17 September 2021. Competence | Clearances

Competence is better than literacy; Sorley MacLean’s great poem, Hallaig

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Service is slightly disrupted while I’m away. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: Competence is better than literacy

One of my concerns about the idea of “futures literacy”—at least in the ways that I’ve had it explained to me—is that is basically unsystemic. It invites us as individuals to become futures-literate without really helping to create the conditions in which systems might become futures-literate.

It’s a bit like—say—helping people improve their carbon footprints while doing nothing about the carbon-intensive and locked-in behaviours of the energy or transport or construction sectors.

So I was interested to see a post by Rob Miller (noted by John Naughton) that underlined the importance of competence rather than literacy. To be clear, Rob Miller isn’t writing about futures—he’s making a much wider point—but maybe the same principles apply:

Literacy is about familiarity: the ease with which you can navigate a world, how au fait you are with its codes and conventions, its implicit expectations. But literacy is fundamentally passive: “literacy kind of assumes that you’re the reader or viewer of images,” (Taiwan’s Digital Minister Audrey) Tang says. “Competence means you’re the producer.” Competence involves solving real-world problems and navigating uncertainty yourself, taking in and synthesising different points of view; literacy often means solving artificial problems put in place by bureaucracies and corporate structures that demand conformity to a single view of reality.

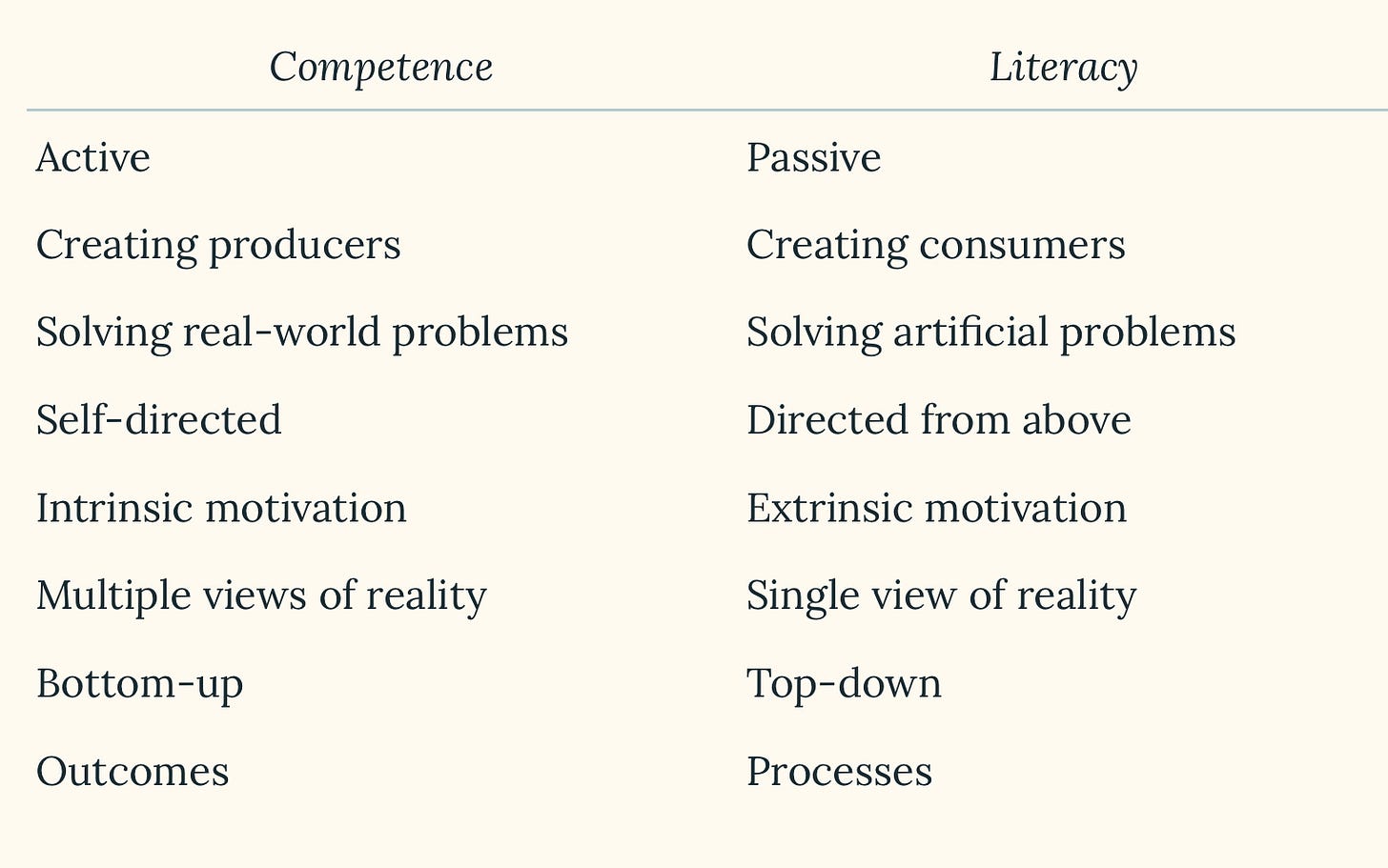

He has a helpful table that he’s put together that separates out the differences between the two approaches:

