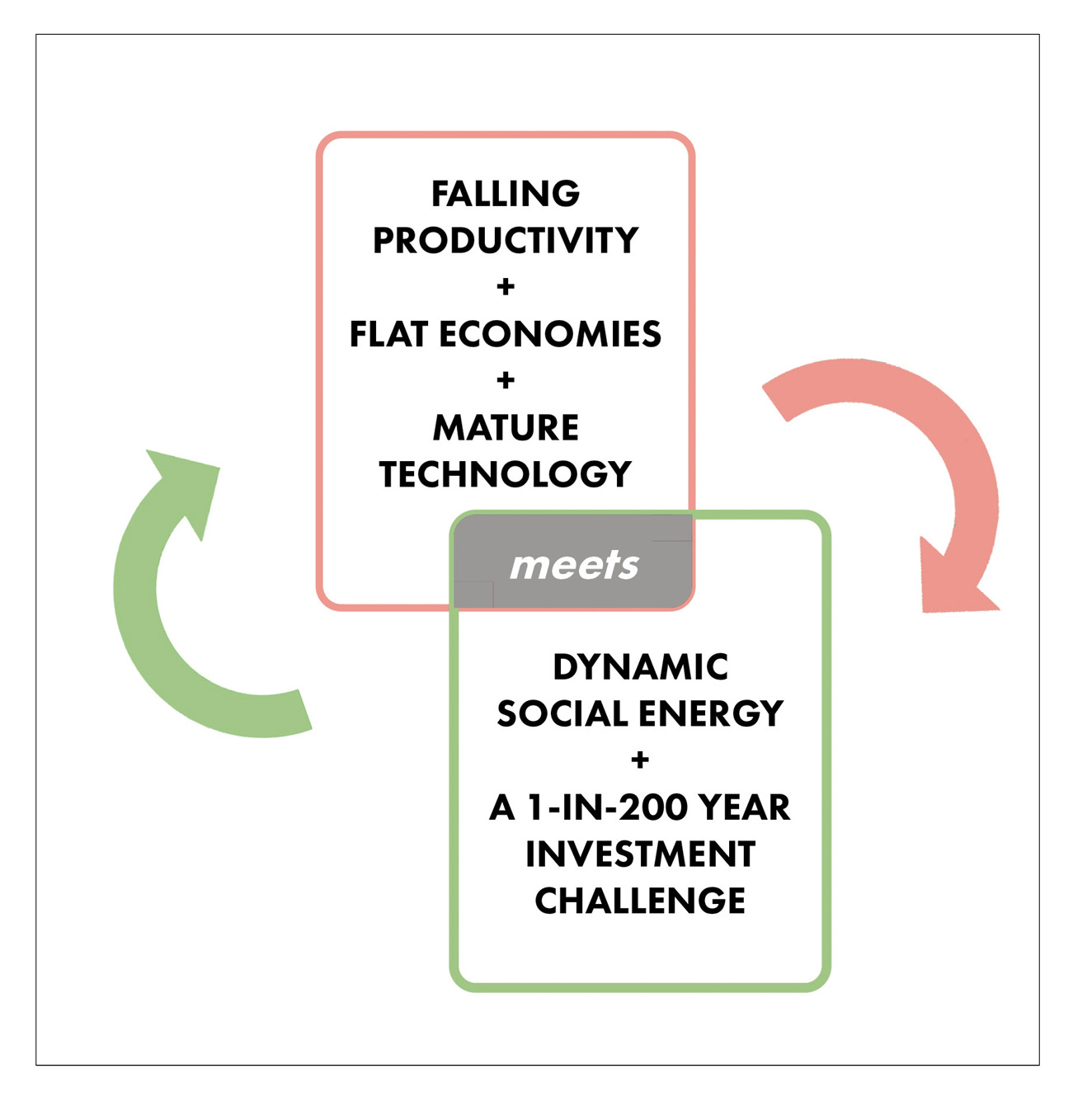

(Source: Curry and Bennett, ‘Better Business’)

This is not the greatest diagram in the world, but I came to a similar conclusion in a report I co-wrote a couple of years ago. When you look at the post-carbon transition through the lens of the big generational drivers of change (demographics, economics, technology, values, and resources), the combination that has the potential to be transformational is the connection between returns to green investment, and the cganging generational social values.

2: The geo-politics of global tech regimes

I haven’t got much time today (or this week) because I’m on the road for work, but I enjoyed this infographic on the different regimes that are used by the USA, China, and Europe to manage technology.

(Source: Anu Bradford, Digital Empires.)

It’s from her book, recently published by Oxford University Press, and I saw the diagram on the OUP blog.

There’s a little bit of commentary that goes with it:

Today, there are three dominant technology, economic, and regulatory powers that can be viewed as digital empires, each with the ambition and capability to shape the global digital order towards their interests and values. Each jurisdiction also holds a different vision for the digital economy, which is reflected in the regulatory models they have adopted.

So, Bradford argues, the USA model is largely market-driven, the Chinese model is largely state-driven, and the European model is rights-driven.

I think you can argue a little about whether the US model is just market-driven. Certainly prior to Lina Khan’s appointment to run the Federal Trade Commission, it was more like a market with government air cover. Indeed, in a longer extract from her book elsewhere, Bradford says as much.

Anyway, Bradford suggests that the different models have different geo-political strategies attached to them as well:

The US’ global influence today manifests through the dominance of its tech companies that exercise private power across the global digital sphere. China’s global influence can be traced to its infrastructure power, where Chinese firms—all with close ties to the Chinese state—are building critical digital network infrastructures in countries near and far. The EU exercises global influence primarily through regulatory power that entrenches European digital norms across the global marketplace.

Over the years, I’ve seen plenty of American tech commentators suggest that the European approach has prevented it from nurturing its digital success stories. But Bradford argues that it is better aligned with the interests of democratic governments in other parts of the world:

For many democratic countries, the U.S.’s market-driven regulatory model has proven to be too permissive, while China’s state-driven model is seen as too oppressive, leaving the EU’s rights-driven model the most attractive one to follow. As a result, a growing number of governments and individuals around the democratic world are now coalescing around a view that the EU’s regulatory model best enhances the public interest, checks corporate power, and preserves democratic structures of society, and are increasingly emulating that model as a result.

Effectively, this becomes a form of soft power.

Through its digital regulations, the EU shapes the global business practices of leading tech companies, which often extend these EU regulations across their global business operations in an effort to standardize their products and services worldwide—a phenomenon known as the “Brussels Effect.” The Brussels Effect describes the EU’s unilateral power to regulate the global marketplace. Because of the size and the attractiveness of the EU market, most large tech companies want to access that market, which requires them to comply with the European regulatory standards.

We’ve seen a trivial example of this market effect recently when Apple decided to comply with the EU’s decision to mandate USB-C connectors on devices. But obviously the GDPR regulations are a more significant example. Facebook (as it was then), Google, Apple and Microsoft all decided to comply, thereby globalising the standards.

Bradford expects the EU’s AI Act, due later this year, to have a similar effect:

Developers of AI systems who want to use European data to train algorithms empowering AI systems will be bound by the EU’s AI Act even beyond the EU’s borders. To escape EU’s regulatory constraints elsewhere, those developers would need to retrain their algorithms without European data, which can be unappealing as more extensive data often leads to better performance of the underlying models.

j2t#505

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague