17 November 2021. Whales | Wealth

Forget trees. Whales are vast carbon sinks | The asset boom is getting out of hand.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: Forget trees. Whales are vast carbon sinks.

I hadn’t realised that whales were a carbon sink. And perhaps as surprising, the research that discusses this has been published by the International Monetary Fund, which is perhaps as good a signal as anything else that our large traditional institutions are changing.

One whale, it turns out, is worth thousands of trees.

As the article’s authors note of many climate strategies:

Many proposed solutions to global warming, such as capturing carbon directly from the air and burying it deep in the earth, are complex, untested, and expensive. What if there were a low-tech solution to this problem that not only is effective and economical, but also has a successful funding model?

Whales, on the other hand, are a ‘no tech strategy’:

Marine biologists have recently discovered that whales—especially the great whales—play a significant role in capturing carbon from the atmosphere (Roman and others 2014). And international organizations have implemented programs such as Reducing Emissions from Degradation and Deforestation (REDD) that fund the preservation of carbon-capturing ecosystems.

And frankly, the numbers are quite surprising.

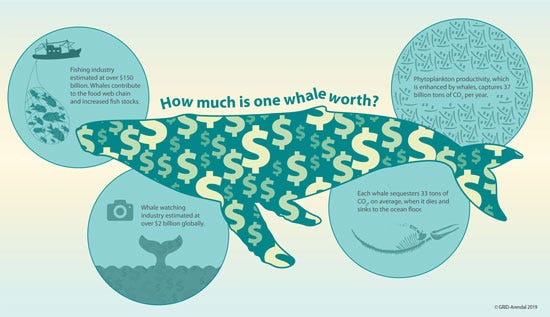

Whales accumulate carbon in their bodies during their long lives. When they die, they sink to the bottom of the ocean; each great whale sequesters 33 tons of CO2 on average, taking that carbon out of the atmosphere for centuries. A tree, meanwhile, absorbs only up to 48 pounds of CO2 a year.

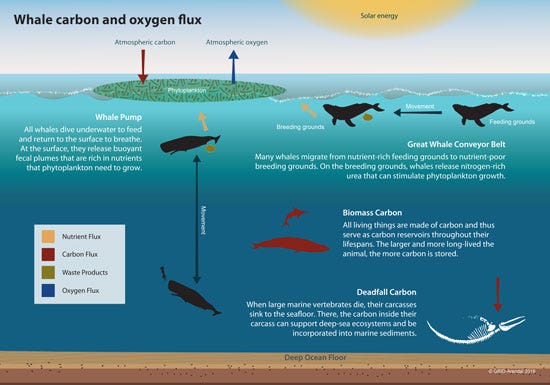

But the story is more interesting than that, because of the way that whales interact with their ecosystems. It gets a little technical at this point, but wherever whales are found there are also populations of phytoplankton. They’re tiny, but they also absorb carbon—and pump out oxygen.

These microscopic creatures not only contribute at least 50 percent of all oxygen to our atmosphere, they do so by capturing about 37 billion metric tons of CO2, an estimated 40 percent of all CO2 produced. To put things in perspective, we calculate that this is equivalent to the amount of CO2 captured by 1.70 trillion trees—four Amazon forests’ worth—or 70 times the amount absorbed by all the trees in the US Redwood National and State Parks each year.

(Source: via IMF)

And whales, it turns out, are good for phytoplankton—there’s a kind of multiplier effect at work.

(W)hales’ waste products contain exactly the substances—notably iron and nitrogen—phytoplankton need to grow. Whales bring minerals up to the ocean surface through their vertical movement, called the “whale pump,” and through their migration across oceans, called the “whale conveyor belt.” Preliminary modeling and estimates indicate that this fertilizing activity adds significantly to phytoplankton growth in the areas whales frequent.

So obviously it’s a shame that humans devoted so much hard work to wiping out the planet’s whale populations in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Rebuilding those populations would be a good idea in the face of the climate emergency. But even small effects on phytoplankton have decent impacts on carbon:

At a minimum, even a 1 percent increase in phytoplankton productivity thanks to whale activity would capture hundreds of millions of tons of additional CO2 a year, equivalent to the sudden appearance of 2 billion mature trees. Imagine the impact over the average lifespan of a whale, more than 60 years.

So why is the IMF interested in whales? Because all these environmental benefits mean that whales are effectively an international public good, but it is often the fate of public goods that they are undervalued. So the IMF is trying to work out how to value whales properly (because even if they’re not much hunted these days, except perhaps by Japanese ‘research’ vessels, they are still at risk in lots of ways. And their calculation, spelt out in the image here, is that the average great whale is worth more than $2 million.

