17 June 2024. Change | Cars

Creating paths for change—Jim Ewing’s dialogue maps // China is the clear leader in the global electric vehicle market [#582]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Creating paths for change—Jim Ewing’s dialogue maps

I’ve been looking forward to the publication of Jim Ewing’s book Braving Uncertainty (Triarchy, 2024) ever since Graham Leicester referenced his work in a few pages of his book Transformative Innovation. Ewing was, until his death in 2014, a member of the group of practitioners convened by Graham at the International Futures Forum in Scotland.

The manuscript for Braving Uncertainty was drafted by Ewing before his death and for that reason we can think of this as his “legacy” book, even if publication has been delayed for a decade.

Ewing explains his own personal journey in an introductory chapter. He was an engineer who grew to be more interested in helping organisations, and people, make change. Along the way he picked up and synthesised various intellectual influences that helped him to shape the change-making tools that he developed.

I’m going to discuss one of those in more detail to give a flavour of his approach, but this is at least as much a “doing” book as a “reading” book. There are five tools here, and Ewing makes the connections between them as he goes. They also have reasonably catchy names: The Insight Cycle; Stucco; Implemento (which generates options); Impacto (which gets to a decision); and TransforMAP.

I could describe all five, but I think it’s more useful to understand Jim Ewing’s practice and thinking by focusing on the first of these.

At the heart of this, he is trying to help organisations and individuals to change their story. Making sense of our lives, individually and collectively, “is a fundamental human necessity.” As we encounter turbulence and change, we need to be able to incorporate it “into our existing narratives”:

This is the inner work of change - adapting the story we tell ourselves to make sense of who we are, where we are going and how the world is going to support us in the journey. Satisfactory changes cause us to grow, to use more of ourselves, to extend our being into added dimensions. Unsatisfying changes are frauds, because we just repeat the same old life patterns in a different guise (pp17-18).

The stories we carry are likely to be a mixture of the upbeat and positive and the downbeat and discouraging. When a shock happens, our temptation is usually to “fix” the cover story, to maintain “an illusion of predictability and control.” But this also disconnects us from the deeper truths that the shock might open us to.

It’s also worth saying something about Ewing’s philosophy of working with organisations going through change, because he characterises a hierarchy of help.

The first is problem-solving: a tax accountant can help you put the right numbers in the right boxes. When upheaval strikes, however, “fast answers” are like “fast food”, because we’re in a world where the outcomes are not known at the outset.

Ewing characterises this second level as “transformative enquiry”, and advice is not helpful here. (He recommends writing down the advice you might be tempted to give in a private notebook.) In this level,

The good news is we don't have to be experts at all. We just pursue artful conversations and guide others into helpful frameworks of thinking (p29).

The third level is presence: “our client is deep in the muddle.” And that means we need to attend, in both senses of the word:

Platitudes and feel-good slogans are completely unhelpful... There is nothing to be done, so we show up as a wise and thoughtful witness. We just sit in the exquisite moments when someone confronts their core. Being a transformative presence is the highest form of our art (p29-30).

The first of these tools, the Insight Cycle, the core of Ewing’s approach, is designed to set the ground by helping individuals and organisations create a map of where they are and where they want to be.

On the face of it, the Insight Cycle is a simple enough device. It has four nodes and two axes. The nodes—compass points on a circle—are Situation (at the east), Mind, Behaviour and Influence. The first axis, ‘Doing’, runs east-west; the second axis, ‘Being’, runs north south.

(The Insight Cycle. Jim Ewing (2024), Braving Uncertainty. The symbols—glyphs—are visual metaphors.)

The illustration for this “is a simple drawing, in the effortless style of cave drawing and hieroglyphics.” I immediately warmed to the roughness of this (the designer isn’t credited) in that they feel half-finished, rather than the crisp, tidy—and closed—geometric shapes seen in much consulting work.

Sketching this out. Ewing underlines that the language used to describe the nodes and axes should be neutral and non-judgmental. It is what it is.

Situation—the easterly node—is the collection of “physical conditions, outcomes, results, performance mechanisms... which we use to define how things stand for us in the world.”

Behaviour, at the west, is “our doings and not doings, our actions, steps and moves... business processes, procedures and systems.” This is

“not the system design, but how the system or procedure or team actually measurably behaves (p39).

Obviously we can think of many organisations that could have done with some candour about their actual behaviour before catastrophe struck, although they also seem like the last organisations that would have invited Jim Ewing into the room.

The “Doing” axis runs between these:

We find ourselves in a situation and we respond with behaviour designed to improve our conditions.

Most of the noise of organisations—when you read their reports or listen to their chief executives—are full of “doing”:

I had a witty colleague years ago who said that her company was full of 'human doings. I think she was talking about an organisation with a huge bias to being busy and putting points on the scoreboard, driven to hurry up and deliver results without a lot of so-called 'navel gazing, which another colourful human doing I know likes to call the process of thinking (p40).

Onto the other axis. Influence is at the north, which connects Behaviour back to Situation:

It is a transformer which takes our behaviour and acts on it in some way to convert it into a changed situation in the East (p41).

But there is a cautionary note here:

Influence is a complex system of physical creation which runs constantly and which is way beyond anyone's comprehension, much less control (p41).

The south of the circle is Mind. This is “a transformer... which processes situations into actions.” It holds

my beliefs, assumptions, mental models, experience, dreams and aspirations, intentions, passions and urges. Also my biases and prejudices... For an organisation, the domain of 'Mind' holds strategy, mission, brand, policies, rules and regulations, both spoken and unspoken. The so-called glass ceiling, above which some classes of people may not be promoted, is a product of the unspoken, organisational 'Mind’ (p43).

Ewing suggests that Mind has three components—a version of heart (emotional), head (thinking), and hands and feet (physical)—and these are often out of sync with each other.

Between these last two runs the ‘Being’ axis:

Engaging this axis calls on our curiosity, patience, humility, and a willingness to endure uncertainty and ambiguity. On this axis be dragons (p44).

This is not meant to be an easy diagram, and nor is the journey around it. There are tensions and conflicts. It doesn’t have a neat ending: “The game never stops... The Cycle cycles.”

One of the things that makes the work harder, especially in organisations, is that different parts of the system only look at one element within it:

A financial analyst does just that by describing company 'Situation' measured solely in profit and loss. The Personnel department reports on employee attitudes and mood—measures of 'Mind’. The Marketing team tracks changes in the 'Influence called consumer expectations. Production managers offer a history of the operation of the order entry process, a story of pure 'Behaviour’. None of these domains, taken by itself, is very interesting (p48).

I’ve dwelt on this to convey Ewing’s worldview. The book comes with stories and examples. Each of the four nodes has an additional tool attached to it, to amplify discourse and deepen understanding. Stucco (sic) helps with Situation; Implemento with Behaviour; Impacto helps with Influence; and TransformMAP—I so wanted this to be called Transformo—with Mind. As someone who does some of this work sometimes, these are clearly rich dialogue tools.

It’s not a long book, but Ewing has, I think, distilled a lifetime of practice into it. As he says near the end, “These maps have been decades in the making.”

In a section near the end, he acknowledges some intellectual debts. Some come from grief therapists such as Elizabeth Kubler-Ross and Stanley Keleman; some from psychiatrists and Jungian psychology: Roger Gould, Hal and Sidra Stone; Roberto Assagioli; Piero Ferruci. Some of these names were new to me.

In these decades of map-making, Jim Ewing crafted these different voices into a humane set of practices to help organisations work with change. You get the sense from the book that he would have been a fabulous companion on that journey.

Braving Uncertainty, by Jim Ewing, is published in July by Triarchy Press, but copies are available before then. EU customers are advised to buy the ebook, because Brexit. There’s a pdf of the introductory chapter here.

2: China is the clear leader in the global electric vehicle market

There have been a couple of short pieces recently on the status of China’s electric vehicle industry: large, growing, and with rapidly falling economies of scale and scope. One of these, by Kevin Williams for the site Inside EVs, was headlined,

I Went To China And Drove A Dozen Electric Cars. Western Automakers Are Cooked.

Well, of course, some of that language might be clickbait, and it plays into a familiar discourse about China’s “industrial threat” but if we park that for a moment it’s worth just recording what the two pieces say about the status of China’s EV industry.

And to be fair to Inside EVs’ headline, part of Williams’ intentions in his piece is to respond to some of the views about China’s EV sector that have been expressed to him by American auto executives:

Many of them believe China’s industries are not sustainable, and the cars it wants to foist on the public are cut-rate spyware machines designed to murder American citizens whenever the Chinese Communist Party flips the kill switch. To these critics, if China had a truly open market, Chinese buyers would continue to purchase Western cars en masse, and sales of their models wouldn’t be falling off so dramatically.

Readers either longer memories will recall that American auto manufacturers were similarly disbelieving during the 1970s as the Japanese car industry emerged as a credible competitor in terms of price and especially quality.

Williams spent a week in China as a guest of the Geely Group, along with other international journalists, drove a dozen vehicles, visited the Beijing Auto Show, and talked to Chinese automakers. But his surprise started as he left Shanghai airport—when everything seemed quiet:

Most cars in the pickup area were green-plated “new energy vehicles,” made by brands of all sorts, from BYD or Geely, and even Western brands like Buick and Chevrolet. It’s quite a sight: a nation swept up in an electric car mania, as evidenced by the near-silent crossovers, vans, and sedans aggressively flying over speed bumps while dodging pedestrians headed to rideshare, taxis, or public transportation.

