17 February 2022. Mobility | Sports

We need new measurements of mobility. It’s time for football clubs to be about more than football.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

1: We need a new measure of mobility

There’s an emerging market for ‘micromobility’, especially in cities—sometimes called lightweight transport. (It’s always a sign of a still emerging market when the language to describe it hasn’t stabilised). Anyway, think of e-bikes and scooters as examples.

Thanks to the Exponential View newsletter, I found a couple of fascinating posts on this from Horace Dediu, who specialises in this area.

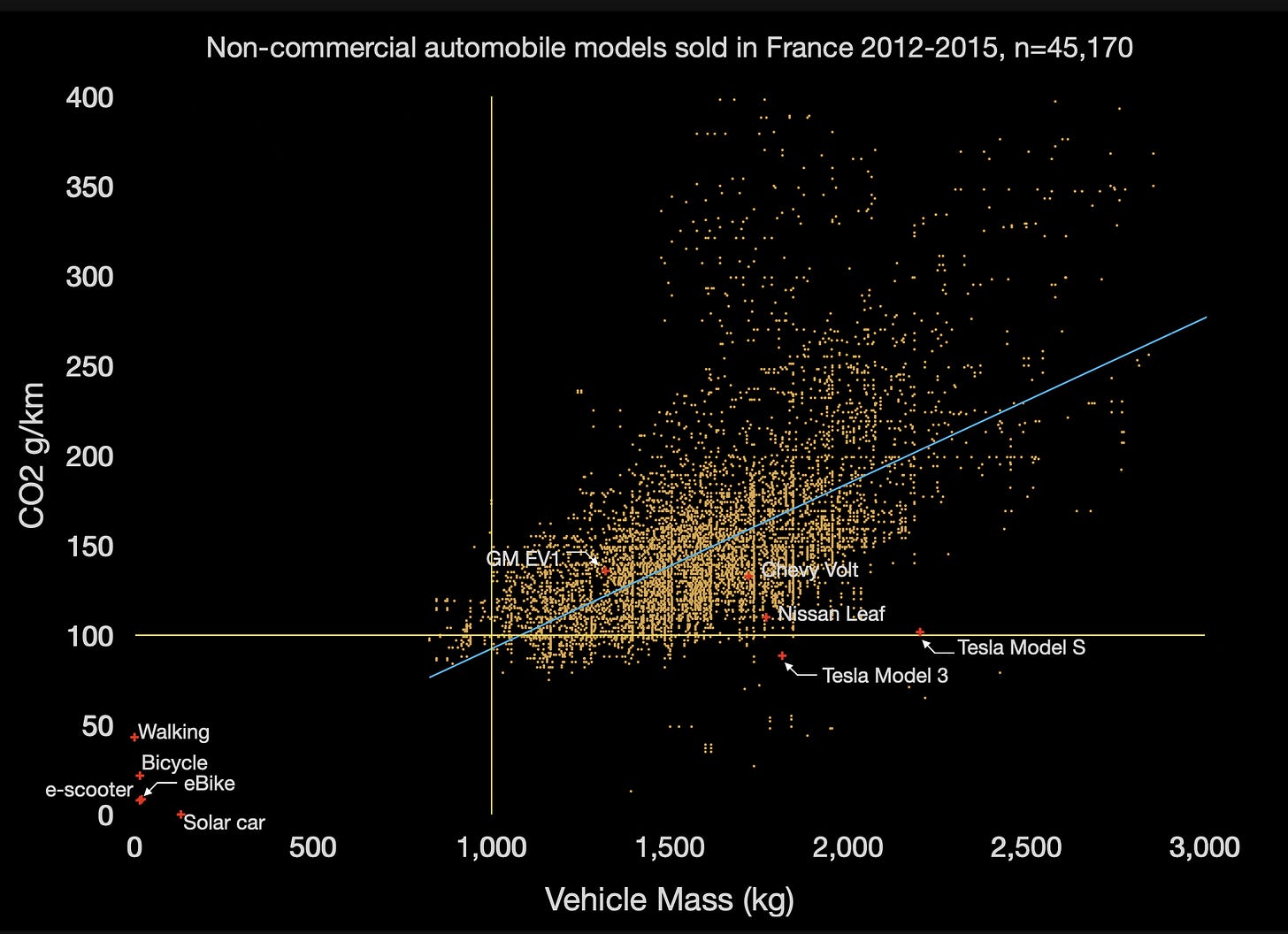

His business, Micromobility Industries, focuses on vehicles that weigh in (literally) at less than 500kg, and the reason he does this is because cars are getting heavier and there’s a direct relationship between weight and carbon emissions.

This data is a little old, and is just from France, but I doubt it’s changed that much or varies much by country. The gap between the car market (that huge blob to the right) and the micro-market (at the bottom left) is striking. And no—electric vehicles won’t do that much to all of this, because of their embodied emissions.

(Source: Micromobility Industries)

They chose the 500kg threshold because:

Our mission at Micromobility Industries has always been to shine a light on this sub-auto world, the negative space in the graph of personal automobiles. This is why micromobility is defined not as what it is but what it isn’t. I chose a weight threshold because I knew what would not fit there, and in so doing, I knew how many other things would. It’s a "no-man’s land" but yet it is teeming with other species. You don’t need a telescope. If you choose to look with a microscope you can see entire new worlds.

Incidentally, 500kg is an interesting weight. I looked up the cars that came in at around that, and most of them are from the 1950s and the 1960s—including the star of The Italian Job.

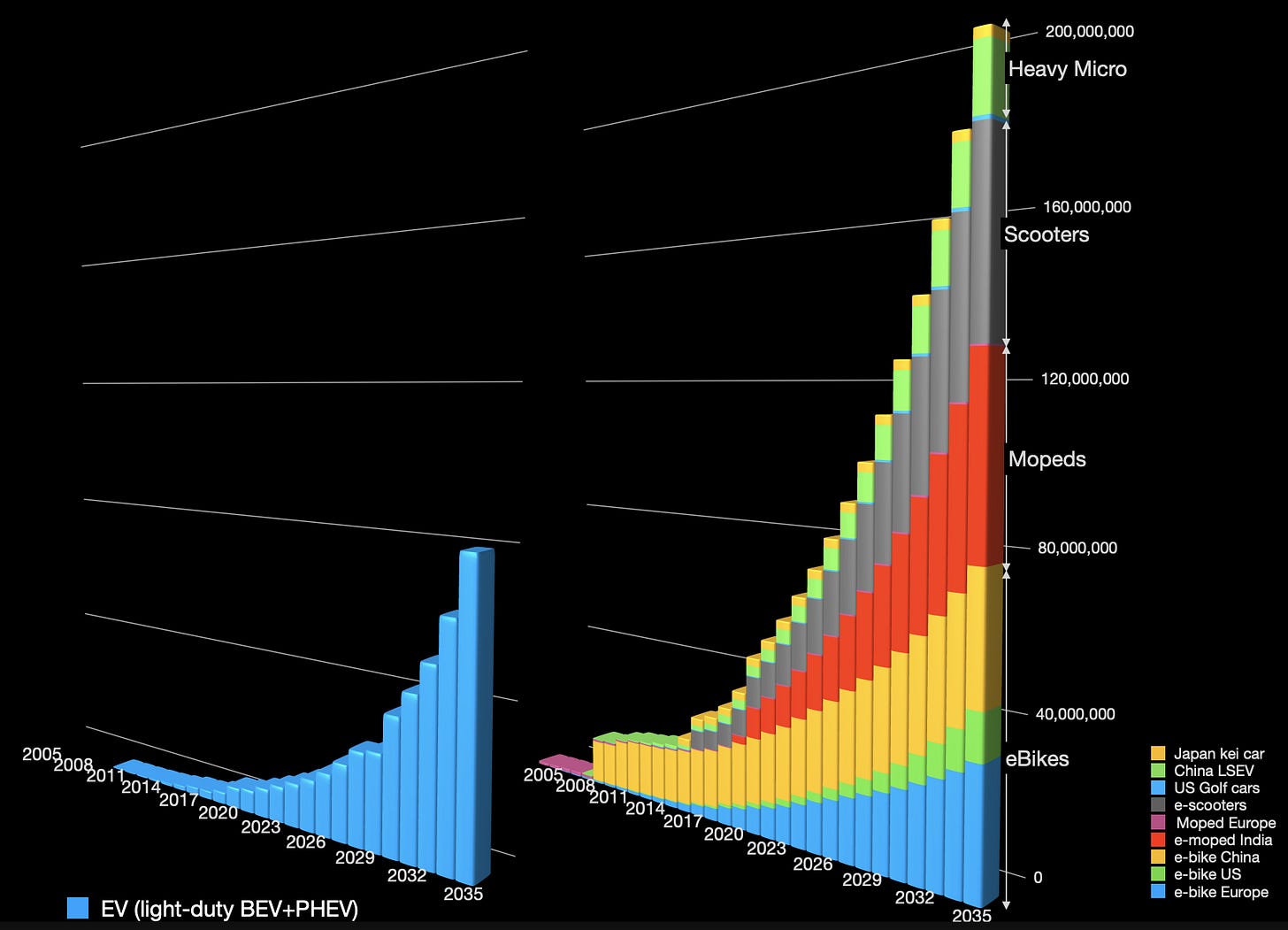

The other reason they look at this micromobility sector is because it’s potentially much larger than the car sector, at least by volume.

The chart (below) extrapolates from the data we do have: The growth in the European (EU) e-bike market. It takes into consideration the e-scooter and e-moped and some of the heavy micromobility (kei car and golf car(t)). It considers the electric two-wheeled market in India, which promises to grow rapidly through disruptive new entries. It adds up to hundreds of millions of units of production. Over 1.2 billion in 15 years. Enough to supply mobility to a rapidly emerging, personally mobile, non-consuming middle class and an automobility over-served existing urban citizenry. And this is over a 15 year period: three automobile product cycles.

