18 April 2025. Home | Haiku

The philosophy of the home // The frog, the pond, and the inventor of the haiku. [J2T #636]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish a couple of times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

It is Easter, so I’m doing a couple of literary-related things today. The piece on haiku is to mark that it was International Haiku Day yesterday, and it’s a revised and expanded version of a shorter piece about Basho that was posted on my blog Around the Edges.

1: The philosophy of the home

Emanuel’s Coccia’s starting point in The Philosophy of the Home is that the history of philosophy, going all the way back to the Ancient Greeks, has been more about the public life of the city. In that process the public life represented by the home has been overlooked.

And not just in philosophy, he says, early on:

The home has been the subject of theoretical neglect; it's as if, over time, it had been transformed through its own will into a strange kind of machine that has to gather everything we cannot talk about in public or need to forget. [10]

He sets out to fill this gap. For my part I don’t know enough of the history of philosophy to know if he is overclaiming or not, so I’ll have to take all of this on trust.

It becomes clear a little later on that one of the reasons that Coccia might be interested in the philosophy of the home is that he has lived in a lot of them—30 or so, by his calculation, because of the peripatetic life of the academic. (Even so this seems high to me: there must have been some element of choice in these life decisions? If so, he doesn’t reflect on it.)

But ‘homes’, he argues, don’t exist, because they are a process, not a place. What does exist is home-making. The home is a location for the ‘I’, by which he means, literally, ourselves, the person we refer to as ‘I’:

A home is the ‘I', though not as a private and singular fact... it is the threshold at which the subject becomes reality in the world, and the world begins to have a single unmistakable face. [25]

He starts in the bathroom, which along with the kitchen is the most technically complex space in the house (all that plumbing). Living in an east Berlin apartment at around the turn of the century the shared toilet is still on the landing, because of an old city ordinance that required them to have external ventilation.

(East Berlin apartyment blocks. Photo: Ali Eminov/ flickr. CC BY-NC 2.0.)

The shower in this house, a later addition, has been wedged into the kitchen, which creates a clash between a private space and a public area. This leads to a reflection on the essentially private nature of the bathroom, the most ‘I’ of the rooms in the home, the room that is most likely to be lockable, the only room in the house that is dedicated to one set of functions.

A house consists mainly of air and stone; but the bathroom is, by definition, a place in which liquids dominate, whether they are toxic wastes to be discharged or liquids that revive and refresh. [48-49]

Some of the chapters here stray some way from the topic, if I’m honest. It’s interesting, perhaps, that Coccia is a twin, but the chapter that starts with this has only the most tenuous connection to the subject. Similarly, a chapter on writing in which the act and processes of writing eventually becomes some kind of metaphor for our relationship with the home seems, at best, contrived.

All the same, in these flights there are also sometimes worthwhile insights. In a chapter on social media, for example, he contrasts the familial and traditional structures of the home with the galleries of friends offered by social media platforms, before riffing on a genuinely interesting idea, new to me, from Ernst Kapp, who was writing in the 19th century.

Traditional machines are based on the imitation of a physical organism. In contrast, says Coccia, new machines are based on an imitation of the psyche. This goes back to photography and the cinema, but is exemplified by mobile phone:

[W]hile traditional machines made it possible for human bodies themselves to exert a subjective force externally and direct it towards an objective, the new machines make the soul exist outside us, they turn the life of the psyche into a feature that can exist not only in the human anatomy but in any object, and which can come alive at any moment. [117]

Some of this is reminiscent of one of the McLuhans’ technology tetrads in The Laws of Media. One of the four laws is that a technology always extends a human capability. The idea that this change goes back to the late 19th century allows Coccia to make a striking connection with these earlier audio-visual technologies and the rise of modernism in the first part of the 20th:

For almost a century we have required literature and the pictorial and plastic arts to invent and bring visibility to the structure of our 'I':... James Joyce's Ulysses, Virginia Woolf's Mrs Dalloway, Marcel Proust's In Search of Lost Time, and Jackson Pollock's action painting allowed the ‘I' to be structured in this way. [118]

If the home is a lacuna in philosophy, so is the bed—or maybe, more precisely, is sleep. Apparently Karl Löwith “once wrote that philosophy has never worried itself about the fact that all people spend at least a third of their days asleep.” [130] For Coccia, the moment that is of interest here is the moment of reawakening, and one of these passages gives you a sense of his style:

Reawakening is not the transition from absence of perception to presence of perception, but the intuition of a kind of autonomous, general consciousness of the world which has always been there, which we sometimes manage to appropriate and make our own. The world is already vivid, actively conscious. [133]

So one of the ways to think about this book is as if it is a concept album, with a broad overall theme connecting together a long series of improvisatory riffs. Sometimes those riffs spark something in the reader, and sometimes you can just let the tune wash past you. The translation from the Italian is by Richard Dixon.