(Zeekr 009. Photo by ‘Navigator84’, via Wikipedia. CC BY-SA 4.0)

The visit included a trip from Shanghai to Geely’s headquarters in Hangzhou, which was spent in the back of a Zeekr 009, a luxury MPV:

The 009 is part of a luxury MPV (minivan) segment that essentially only exists in Asia, and arguably has been perfected by China. Instead of Cadillac Escalades or Lincoln Navigators, black car operators use vehicles like the Buick GL8, Toyota Alphard, Denza D9, Voyah Dreamer, or the Zeekr 009..

The Zeekr 009 is not a cheap van:

It was more than just the ambiance of the 009’s interior, with its tiger wood trim, full Alcantara headliner, real metal finishes brightwork and finishes in the interior, or first-class airline-style middle captain’s chairs that both cooled and massaged me, lulling me to sleep before I knew what happened next. The 009 felt like a low-slung Rolls-Royce with sliding doors, so I understood why it was such a popular option for Chinese businessmen.

But all of the models he experienced were similar:

No matter the price point, they all felt incredibly convincing. They’re high-tech, well-executed machines in ways I hadn’t experienced from European or American manufacturers.

Unlike most Western auto shows there’s not a lot of ‘concept cars’ at the Beijing Auto Show. Chinese visitors prefer to see vehicles that, in theory if not in practice, they could drive away.

I’d later learn that the auto show had more than 100 new model debuts and concepts. That’s a far cry from the Detroit Auto Show last September, which only featured one fully new model. Two other models were refreshed versions of current cars already on sale. None were electric.

In China, the showroom floor was filled to the gills with new electrified models from every single domestic automaker. They all had something to prove, and by god, they were trying. There were hundreds of models on the floor from dozens of brands, most of them just as compelling as what I had seen the day before from Geely.

As to the idea that if China had an open market, they would flock to buy Western brands, Williams concludes that the Western vehicles just aren’t good enough in comparison.

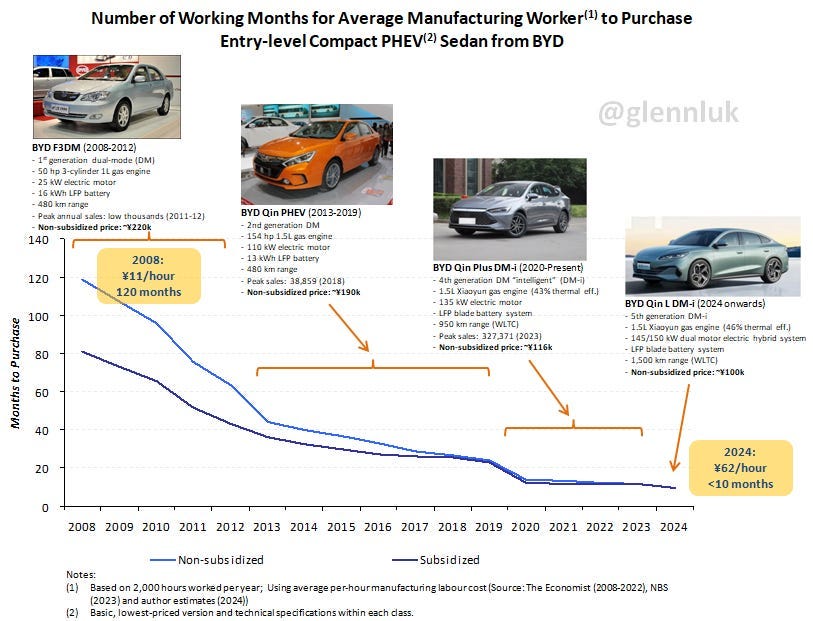

If that’s the qualitative take, there was an interesting chart at Azeem Azhar’s Exponential View a week or so ago, showing the fall in the relative cost of an EV for a Chinese worker over the last two decades. (A significant part of this is down to increasing wages).

(Data: Glenn Luk via Exponential View)

Chinese cost leadership in EVs is already challenging US and German companies. The Tesla Model 2, cancelled in April, was going to cost $25,000 and the cheapest Volkswagen EV is €36,900 – both well above BYD’s $10,000 Seagull. Tariffs of 100% in the US and potentially of at least 50% in the EU are designed to buy time for incumbent carmakers, but the pressure is on to compete.

China registered 8.1 million new EVs last year, and what this chart does say is ‘massive potential home market’. Further, Western tariffs won’t stop Chinese manufacturers exporting to markets in Asia and Brazil. There may also be some consolidation among the hundred or so Chinese EV companies, which may further improve competitiveness.

China took a strategic decision a couple of decades ago to invest in the post-oil economy, and cars are only one part of that: China’s renewables industry is also the world leader. As Exponential View notes,

The lesson is a cautionary tale of hubris, for Western car makers who doubted the exponential trend sweeping electric vehicles and stepped in too timidly and, possibly, too late.

j2t#582

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.