Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. And a reminder that Comments are open, if you want to leave one.

And—have a good weekend!

1: What judges are for

It is the 100th anniversary of the publication of James Joyce’s modernist masterpiece Ulysses this year, which has given Bloomsday—16th June, the day when the action in the novel takes place—an extra zing. (I also wrote about Ulysses here a couple of months ago.)

On his blog, John Naughton, a big Ulysses fan, pointed readers towards the US court judgment in 1933 that ruled that the novel was not pornographic, and could therefore be sold in the US. It took 11 years after the book’s initial publication in Paris before Random House decided to test the legal waters, and there’s a story about that as well. (It was banned in the UK until the 1930s as well).

(‘Ulysses’ judgment, 1933. Public domain).

The publishers of The Little Review, which started serialising Ulysses before publication of the novel, were found guilty on obscenity charges in 1921, fined, and barred from further publication. The relevant copies of the magazine were seized and burned.

In this original trial, the judge prevented certain passages in the book from being read out because there were women in the court—although the only women in the courtroom were Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap, The Little Review’s publishers. Part of the subtext here, of course, is the explicit way in which Joyce writes about female desire, a long-lasting social taboo in Western cultures.

In 1928, the book was added to the list of prohibited obscene books by the United States Customs Court, which made it illegal to bring Ulysses into the country. By 1933, Bennett Cerf of Random House, which owned the US rights, and Morris Ernst, who was the leading American legal authority on obscenity, cooked up a plan to get a copy of the book shipped from Europe and then impounded, so they could go to court.

In fact, US Customs didn’t open the book, even though they had been warned it was on its way. It got sent on to Random House, so Ernst had to take the unopened package back to Customs House and ask them to seize it, before he could go to court.

The judgment, by Judge Woolsey, is an odd piece of writing. Since both the US Government and publisher, Random House, had agreed to waive their right to having the matter decided by a jury, the judge listened to legal arguments and also sat down to read it. He acknowledges that he asked a couple of friends for their thoughts along the way. So, yes, it’s a historic legal judgement. But in places it reads a bit like a book reviewer’s blog post.

"Ulysses" is not an easy book to read or to understand. But there has been much written about it, and in order properly to approach the consideration of it it is advisable to read a number of other books which have now become its satellites. The study of "Ulysses" is, therefore, a heavy task.

The judge nods to the literary reputation that the book had acquired since publication, before he dives into the central legal question of whether the book is pornographic.

But in "Ulysses," in spite of its unusual frankness, I do not detect anywhere the leer of the sensualist. I hold, therefore, that it is not pornographic. In writing "Ulysses," Joyce sought to make a serious experiment in a new, if not wholly novel, literary genre. He takes persons of the lower middle class living in Dublin in 1904 and seeks, not only to describe what they did on a certain day early in June of that year as they went about the city bent on their usual occupations, but also to tell what many of them thought about the while.

And then there’s a striking passage that locates the book in its moment, emerging as a way to write about the world in the years as cinema became mainstream:

What he seeks to get is not unlike the result of a double or, if that is possible, a multiple exposure on a cinema film, which would give a clear foreground with a background visible but somewhat blurred and out of focus in varying degrees. To convey by words an effect which obviously lends itself more appropriately to a graphic technique, accounts, it seems to me, for much of the obscurity which meets a reader of "Ulysses."

A bit later on the judge addresses the problem of the language—“the words”—and of whether they would have an adverse effect on men or women. The prosecutor had replayed The Little Review gambit by declining to read out certain passages because there was “a lady in the courtroom”; Ernst responded that the lady, his wife, was a schoolteacher:

“She’s seen all these words on toilet walls or scribbled on sidewalks by kids who enjoy them because of their being taboo.”

In his judgment Judge Woolsey notes that these are “old Saxon words known to almost all men and, I venture, to many women”, and that they were part of the milieu of the characters that Joyce was writing about. The risk of women being corrupted by literature had a long legal history that still had some decades to play out. In the unsuccessful British obscenity trial of Lady Chatterley’s Lover in the early 1960s, the jury was asked “Would you allow your wife or servants to read it?” Judge Woolsey was impatient with such arguments:

If one does not wish to associate with such folk as Joyce describes, that is one's own choice. In order to avoid indirect contact with them one may not wish to read "Ulysses"; that is quite understandable. But when such a great artist in words, as Joyce undoubtedly is, seeks to draw a true picture of the lower middle class in a European city, ought it to be impossible for the American public legally to see that picture?

There’s also a long account of the court case at the blog of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund.

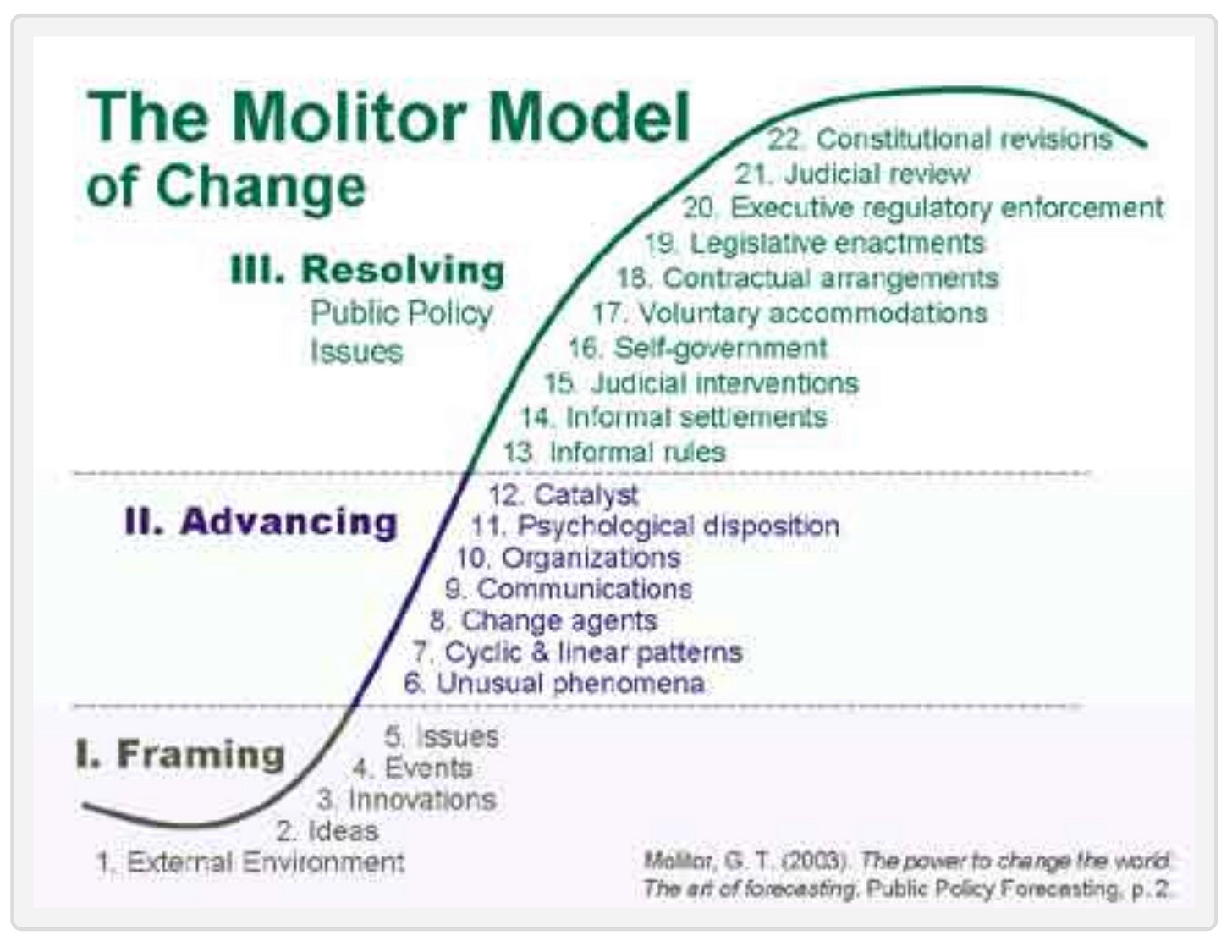

All of this is also a reminder that in Graham Molitor’s S-curve model of policy change, judicial intervention is a sign that an issue is moving into the ‘Resolving’ stage: it has arrived in the area of mainstream discourse.

(The Molitor Model of Change. Diagram via Jay Gary, ChristianFutures.com)

This is one of the reasons, generally, why—as with Ulysses—it often takes several iterations before the law changes its mind; they are a sign of social contestation. One of the reasons why the politicisation of the American courts by the Federalist movement is so disturbing is because judges, and especially the Supreme Court, are now clearly detached from shifts in public opinion. They have abandoned this important social boundary-setting role.

2: How chickens became food

Chickens are ubiquitous now. There are about 80 billion of them worldwide. But they may have been domesticated much later than we had thought. Ann Gibbons has a piece in Science exploring this. The secret to the domestication of the red jungle fowl that chickens are descended from—although we’ve only been certain of which species since 2020–seems to have been the cultivation of rice.

(Red junglefowl, Thailand. Photo by Francesco Veronesi via Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Scientists have also been struggling to identify the dates at which chicken became domesticated: genetics didn’t help, and there wasn’t enough DNA available to narrow it down. Researchers Joris Peters and Greger Larson went back to the archaeological record, and looked at sites across the world

They found the oldest bones of likely chickens came from a site called Ban Non Wat in central Thailand, where farmers grew rice 3250 to 3650 years ago, the team reports today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Farmers buried many skeletons of young members of the genus Gallus as grave goods along with other domesticated animals.

From Thailand the trail headed in one direction to northern China—where chickens appeared about 3,000 years ago—and in the other the Middle East (2,800 years). The first appearance in Europe, at an Etruscan site is at the same time. It took another millennia before chickens reached Britain and northern Europe, transported by the Romans.

There’s also some curious literary evidence for all of this:

“Chickens don’t feature in the Old Testament,” says the study’s lead author Naomi Sykes, an archaeologist at the University of Exeter. “They burst onto the scene in the New Testament.”

Chickens aren’t regarded as a source of food until later on. Initially, they were status symbols,

valued for their feathers, coloring, and loud crow at first light, based on how they were depicted in art and buried as prized grave goods, Sykes says.

But typically, after they arrive in a new part of the world, it takes about 500 years before they stop being prized and become food instead.

There’s still more work to be done, for example to check that the early bones in Thailand are domesticated, and to confirm the link to rice and millet cultivation. But as Sykes says, this is another story about how humans relate to the non-human world:

“This isn’t just about chickens or rice... How humans relate to chickens is a brilliant lens to understand how humans relate to the natural world.”

Update

I wrote about Davos and the World Economic Forum here recently. Izabella Kaminska had a long and entertaining piece about Davos on her Blindspot newsletter, and in front of her paywall, that moves through memoir and reflection by turn. Here’s an extract:

Despite going since at least the 1970s — WEF suddenly caught the attention of conspiracy theory circles. And in the most amazing way…The irony, in my opinion, was that despite Schwab’s books being literally given out for free in Forum goodie bags, I had met few of the “global elite” who had actually ever read them…

My take on Davos, to the contrary, had always been that despite desperately trying to be relevant and ahead of the curve, the power elite usually proved via the WEF phenomenon that they were the exact opposite... That’s because the feedback always came too late.

j2t#332

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.