18 February 2023. Generations | Valentine

Making a voice for future generations. // How Chaucer invented Valentine’s Day.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open. And—have a good weekend.

1: Making a voice for future generations

Sophie Howe has just stepped down as the first Commissioner for Future Generations in Wales, after six years. The post is term-limited, and the next Commissioner starts next month. BBC Futures used this as an opportunity to write about the whole idea of representing future generations, in a long article.

It’s also notable that on the issue of road-building—where Howe made her first high-profile intervention as Commissioner—the Welsh Government has just issued policy guidelines that start from a position that road-building is not necessarily a good thing.

(Disclosure—the issue of inter-generational fairness is central to the work of SOIF, where I do most of my futures work, and Sophie Howe will be collaborating with us on some projects.)

The BBC Futures article sprawls slightly, so I’ll try to pick out a few of the main points here, starting with the philosopher Ronan Krznaric, who wrote The Good Ancestor:

Climate change and the intergenerational issues around it are of course just one part of a much larger picture of long-term risks that face the world … says Roman Krznaric, a philosopher and author of The Good Ancestor . However, "the one thing we know about the climate crisis is that it has incredibly long-term impacts", he says. "That's the core of the intergenerational climate problem: we've colonised the future, we treat it as a dumping ground for ecological degradation, and technological risks, as if there was nobody there."

And although we know that billions of people will in fact inhabit the future, they are largely unrepresented in our political and policy-making systems. Krznaric again:

Our politics hasn't been designed to give those generations who will be impacted by our climate actions any kind of voice in the system.

(The Global Climate Strike in London on March 15, 2019. (Photo credit: Garry Knight/ Flickr )

As an aside here, this can also be seen as a problem of modernity, since one of its underlying assumptions has been of progress, and therefore that the future will be better for subsequent generations. The invention of nuclear weapons initially put paid to that idea, and the idea has since been challenged by by the climate emergency and the biodiversity crisis.

And latterly, even on its own terms, of economic and social progress. Significant numbers of people in the global North now believe that their children will be worse off than they were, which has been one of the drivers of the political crises caused by right-wing populism.

Back to the article: the idea of the Commissioner for Future Generations, enabled by Welsh government legislation, was designed in part to address this gap in our political systems.

The wellbeing of future generations act passed in 2015 by the Welsh government ( a devolved administration within the UK ) is one effort to address this. The act puts into statute a requirement for all public bodies – from health boards and local authorities to the Welsh government itself – to demonstrate how their decisions are meeting today's needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

The role of the Commissioner is to help public bodies work to achieve the seven long-term well-being goals set out in the Act,

including a prosperous Wales, a healthier Wales, a more equal Wales, a globally responsible Wales and a resilient Wales (this latter includes ecological resilience).

The Commissioner’s office can issue recommendations, and although these have no statutory power, public bodies do have to explain publicly their rationale when they ignore recommendations. Other countries are now considering following suit.

"You wouldn't think it was ground-breaking for a country to have a set of long-term goals," says Howe. "Wherever I go anywhere in the world and I talk about the future generations act, the general response is, 'Oh, my God, like, why doesn't every country have one?' Well, yes, exactly, why doesn't every country have one?"

In those countries that don’t have a formal role, the courts tend to be the arena where this plays out. There’s been a whole series of cases, across many different jurisdictions, that effectively ask this question about the obligations of the present to the future. In Germany, for example:

In 2021, a case brought by young environmental activists to Germany's constitutional court led to a ruling that the country's current emissions reductions were insufficient to protect future generations. The ruling noted that "one generation must not be allowed to consume large portions of the CO2 budget while bearing a relatively minor share of the reduction effort, if this would involve leaving subsequent generations with a drastic reduction burden and expose their lives to serious losses of freedom".

This goes to the heart of the argument about the rights of the future generations—because even younger generations already alive are likely to face a disproportionate burden:

"The people who are causing the climate crisis are not the ones who are going to be here to face the worst consequences," says Maria Reyes, a climate activist from Mexico with Fridays for Future Mapa (Most Affected People and Areas), speaking to Future Planet in 2021. "We have to recognise that the voices of young people, especially those from the most affected areas by the climate crisis, are valuable."

There are ways of articulating the views of future generations in the current political discourse, for example by using citizen’s assemblies informed by the native American idea of ‘seventh generation decision making’. (I’m a fan of a similar idea developed by Elise Boulding, of the ‘200-year present’, that asks people to look back and forwards three generations).

This native American idea has informed an interesting approach in Japan, called ‘future design’:

Local people are invited to discuss and draw up plans for the towns and cities where they live, with half representing residents in the present day and the other half asked to imagine themselves as residents from 2060. "It turns out the residents from 2060 systematically advocate far more transformative plans for their towns and cities , whether it's long-term investment in health care, or long-term action on the climate crisis," says Krznaric.

Krznaric also makes an important point about caring for future generations. It’s not so much about time, as about place:

He points to biologist and author Janine Benyus who writes about how other species have learned to survive and thrive by taking care of the place that will take care of their offspring. "I remember when I read that, suddenly, 'boom', it was like a revelation," says Krznaric. "It made me realise if you care about time and future generations, one of the best ways to do it is to care about place today.