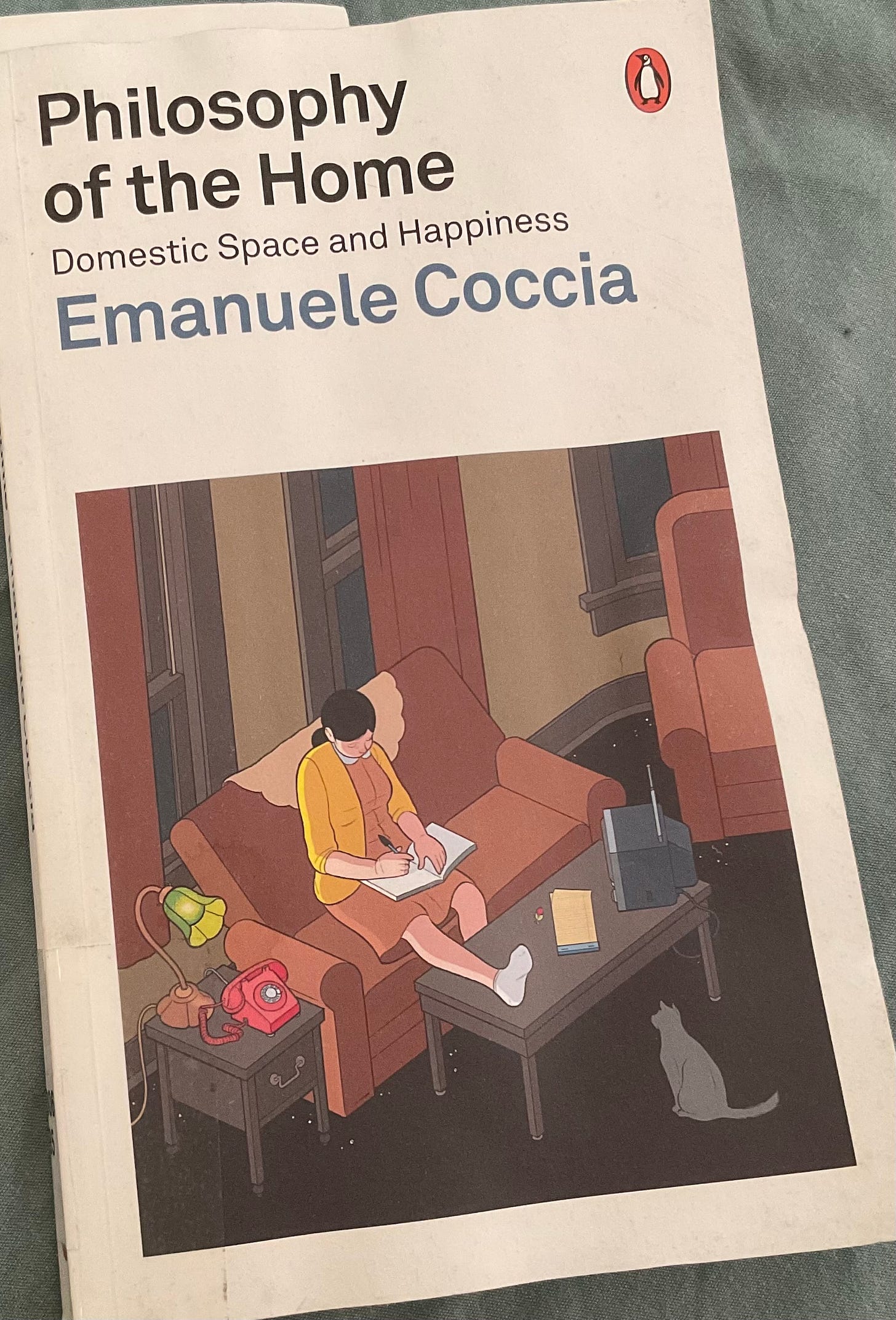

(Photo: Andrew Curry. CC BY-NC 4.0)

Coccia riffs, certainly, on the idea of gardens, identifying them as being related to the point when people stopped being nomadic and started to grow plants and crops. Because that also meant that people stopped being mobile and a home became a place.

And when he finally gets back into the kitchen again, he suggests that it connects the home not to the city, but to the whole world. This is a bravura passage that’s characteristic of Coccia’s style:

In the kitchen, every home stops being a closed, proprietary human space. Pigs, chickens, oxen, corn, cocoa, coffee, maize, hazelnuts, pears, apples, bananas, lettuce: the most far-flung lives meet at this single point in the world to replace atom for atom the material of our body. It's in this space that we admit there is nothing human about us. [167]

And, says Coccia, the kitchen is the secret to reclaiming the home for philosophy.

If urban space is considered from the viewpoint of the kitchen, we are forced to admit that cities are much vaster than we imagine: all non-human living beings that we generally exclude must form part of it. [168]

He connects this to a similar trend in architecture, which he credits to William Cronon and the landscape architects Carolyn Steel and Dorothee Imbert. This also reminded me of Herbert Giradet’s vision of our future city as being an ‘econopolis’ rather than our current ‘petropolis’.