(Source: via IMF)

If whales were enabled to return to their previous numbers, the IMF researchers reckon the benefit is $13 per person per year. Put like that, it’s not much money. And multilateral institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank already have financial mechanisms in place that could make sure that the public good represented by the world’s whales is valued properly and protected properly:

Coordinating the economics of whale protection must rise to the top of the global community’s climate agenda... International institutions and governments, however, must also exert their influence to bring about a new mindset—an approach that recognizes and implements a holistic approach toward our own survival, which involves living within the bounds of the natural world. Whales are not a human solution—these great creatures having inherent value of their own and the right to live—but this new mindset recognizes and values their integral place in a sustainable ocean and planet... The “earth-tech” strategy of supporting whales’ return to their previous abundance in the oceans would significantly benefit not only life in the oceans but also life on land, including our own.

And hurrah to all of that, of course. But this definitely isn’t the IMF I studied in undergraduate economics a few decades ago.

H/t Adam Tooze

#2: The asset boom is getting out of hand

A short piece by Richard Murphy points towards a longer piece of research by the McKinsey Global Institute on changes in global wealth between 2000 and 2020.

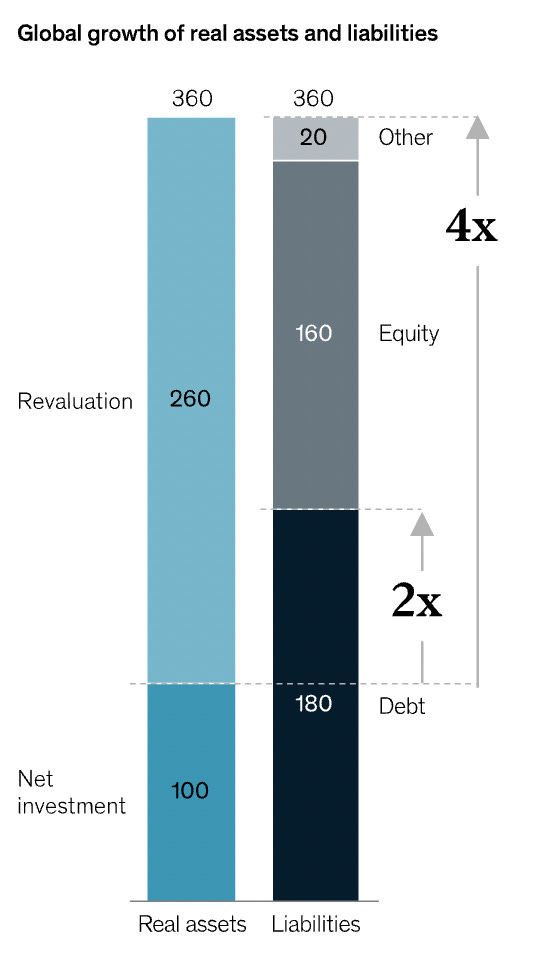

This is the key chart, and what it says is that we are living in a world in which gains in wealth have come almost entirely from increases in the value of assets, mostly land and property.

And that a lot of debt is going to paying returns to the holders of those assets.

(Source: McKinsey Global Institute)

This is probably the result of a decade and a half of quantitative easing by central banks to keep the post financial crash economy afloat, without any corresponding measures to channel that money away from speculative finance.

Murphy also pulls out a second chart that shows how much of those assets are accounted for by real estate—more than two-thirds.

(Source: McKinsey Global Institute)

As Murphy notes:

It is as if feudalism had not ended: this is a world where land backs wealth. And older generations are using that as the opportunity to leverage returns, whether from sale prices or rents, from younger generations.

Marxist economists sometimes talk about ‘fictitious capital’, which means capital that isn’t involved in any form of production. Well, this is what a society that’s built on fictitious capital looks like. This might also be one of the reasons for the endless decline in productivity.

McKinsey summarises the research like this:

- The market value of the global balance sheet tripled in the first two decades of this century

- Real estate makes up two-thirds of global real assets or net worth

- Asset values are now nearly 50 percent higher than the long-run average relative to income

- Financial assets and liabilities also grew faster than GDP, vastly exceeding net investment

- Several scenarios are possible, with an imperative to deploy wealth more productively for critical investment needs.

The last of these is McKinsey code for ‘we need to stop spending money on real estate and invest in more productive assets’.

Murphy’s takeaway: the case for a wealth tax gets stronger all the time—and probably for a land tax as well.

j2t#209

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.