—

(Source: Micromobility Industries)

This is all interesting enough, but in a more recent post Dediu also suggests a policy implication. He says we need a new measure of mobility:

when the power and range of the vehicle is irrelevant (as is the case with micromobility devices), we need a new metric. 150 to 400 horsepower is necessary (maybe) to move a 3000lb vehicle, but it’s far more than what is necessary to move a person, a product, or a meal. And moving people, products, and meals is what micromobility is for. And fortunately for the climate, it is an efficient method of moving these things.

His proposal is for a new unit of measurement: ‘the modicum of transport’.

The yardstick of performance for micro vehicles should be different. It should be centered not on the vehicle but on the passenger. As such, I propose a new yardstick metric which I call the MOT... It is defined as 1MOT = 0.1kWh/kgkm (or 10kWh/100kg km). Plural is “MOTz.” It’s the nominal energy cost of transporting one person one kilometer. ... Note that MOT is not a “Minimum of Transport.” A modicum is a small quantity of something desirable.

The purpose is to identify in a meaningful way the utility of a mode of transport. And there’s data. All of the micromobility modes come in at around 1 MOT. And, of course, the car is off the scale:

(Source: Micromobility Industries)

I shared this earlier with the team I typically work with on transport futures. One of them, Anna Rothnie, replied that using what we need is ‘one of the very definitions of sustainability’”. Exactly. Or juste, as Horace Dediu might put it.

2: It’s time for football clubs to be about a bit more than football

I support Sunderland football team, although I’m not going to dwell on that private grief longer than it takes to say that the team has been languishing in one of the lower tiers of English football for three years and has also had a completely chaotic couple of weeks recently.

But one of the benefits of this chaos is that I was reminded of an interesting article from just before Christmas about what a club would look like if it was fully engaged in its community.

It’s written by Mark Bradley of The Fan Experience Company, and although he’s another long-suffering Sunderland fan, it’s based on his work with clubs across Europe:

Our work aims to help clubs (any level, men’s or women’s) to grow sustainably: (to) prosper regardless of what happens on the pitch. Since Ana and I started the business in 2005, we’ve worked across Europe and Asia, from Tallinn to Tilburg and from Llanelli to Yerevan... By far and away the most important ingredient is the purpose of the club we’re working with. What are they for? What difference do they make? Why would the local community suffer if they weren’t there? What do they give (back)?

Because football clubs are distinctive institutions. They have deep roots into their communities, even when they regard those transactionally. They can do a whole lot more than they do. In the piece, Bradley talks, for example, about the Irish club Bohemians, based in a tough area of Dublin, which “has re-purposed itself from a football club to a community support hub”:

When the people of Ireland got a chance to change the law to give women the right to choose, Bohs campaigned for a ‘yes’ vote. In this country, we’ve just seen the right to protest quietly criminalised... I don’t see any high-profile football clubs pointing this out. Over consecutive years Bohs’ third kit has first supported refugee charities (with ‘Refugees are Welcome’ on the shirt) and more recently, it has borne the name of local indie band Fontaines DC, who are helping the club to raise awareness of homelessness and the damage it does to people.

—

(A Dublin bus kitted out in Bohemians colours, 2020. Photo Cityswift Ireland/flickr, CC BT 2.0)

Similarly, Lewes FC, which is owned by its fans, stands out for its commitment to equality and inclusion, and pays its women’s and men’s teams the same salary. The women are in the second tier of women’s football, competing with teams backed by professional clubs. The men, well, not so much. As with Bohemians, though, their commitment means that they have members across the world—even from people who are unlikely ever to get to a match.

He has other examples as well; the Danish club Nordsjælland, which has a ‘Right to Dream’ academy and where all staff donate 1% of their wages to charities. Or Bury FC, being rebuilt after bankruptcy, which has “the higher purpose of making lives better”—both growing the club and supporting their community. They have an active network of volunteers.

Sunderland, as it happens, has a Foundation—the Foundation of Light—that is engaged in its community—for example by actively supporting the Sunderland Community Soup Kitchen. The Foundation is chaired by Sir Bob Murray, the last Sunderland AFC chairman to be brought up in the area.

Bradley has a simple suggestion: that instead of the Foundation being an offshoot of the club, the club should be an offshoot of the Foundation. This would, literally, place the football team at the heart of the community:

In my experience, fans usually have an intrinsic understanding of their clubs’ values, whereas most owners don’t have the first clue. We have had more CEOs than 1-1 draws in recent times (and there’ve been a lot of the latter), but if you have a clear vision of what the point of the club is, the CEO becomes the latest ‘steward’ of the Light, reinforcing values, finding new ways to make lives better, putting our club on the map for more than just misfiring football.

Fiascos like the failed breakaway European Super League show how far football has moved away from its communities. As I wrote at the time, it showed the split between (borrowing Jane Jacobs’ distinction) the financially footloose ‘traders’ who mostly own the parts of the game that make any money and the ‘guardians’ of the supporters’ clubs.

Let’s face it, there’s something slightly strange about a Manchester United opportunistically laden with private equity style debt and its player Marcus Rashford standing up for—and donating to—the kinds of communities he grew up.

For me Bradley’s piece suggests a way to reconnect the two. It’s about time that football clubs were famous for a bit more than football.

——————————-

j2t#264

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.