The final chapters in this short book—biggish type, widish line spacing—build on this fusion of home and planet. At once “we are at home everywhere”—everywhere, pretty much, has been inhabited by humans—and at the same time “home itself has become a planet.” Which leads to a question:

How do we live in a home that is as large as the whole planet? [179]

And he sees the home of the future as being a kind of philosopher’s stone, capable of transmutation and transformation:

If the home of the past was a machine that made distinctions, in the future it ought to become the collective discipline of blending... Homes will be the kitchens of the planet: inside them the Earth will find a new flavour. [180]

2: The frog, the pond, and the inventor of the haiku

The 17th century Japanese poet Basho invented the haiku, and his book Narrow Road to the Deep North is about a 1,500-mile walk up one side of Japan, across, and down the other side, towards the end of the 17th century. He was 45 at the time, but not ageing well, and he was mostly accompanied by his ‘disciple’ Sora. The roads were not good and there were potential dangers.

His walk was intended to acknowledge his literary influences, and Basho prepared for it by selling his house. There’s some evidence that he didn’t expect to survive the journey.

(Basho, by Hokusai. Public domain)

Basho was a pen-name adopted in mid-life, from a banana tree that he was given as a gift for his garden. He turned the haiku (or hokku, as it was then known) into a serious literary form. My copy of the book came from the library, and may not be the best translation, but the translator still manages to say quite a lot about the Japanese-ness of the haiku, and the difficulties of translating it.

I was started on this modest literary journey by reading a quote from The Narrow Road included as an epigraph to a book by Rebecca Solnit about travelling across Ireland:

Every day is a journey, and the journey itself is home.

The haiku, of course, is a poem with five syllables in the first line; seven in the second line; and five in the third line. When I mentioned Basho to my son Peter he recalled Basho’s most famous haiku, about a frog—probably the most famous poem in Japanese—and found a page of multiple translations.

This is the Japanese original with a more or less literal translation by Robert Aitken, who had curated the page, to the right:

Furu ike ya Old pond!kawazu tobikomu frog jumps inmizu no oto water’s soundAs he explains:

The first line is simply “The old pond.” This sets the scene — a large, perhaps overgrown lily pond in a public garden somewhere. We may imagine that the edges are mossy, and probably a little broken down. With the frog as our clue, we guess that it is twilight in late spring... “Old” is a cue word of another sort. For a poet such as Bashô, an evening beside a mossy pond evoked the ancient.

In Dorothy Britton’s introduction to the edition of The Narrow Road, she translates it like this:

Listen! A frog

Jumping into the stillness

Of an ancient pond!

Aitken’s collection of translations includes this highly economical version by James Kirkup, the poet and translator who knew Japan well:

pond

frog

plop!

Aitken also discusses both the specifics of the ‘frog’ haiku and the wider form in his discussion:

Ya is a cutting word that separates and yet joins the expressions before and after. It is punctuation that marks a transition — a particle of anticipation... In the original, the words of the second and third parts build steadily to the final word oto. This has penetrating impact — “the frog jumps in water’s sound.” Haiku poets commonly play with their base of three parts, running the meaning past the end of one segment into the next.

The haiku is more or less untranslatable into English, and this is not only because of the economy of the form. The translator of this editon of The Narrow Road, Dorothy Britton, explains that rhyme doesn’t really work in Japanese; that haiku is supposed to be ‘seasonal’, as in referring to the seasons, and that there’s a whole lexicon here to help the poet. The third point is that they are so compressed that they are always capable of ambiguity, and that this ambiguity is amplified by the large number of homonyms in Japanese.

She gives an example of this from the haiku that Basho writes to conclude The Narrow Road. She translates it like this:

Sadly, I part from you

Like a clam torn from its shell

I go, and autumn too.

But in the Japanese, there’s also a much more mundane version of this, where the word ‘clam’ stands in as synecdoche for Futami, a town that was famous for its clams, so all that it is saying is

Now that it is autumnI leave you for FutamiFamous for its clams.

Apparently both work just fine as translations.

And before I finish on Basho, I also learned that the 5-7-5 syllable form of the haiku is actually a form that has been detached from a slightly longer tradition form, the tanka, which was a five line verse with a 5-7-5-7-7 pattern.

Part of Basho’s journey, and book, is about paying homage to older Japanese poets, and there’s a sequence in the book that acknowledges a poet called Saigyō, in a village called Ashino. Here’s Saigyō's tanka:

On that roadside leaWhere pure crystal waters flowedGrew a willow tree;For a little while I stayedThere and rested in its shade.

Basho walked 10 miles a day, on average, in straw sandals. It was probably more because there are a few places where he stayed for a few days. There are a few places where they hire horses because they are tired or dispirited. Every so often, the text throws up questions, at least for this reader, about 17th century Japan: the gate keepers who seem to have the authority to turn them back, for example.

It wasn’t an easy walk—there’s a bit of mountain where they need to hire a guide, who travels with a stout stick and a sword, and another climb to the top of a mountain where they walk across ice and snow before sleeping at the top until being wakened by the dawn.

And—not spoilers—he did get home again. Happily, his disciples provided him with a house, where he worked on the manuscript for three years, finishing it shortly before his death in 1694. It was published in 1702.

j2t#636

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.