(Source: Rob Miller)

As he says,

If literacy is about familiarity with a script, what happens when that script changes? The merely literate are lost for words; the competent are able to improvise. Organisations that build only literacy are fragile when times are bad, and fail to innovate when times are good.

Miller is more interested in the way that organisations operate, and he suggests three principles that enable organisations to promote competence over literacy.

The destination, not the journey. They measure success through outcomes, rather than by people’s correctness in adhering to a process...

Co-learning, not exam-setting. ... (E)mployees take charge, and leaders facilitate a collaborative process of discovery.

Bottom-up iteration and evolution. They don’t set processes in stone, but instead continually evolve them.

I’m sure the advocates of futures literacy would be quick to say that they agree with all of this. It would just be nice to see some more systemic language in the way the concept is explained.

#2: Sorley MacLean’s great poem, Hallaig

(Image of OS map: Andrew Curry)

You can’t visit the Highlands or islands of Scotland without being conscious of the clearances, the brutal process by which the land was cleared of people between the 1840s and the 1880s to make way for sheep, and later, deer.

The historiography of all of this has become more complicated recently, but the fact is that people used to lived here in greater numbers than they do now and a lot of people did not leave voluntarily. As Andrew Greig reminds us in his book At the Loch of the Green Corrie, the idea of “the empty glen” is a a human construct, not a natural landscape.

Perhaps the greatest poem on this subject is Sorley MacLean’s ‘Hallaig,’ written about a village on his native island of Raasay that was cleared in the 1850s. Most of the stone from the cottages was used—of course—to construct a huge sheep tank, but you can still find the ruins of the cottages that were there, and the place is still to be seen on the map.

(Photo: The stones of Hallaig, used to build a sheep pen. Vincent van Zeijst, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Indeed, the poet Sheenagh Pugh rates ‘Hallaig’ as “the greatest poem written in these islands in the 20th century”, while acknowledging that this may be a minority view.

This is the poem, in a translation from the Gaelic by Seamus Heaney:

Hallaig

Time, the deer, is in Hallaig Wood

There's a board nailed across the window

I looked through to see the west

And my love is a birch forever

By Hallaig Stream, at her tryst

Between Inver and Milk Hollow,

somewhere around Baile-chuirn,

A flickering birch, a hazel,

A trim, straight sapling rowan.

In Screapadal, where my people

Hail from, the seed and breed

Of Hector Mor and Norman

By the banks of the stream are a wood.

To-night the pine-cocks crowing

On Cnoc an Ra, there above,

And the trees standing tall in moonlight -

They are not the wood I love.

I will wait for the birches to move,

The wood to come up past the cairn

Until it has veiled the mountain

Down from Beinn na Lice in shade.

If it doesn't, I'll go to Hallaig,

To the sabbath of the dead,

Down to where each departed

Generation has gathered.

Hallaig is where they survive,

All the MacLeans and MacLeads

Who were there in the time of Mac Gille Chaluim:

The dead have been seen alive,

The men at their length on the grass

At the gable of every house,

The girls a wood of birch trees

Standing tall, with their heads bowed.

Between The Leac and Fearns

The road is plush with moss

And the girls in a noiseless procession

Going to Clachan as always

And coming boack from Clachan

And Suisnish, their land of the living,

Still lightsome and unheartbroken,

Their stories only beginning.

From Fearns Burn to the raised beach

Showing clear in the shrouded hills

There are only girls congregating,

Endlessly walking along

Back through the gloaming to Hallaig

Through the vivid speechless air,

Pouring down the steep slopes,

Their laughter misting my ear

And their beauty a glaze on my heart.

Then as the kyles go dim

And the sun sets behind Dun Cana

Love's loaded gun will take aim.

It will bring down the lightheaded deer

As he sniffs the grass round the wallsteads

And his eye will freeze: while I live,

His blood won't be traced in the woods.

--

There’s a fine setting of the first two verses by the innovative Canadian/Scots musician Martyn Bennett, who died far too young of cancer. The reading here is by Sorley Maclean. The video below is by Neil Kempsall, via Bella Caledonia:

j2t#169

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.