From a futures point of view, one of the things that interests me here is that there are always some countries that are at the leading edge of policy-making ideas (Estonia, Finland, sometimes South Korea), and both Wales and Scotland seem to have joined this club since having their own devolved governments, partly because its in the interests of their governments to differentiate themselves from the mess that goes on in the UK’s central government, which is in serious need of innovation.

2: How Chaucer invented Valentine’s Day

(‘The Parliament of Birds’, Carl Wilhelm de Hamilton. 18th century, via Wikimedia)

While I’m publishing this on Saturday I’m trying to do some more cultural things, and what better, in that department, than the argument that the connection between Valentine’s Day and romance was an invention of Geoffrey Chaucer and other mediaeval writers.

The article, at The Conversation, is by Natalie Goodison, who teaches English at Durham. When younger she had visited the Italian church which keeps the head of St Valentine, and was told a story by the guide about Valentine being executed for conducting illegal marriages for then persecuted.

However, there’s no evidence for this. Valentine actually restored the sight of a Roman official’s daughter, and recruited many to Christianity as a result. There’s another St Valentine, but he is famous for curing a child, similarly winning converts as a result.

Enter Geoffrey Chaucer, centuries later. In his long poem Parliament of Fowles, published circa 1382, he has the birds gather to choose a mate (parliament meant a meeting before it meant an assembly of lawmakers). The date they meet on is St Valentine’s Day:

For this was on seynt Valentynes day,

Whan every foul cometh there to chese his make’ (309-10)

For this was on Saint Valentine’s Day

When every fowl comes to choose his mate.

The reference to Valentine’s clearly isn’t an accident, since he mentions it four times in the poem. This is the last reference:

Saynt Valentyne, that are ful hy on-lofte,

Thus syngen smale foules for thy sake:

Now welcome, somer…’ (683-85)

Saint Valentine, that are full lofty on high

Thus small fowls (birds) sing for thy sake.

Now welcome, summer…

Valentine and courtly love are also connected by a number of other writers in and around the same time:

Chaucer was not alone among his 14th-century contemporaries to do so. The English poet John Gower (d. 1408), the French poet Oton de Grandson (d. 1387) , and possibly the Valencian poet Pardo make references to Valentine’s Day and courtly love. By 1415 the French Duke of Orleans, imprisoned in the Tower of London, called his wife “Ma doulce Valentine gent” (my sweet gentle Valentine).

According to Jack Oruch (this via Wikipedia) Chaucer was likely to be "the original mythmaker in this instance."

The reference to summer in the Chaucer verse is relevant because of the date. February 14th seems a little early for birds to be choosing their mates, and there’s a suggestion that there was a St Valentine of Genoa who had a feast day on May 2nd, by which time spring was close to turning to summer. (Chaucer had travelled to Genoa).

However, there’s also a tradition that the middle of February marked the end of winter and the beginning of spring.

(A)ccording to traditional medieval calendars, spring began with the appearance of the Pisces star sign, which occurred on February 15. Other traditional calendars regard February as the first month of spring. Several medieval calendars state that birds begin to sing on February 12.

That was interesting to me because of an idea I read recently about notions of the calendar in pre-industrial times. (I think it was in John Higgs’ book Watling Street but of course can’t lay my hands on it right now). This suggested that in pre-industrial England the calendar was divided into approximately six week chunks, with the solstices and the equinoxes marking the quarters, and feasts marking the mid-points of each of these. So it’s possible that mid February marked the mid-point between the winter solstice and the spring equinox.

(Manuscript of Parliament of Fowles, British Library)

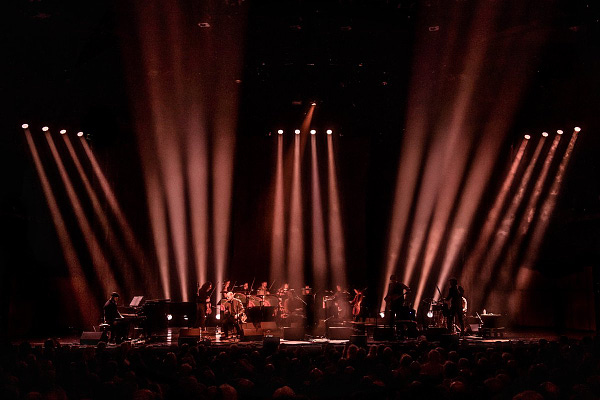

Other writing: Music

I was away at Glasgow’s Celtic Connections festival recently—probably the biggest Celtic music festival in the world now—and am writing some articles about artists and concerts at the folk music site Salut Live!. The first one, about the violin player Duncan Chisholm, was published earlier this week. Here’s an extract:

Chisholm is now in his 50s, but he has been influential in Scottish folk music since his early 20s. He was a co-founder in the early 1990s of Wolfstone, which opened up Scottish traditional music to electric instruments...

What’s distinctive about (his work) is that he has taken the airs, jigs, and reels that he grew up with, and which make up so much of Scottish traditional music, and has transformed them into a modern sound that works for a 21st century audience, but without losing the thread to the music’s traditional roots. Black Cuillin, which Chisholm describes as his “most ambitious” work yet, does this through a combination of a big cinematic sound, electric reinforcement on some tracks, and some subtle electronic effects.

j2t#426

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague